|

| HOME | SUMMA | PRAYERS | FATHERS | CLASSICS | CONTACT |

| CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| CATHOLIC SAINTS INDEX | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| CATHOLIC DICTIONARY | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

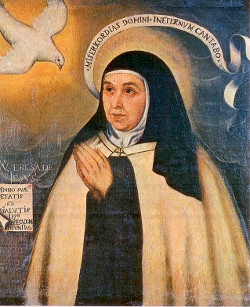

The Life of St. Teresa of JesusChapter XXXV -The Foundation of the House of St. Joseph. The Observation of Holy Poverty Therein. How the Saint Left Toledo.

1. When I was staying with this lady, [1] already spoken of, in whose house I remained more than six months, our Lord ordained that a holy woman [2] of our Order should hear of me, who was more than seventy leagues away from the place. She happened to travel this way, and went some leagues out of her road that she might see me. Our Lord had moved her in the same year, and in the same month of the year, that He had moved me, to found another monastery of the Order; and as He had given her this desire, she sold all she possessed, and went to Rome to obtain the necessary faculties. She went on foot, and barefooted. She is a woman of great penance and prayer, and one to whom our Lord gave many graces; and our Lady appeared to her, and commanded her to undertake this work. Her progress in the service of our Lord was so much greater than mine, that I was ashamed to stand in her presence. She showed me Briefs she brought from Rome, and during the fortnight she remained with me we laid our plan for the founding of these monasteries.

2. Until I spoke to her, I never knew that our rule, before it was mitigated, required of us that we should possess nothing; [3] nor was I going to found a monastery without revenue, [4] for my intention was that we should be without anxiety about all that was necessary for us, and I did not think of the many anxieties which the possession of property brings in its train. This holy woman, taught of our Lord, perfectly understood−−though she could not read−−what I was ignorant of, notwithstanding my having read the Constitutions [5] so often; and when she told me of it, I thought it right, though I feared they would never consent to this, but would tell me I was committing follies, and that I ought not to do anything whereby I might bring suffering upon others. If this concerned only myself, nothing should have kept me back,−−on the contrary, it would have been my great joy to think that I was observing the counsels of Christ our Lord; for His Majesty had already given me great longings for poverty. [6]

3. As for myself, I never doubted that this was the better part; for I had now for some time wished it were possible in my state to go about begging, for the love of God−−to have no house of my own, nor anything else. But I was afraid that others−−if our Lord did not give them the same desire−−might live in discontent. Moreover, I feared that it might be the cause of some distraction: for I knew some poor monasteries not very recollected, and I did not consider that their not being recollected was the cause of their poverty, and that their poverty was not the cause of their distraction: distraction never makes people richer, and God never fails those who serve Him. In short, I was weak in faith; but not so this servant of God.

4. As I took the advice of many in everything, I found scarcely any one of this opinion−−neither my confessor, nor the learned men to whom I spoke of it. They gave me so many reasons the other way, that I did not know what to do. But when I saw what the rule required, and that poverty was the more perfect way, I could not persuade myself to allow an endowment. And though they did persuade me now and then that they were right, yet, when I returned to my prayer, and saw Christ on the cross, so poor and destitute, I could not bear to be rich, and I implored Him with tears so to order matters that I might be poor as He was.

5. I found that so many inconveniences resulted from an endowment, and saw that it was the cause of so much trouble, and even distraction, that I did nothing but dispute with the learned. I wrote to that Dominican friar [7] who was helping us, and he sent back two sheets by way of reply, full of objections and theology against my plan, telling me that he had thought much on the subject. I answered that, in order to escape from my vocation, the vow of poverty I had made, and the perfect observance of the counsels of Christ, I did not want any theology to help me, and in this case I should not thank him for his learning. If I found any one who would help me, it pleased me much. The lady in whose house I was staying was a great help to me in this matter. Some at first told me that they agreed with me; afterwards, when they had considered the matter longer, they found in it so many inconveniences that they insisted on my giving it up. I told them that, though they changed their opinion so quickly, I would abide by the first.

6. At this time, because of my entreaties,−−for the lady had never seen the holy friar, Peter of Alcantara,−−it pleased our Lord to bring him to her house. As he was a great lover of poverty, and had lived in it for so many years, he knew well the treasures it contains, and so he was a great help to me; he charged me on no account whatever to give up my purpose. Now, having this opinion and sanction,−−no one was better able to give it, because he knew what it was by long experience,−−I made up my mind to seek no further advice.

7. One day, when I was very earnestly commending the matter to God, our Lord told me that I must by no means give up my purpose of founding the monastery in poverty; it was His will, and the will of His Father: He would help me. I was in a trance; and the effects were such, that I could have no doubt it came from God. On another occasion, He said to me that endowments bred confusion, with other things in praise of poverty; and assured me that whosoever served Him would never be in want of the necessary means of living: and this want, as I have said, [8] I never feared myself. Our Lord changed the dispositions also of the licentiate,−−I am speaking of the Dominican friar, [9]−−who, as I said, wrote to me that I should not found the monastery without an endowment. Now, I was in the greatest joy at hearing this; and having these opinions in my favour, it seemed to me nothing less than the possession of all the wealth of the world, when I had resolved to live in poverty for the love of God.

8. At this time, my Provincial withdrew the order and the obedience, in virtue of which I was staying in that house. [10] He left it to me to do as I liked: if I wished to return I might do so; if I wished to remain I might also do so for a certain time. But during that time the elections in my monastery [11] would take place and I was told that many of the nuns wished to lay on me the burden of superiorship. The very thought of this alone was a great torment to me; for though I was resolved to undergo readily any kind of martyrdom for God, I could not persuade myself at all to accept this; for, putting aside the great trouble it involved,−−because the nuns were so many,−−and other reasons, such as that I never wished for it, nor for any other office,−−on the contrary, had always refused them,−−it seemed to me that my conscience would be in great danger; and so I praised God that I was not then in my convent. I wrote to my friends and asked them not to vote for me.

9. When I was rejoicing that I was not in that trouble, our Lord said to me that I was on no account to keep away; that as I longed for a cross, there was one ready for me, and that a heavy one: that I was not to throw it away, but go on with resolution; He would help me, and I must go at once. I was very much distressed, and did nothing but weep, because I thought that my cross was to be the office of prioress; and, as I have just said, I could not persuade myself that it would be at all good for my soul−−nor could I see any means by which it would be. I told my confessor of it, and he commanded me to return at once: that to do so was clearly the most perfect way; and that, because the heat was very great,−−it would be enough if I arrived before the election,−−I might wait a few days, in order that my journey might do me no harm.

10. But our Lord had ordered it otherwise. I had to go at once, because the uneasiness I felt was very great; and I was unable to pray, and thought I was failing in obedience to the commandments of our Lord, and that as I was happy and contented where I was, I would not go to meet trouble. All my service of God there was lip−service: why did I, having the opportunity of living in greater perfection, neglect it? If I died on the road, let me die. Besides, my soul was in great straits, and our Lord had taken from me all sweetness in prayer. In short, I was in such a state of torment, that I begged the lady to let me go; for my confessor, when he saw the plight I was in, had already told me to go, God having moved him as He had moved me. The lady felt my departure very much, and that was another pain to bear; for it had cost her much trouble, and diverse importunities of the Provincial, to have me in her house.

11. I considered it a very great thing for her to have given her consent, when she felt it so much; but, as she was a person who feared God exceedingly,−−and as I told her, among many other reasons, that my going away tended greatly to His service, and held out the hope that I might possibly return,−−she gave way, but with much sorrow. I was now not sorry myself at coming away, for I knew that it was an act of greater perfection, and for the service of God. So the pleasure I had in pleasing God took away the pain of quitting that lady,−−whom I saw suffering so keenly,−−and others to whom I owed much, particularly my confessor of the Society of Jesus, in whom I found all I needed. But the greater the consolations I lost for our Lord's sake, the greater was my joy in losing them. I could not understand it, for I had a clear consciousness of these two contrary feelings−−pleasure, consolation, and joy in that which weighed down my soul with sadness. I was joyful and tranquil, and had opportunities of spending many hours in prayer; and I saw that I was going to throw myself into a fire; for our Lord had already told me that I was going to carry a heavy cross,−−though I never thought it would be so heavy as I afterwards found it to be,−−yet I went forth rejoicing. I was distressed because I had not already begun the fight, since it was our Lord's will that I should be in it. Thus His Majesty gave me strength, and established it in my weakness. [12]

12. As I have just said, I could not understand how this could be. I thought of this illustration: if I were possessed of a jewel, or any other thing which gave me great pleasure, and it came to my knowledge that a person whom I loved more than myself, and whose satisfaction I preferred to my own, wished to have it, it would give me great pleasure to deprive myself of it, because I would give all I possessed to please that person. Now, as the pleasure of giving pleasure to that person surpasses any pleasure I have in that jewel myself, I should not be distressed in giving away that or anything else I loved, nor at the loss of that pleasure which the possession of it gave me. So now, though I wished to feel some distress when I saw that those whom I was leaving felt my going so much, yet, notwithstanding my naturally grateful disposition,−−which, under other circumstances, would have been enough to have caused me great pain,−−at this time, though I wished to feel it, I could feel none.

13. The delay of another day was so serious a matter in the affairs of this holy house, that I know not how they would have been settled if I had waited. Oh, God is great! I am often lost in wonder when I consider and see the special help which His Majesty gave me towards the establishment of this little cell of God,−−for such I believe it to be,−−the lodging wherein His Majesty delights; for once, when I was in prayer, He told me that this house was the paradise of his delight. [13] It seems, then, that His Majesty has chosen these whom he has drawn hither, among whom I am living very much ashamed of myself. [14] I could not have even wished for souls such as they are for the purpose of this house, where enclosure, poverty, and prayer are so strictly observed; they submit with so much joy and contentment, that every one of them thinks herself unworthy of the grace of being received into it,−−some of them particularly; for our Lord has called them out of the vanity and dissipation of the world, in which, according to its laws, they might have lived contented. Our Lord has multiplied their joy, so that they see clearly how He had given them a hundredfold for the one thing they have left, [15] and for which they cannot thank His Majesty enough. Others He has advanced from well to better. To the young He gives courage and knowledge, so that they may desire nothing else, and also to understand that to live away from all things in this life is to live in greater peace even here below. To those who are no longer young, and whose health is weak, He gives−−and has given−−the strength to undergo the same austerities and penance with all the others.

14. O my Lord! how Thou dost show Thy power! There is no need to seek reasons for Thy will; for with Thee, against all natural reason, all things are possible: so that thou teachest clearly there is no need of anything but of loving Thee [16] in earnest, and really giving up everything for Thee, in order that Thou, O my Lord, might make everything easy. It is well said that Thou feignest to make Thy law difficult: [17] I do not see it, nor do I feel that the way that leadeth unto Thee is narrow. I see it as a royal road, and not a pathway; a road upon which whosoever really enters, travels most securely. No mountain passes and no cliffs are near it: these are the occasions of sin. I call that a pass,−−a dangerous pass,−−and a narrow road, which has on one side a deep hollow, into which one stumbles, and on the other a precipice, over which they who are careless fall, and are dashed to pieces. He who loves Thee, O my God, travels safely by the open and royal road, far away from the precipice: he has scarcely stumbled at all, when Thou stretchest forth Thy hand to save him. One fall−−yea, many falls−−if he does but love Thee, and not the things of the world, are not enough to make him perish; he travels in the valley of humility. I cannot understand what it is that makes men afraid of the way of perfection.

15. May our Lord of His mercy make us see what a poor security we have in the midst of dangers so manifest, when we live like the rest of the world; and that true security consists in striving to advance in the way of God! Let us fix our eyes upon Him, and have no fear that the Sun of justice will ever set, or suffer us to travel to our ruin by night, unless we first look away from Him. People are not afraid of living in the midst of lions, every one of whom seems eager to tear them: I am speaking of honours, pleasures, and the like joys, as the world calls them: and herein the devil seems to make us afraid of ghosts. I am astonished a thousand times, and ten thousand times would I relieve myself by weeping, and proclaim aloud my own great blindness and wickedness, if, perchance, it might help in some measure to open their eyes. May He, who is almighty, of His goodness open their eyes, and never suffer mine to be blind again!

|

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved