|

| HOME | SUMMA | PRAYERS | FATHERS | CLASSICS | CONTACT |

| CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| CATHOLIC SAINTS INDEX | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| CATHOLIC DICTIONARY | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

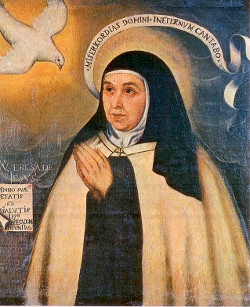

The Life of St. Teresa of JesusChapter XXXIII -The Foundation of the Monastery Hindered. Our Lord Consoles the Saint.

1. When the matter was in this state−−so near its conclusion, that on the very next day the papers were to be signed−−then it was that the Father Provincial changed his mind. I believe that the change was divinely ordered−−so it appeared afterwards; for while so many prayers were made, our Lord was perfecting His work and arranging its execution in another way. When the Provincial refused us, my confessor bade me forthwith to think no more of it, notwithstanding the great trouble and distress which our Lord knows it cost me to bring it to this state. When the work was given up and abandoned, people were the more convinced that it was altogether the foolishness of women; and the complaints against me were multiplied, although I had until then this commandment of my Provincial to justify me.

2. I was now very much disliked throughout the whole monastery, because I wished to found another with stricter enclosure. It was said I insulted my sisters; that I could serve God among them as well as elsewhere, for there were many among them much better than I; that I did not love the house, and that it would have been better if I had procured greater resources for it than for another. Some said I ought to be put in prison; others−−but they were not many−−defended me in some degree. I saw well enough that they were for the most part right, and now and then I made excuses for myself; though, as I could not tell them the chief reason, which was the commandment of our Lord, I knew not what to do, and so was silent.

3. In other respects God was most merciful unto me, for all this caused me no uneasiness; and I gave up our design with much readiness and joy, as if it cost me nothing. No one could believe it, not even those men of prayer with whom I conversed; for they thought I was exceedingly pained and sorry: even my confessor himself could hardly believe it. I had done, as it seemed to me, all that was in my power. I thought myself obliged to do no more than I had done to fulfil our Lord's commandment, and so I remained in the house where I was, exceedingly happy and joyful; though, at the same time, I was never able to give up my conviction that the work would be done. I had now no means of doing it, nor did I know how or when it would be done; but I firmly believed in its accomplishment.

4. I was much distressed at one time by a letter which my confessor wrote to me, as if I had done anything in the matter contrary to his will. Our Lord also must have meant that suffering should not fail me there where I should feel it most; and so, amid the multitude of my persecutions, when, as it seemed to me, consolations should have come from my confessor, he told me that I ought to recognise in the result that all was a dream; that I ought to lead a new life by ceasing to have anything to do for the future with it, or even to speak of it any more, seeing the scandal it had occasioned. He made some further remarks, all of them very painful. This was a greater affliction to me than all the others together. I considered whether I had done anything myself, and whether I was to blame for anything that was an offence unto God; whether all my visions were illusions, all my prayers a delusion, and I, therefore, deeply deluded and lost. This pressed so heavily upon me, that I was altogether disturbed and most grievously distressed. But our Lord, who never failed me in all the trials I speak of, so frequently consoled and strengthened me, that I need not speak of it here. He told me then not to distress myself; that I had pleased God greatly, and had not sinned against Him throughout the whole affair; that I was to do what my confessors required of me, and be silent on the subject till the time came to resume it. I was so comforted and so happy, that the persecution which had befallen me seemed to be as nothing at all.

5. Our Lord now showed me what an exceedingly great blessing it is to be tried and persecuted for His sake; for the growth of the love of God in my soul, which I now discerned, as well as of many other virtues, was such as to fill me with wonder. It made me unable to abstain from desiring trials, and yet those about me thought I was exceedingly disheartened; and I must have been so, if our Lord in that extremity had not succoured me with His great compassion. Now was the beginning of those more violent impetuosities of the love of God of which I have spoken before, [1] as well as of those profounder trances. I kept silence, however, and never spoke of those graces to any one. The saintly Dominican [2] was as confident as I was that the work would be done; and as I would not speak of it, in order that nothing might take place contrary to the obedience I owed my confessor, he communicated with my companion, and they wrote letters to Rome and made their preparations.

6. Satan also contrived now that persons should hear one from another that I had had a revelation in the matter; and people came to me in great terror, saying that the times were dangerous, that something might be laid to my charge, and that I might be taken before the Inquisitors. I heard this with pleasure, and it made me laugh, because I never was afraid of them; for I knew well enough that in matters of faith I would not break the least ceremony of the Church, that I would expose myself to die a thousand times rather than that any one should see me go against it or against any truth of Holy Writ. So I told them I was not afraid of that, for my soul must be in a very bad state if there was anything the matter with it of such a nature as to make me fear the Inquisition; I would go myself and give myself up, if I thought there was anything amiss; and if I should be denounced, our Lord would deliver me, and I should gain much.

7. I had recourse to my Dominican father; for I could rely upon him, because he was a learned man. I told him all about my visions, my way of prayer, the great graces our Lord had given me, as clearly as I could, and I begged him to consider the matter well, and tell me if there was anything therein at variance with the Holy Writings, and give me his opinion on the whole matter. He reassured me much, and, I think, profited himself; for though he was exceedingly good, yet, from this time forth, he gave himself more and more to prayer, and retired to a monastery of his Order which was very lonely, that he might apply himself more effectually to prayer, where he remained more than two years. He was dragged out of his solitude by obedience, to his great sorrow: his superiors required his services; for he was a man of great ability. I, too, on my part, felt his retirement very much, because it was a great loss to me, though I did not disturb him. But I knew it was a gain to him; for when I was so much distressed at his departure, our Lord bade me be comforted, not to take it to heart, for he was gone under good guidance.

8. So, when he came back, his soul had made such great progress, and he was so advanced in the ways of the spirit, that he told me on his return he would not have missed that journey for anything in the world. And I, too, could say the same thing; for where he reassured and consoled me formerly by his mere learning, he did so now through that spiritual experience he had gained of supernatural things. And God, too, brought him here in time; for He saw that his help would be required in the foundation of the monastery, which His Majesty willed should be laid.

9. I remained quiet after this for five or six months, neither thinking nor speaking of the matter; nor did our Lord once speak to me about it. I know not why, but I could never rid myself of the thought that the monastery would be founded. At the end of that time, the then Rector [3] of the Society of Jesus having gone away, His Majesty brought into his place another, [4] of great spirituality, high courage, strong understanding, and profound learning, at the very time when I was in great straits. As he who then heard my confession had a superior over him−−the fathers of the Society are extremely strict about the virtue of obedience and never stir but in conformity with the will of their superiors,−−so he would not dare, though he perfectly understood my spirit, and desired the accomplishment of my purpose, to come to any resolution; and he had many reasons to justify his conduct. I was at the same time subject to such great impetuosities of spirit, that I felt my chains extremely heavy; nevertheless, I never swerved from the commandment he gave me.

10. One day, when in great distress, because I thought my confessor did not trust me, our Lord said to me, Be not troubled; this suffering will soon be over. I was very much delighted, thinking I should die shortly; and I was very happy whenever I recalled those words to remembrance. Afterwards I saw clearly that they referred to the coming of the rector of whom I am speaking, for never again had I any reason to be distressed. The rector that came never interfered with the father−minister who was my confessor. On the contrary, he told him to console me,−−that there was nothing to be afraid of,−−and not to direct me along a road so narrow, but to leave the operations of the Spirit of God alone; for now and then it seemed as if these great impetuosities of the spirit took away the very breath of the soul.

11. The rector came to see me, and my confessor bade me speak to him in all freedom and openness. I used to feel the very greatest repugnance to speak of this matter; but so it was, when I went into the confessional, I felt in my soul something, I know not what. I do not remember to have felt so either before or after towards any one. I cannot tell what it was, nor do I know of anything with which I could compare it. It was a spiritual joy, and a conviction in my soul that his soul must understand mine, that it was in unison with it, and yet, as I have said, I knew not how. If I had ever spoken to him, or had heard great things of him, it would have been nothing out of the way that I should rejoice in the conviction that he would understand me; but he had never spoken to me before, nor I to him, and, indeed, he was a person of whom I had no previous knowledge whatever.

12. Afterwards, I saw clearly that my spirit was not deceived; for my relations with him were in every way of the utmost service to me and my soul, because his method of direction is proper for those persons whom our Lord seems to have led far on the way, seeing that He makes them run, and not to crawl step by step. His plan is to render them thoroughly detached and mortified, and our Lord has endowed him with the highest gifts herein as well as in many other things beside. As soon as I began to have to do with him, I knew his method at once, and saw that he had a pure and holy soul, with a special grace of our Lord for the discernment of spirits. He gave me great consolation. Shortly after I had begun to speak to him, our Lord began to constrain me to return to the affair of the monastery, and to lay before my confessor and the father−rector many reasons and considerations why they should not stand in my way. Some of these reasons made them afraid, for the father−rector never had a doubt of its being the work of the Spirit of God, because he regarded the fruits of it with great care and attention. At last, after much consideration, they did not dare to hinder me. [5]

13. My confessor gave me leave to prosecute the work with all my might. I saw well enough the trouble I exposed myself to, for I was utterly alone, and able to do so very little. We agreed that it should be carried on with the utmost secrecy; and so I contrived that one of my sisters, [6] who lived out of the town, should buy a house, and prepare it as if for herself, with money which our Lord provided for us. [7] I made it a great point to do nothing against obedience; but I knew that if I spoke of it to my superiors all was lost, as on the former occasion, and worse even might happen. In holding the money, in finding the house, in treating for it, in putting it in order, I had so much to suffer; and, for the most part, I had to suffer alone, though my friend did what she could: she could do but little, and that was almost nothing. Beyond giving her name and her countenance, the whole of the trouble was mine; and that fell upon me in so many ways, that I am astonished now how I could have borne it. [8] Sometimes, in my affliction, I used to say: O my Lord, how is it that Thou commandest me to do that which seems impossible?−−for, though I am a woman, yet, if I were free, it might be done; but when I am tied in so many ways, without money, or the means of procuring it, either for the purpose of the Brief or for any other,−−what, O Lord, can I do?

14. Once when I was in one of my difficulties, not knowing what to do, unable to pay the workmen, St. Joseph, my true father and lord, appeared to me, and gave me to understand that money would not be wanting, and I must hire the workmen. So I did, though I was penniless; and our Lord, in a way that filled those who heard of it with wonder, provided for me. The house offered me was too small,−−so much so, that it seemed as if it could never be made into a monastery,−−and I wished to buy another, but had not the means, and there was neither way nor means to do so. I knew not what to do. There was another little house close to the one we had, which might have formed a small church. One day, after Communion, our Lord said to me, I have already bidden thee to go in anyhow. And then, as if exclaiming, said: Oh, covetousness of the human race, thinking that even the whole earth is too little for it! how often have I slept in the open air, because I had no place to shelter Me! [9] I was alarmed, and saw that He had good reasons to complain. I went to the little house, arranged the divisions of it, and found that it would make a sufficient, though small, monastery. I did not care now to add to the site by purchase, and so I did nothing but contrive to have it prepared in such a way that it could be lived in. Everything was coarse, and nothing more was done to it than to render it not hurtful to health−−and that must be done everywhere.

15. As I was going to Communion on her feast, St. Clare appeared to me in great beauty, and bade me take courage, and go on with what I had begun; she would help me. I began to have a great devotion to St. Clare; and she has so truly kept her word, that a monastery of nuns of her Order in our neighbourhood helped us to live; and, what is of more importance, by little and little she so perfectly fulfilled my desire, that the poverty which the blessed Saint observes in her own house is observed in this, and we are living on alms. It cost me no small labour to have this matter settled by the plenary sanction and authority of the Holy Father, [10] so that it shall never be otherwise, and we possess no revenues. Our Lord is doing more for us−−perhaps we owe it to the prayers of this blessed Saint; for, without our asking anybody, His Majesty supplies most abundantly all our wants. May He be blessed for ever! Amen.

16. On one of these days−−it was the Feast of the Assumption of our Lady−−I was in the church of the monastery of the Order of the glorious St. Dominic, thinking of the events of my wretched life, and of the many sins which in times past I had confessed in that house. I fell into so profound a trance, that I was as it were beside myself. I sat down, and it seemed as if I could neither see the Elevation nor hear Mass. This afterwards became a scruple to me. I thought then, when I was in that state, that I saw myself clothed with a garment of excessive whiteness and splendour. At first I did not see who was putting it on me. Afterwards I saw our Lady on my right hand, and my father St. Joseph on my left, clothing me with that garment. I was given to understand that I was then cleansed from my sins. When I had been thus clad−−I was filled with the utmost delight and joy−−our Lady seemed at once to take me by both hands. She said that I pleased her very much by being devout to the glorious St. Joseph; that I might rely on it my desires about the monastery were accomplished, and that our Lord and they too would be greatly honoured in it; that I was to be afraid of no failure whatever, though the obedience under which it would be placed might not be according to my mind, because they would watch over us, and because her Son had promised to be with us [11]−−and, as a proof of this, she would give me that jewel. She then seemed to throw around my neck a most splendid necklace of gold, from which hung a cross of great value. The stones and gold were so different from any in this world, that there is nothing wherewith to compare them. The beauty of them is such as can be conceived by no imagination,−−and no understanding can find out the materials of the robe, nor picture to itself the splendours which our Lord revealed, in comparison with which all the splendours of earth, so to say, are a daubing of soot. This beauty, which I saw in our Lady, was exceedingly grand, though I did not trace it in any particular feature, but rather in the whole form of her face. She was clothed in white and her garments shone with excessive lustre that was not dazzling, but soft. I did not see St. Joseph so distinctly, though I saw clearly that he was there, as in the visions of which I spoke before, [12] in which nothing is seen. Our Lady seemed to be very young.

17. When they had been with me for a while,−−I, too, in the greatest delight and joy, greater than I had ever had before, as I think, and with which I wished never to part,−−I saw them, so it seemed, ascend up to heaven, attended by a great multitude of angels. I was left in great loneliness, though so comforted and raised up, so recollected in prayer and softened, that I was for some time unable to move or speak−−being, as it were, beside myself. I was now possessed by a strong desire to be consumed for the love of God, and by other affections of the same kind. Everything took place in such a way that I could never have a doubt−−though I often tried−−that the vision came from God. [13] It left me in the greatest consolation and peace.

18. As to that which the Queen of the Angels spoke about obedience, it is this: it was painful to me not to subject the monastery to the Order, and our Lord had told me that it was inexpedient to do so. He told me the reasons why it was in no wise convenient that I should do it but I must send to Rome in a certain way, which He also explained; He would take care that I found help there: and so I did. I sent to Rome, as our Lord directed me,−−for we should never have succeeded otherwise,−−and most favourable was the result.

19. And as to subsequent events, it was very convenient to be under the Bishop, [14] but at that time I did not know him, nor did I know what kind of a superior he might be. It pleased our Lord that he should be as good and favourable to this house as it was necessary he should be on account of the great opposition it met with at the beginning, as I shall show hereafter, [15] and also for the sake of bringing it to the condition it is now in. Blessed be He who has done it all! Amen.

|

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved