THE THREE AGES OF THE INTERIOR LIFE: VOLUME 1

PRELUDE OF ETERNAL LIFE

By Reverend Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange O.P.

Translated by Sister M. Timothea Doyle

Copyright 1948, St. Louis, B. Herder Book Co., US.

Reverend Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange O.P. was professor of Dogma and Mystical Theology in the Angelico, Rome.

This is Volume 1 containing Parts; “The Sources of the Interior Life and its End” and “The Purification of the Soul in Beginners”.

Volume 2 containing Parts; “The Illuminative Way of Proficients”, “The Unitive Way of the Perfect” and “Extraordinary Graces” is also available.

This work is published for the greater Glory of Jesus Christ through His most Holy Mother Mary and for the sanctification of the militant Church and her members.

PUBLISHER

INDEX

THE THREE AGES OF THE INTERIOR LIFE: VOLUME 1

PART 1—THE SOURCES OF THE INTERIOR LIFE AND ITS END

PART 2—THE PURIFICATION OF THE SOUL IN BEGINNERS

THE THREE AGES OF THE INTERIOR LIFE: VOLUME 1

PREFACE

This work represents the summary of a course in ascetical and mystical theology which we have been giving for twenty years at the Angelicum in Rome. In this book we take up in a simpler and higher manner the study of the same subjects that we treated in two other works: Christian Perfection and Contemplation and L’ amour de Dieu et la croix de Jesus. Complying with a request, we offer in this volume our preceding research in the form of a synthesis, in which the different parts mutually balance and illuminate each other. In accordance with advice from various groups, we have eliminated from this exposition discussions to which it is no longer necessary to return. The book thus conceived is accessible to all interior souls.

We have not given this study the form of a manual because we are not seeking to accumulate knowledge, as is too often done in academic overloading, but to form the mind, to give it the firmness of principles and the suppleness required for the variety of their applications, in order that it may thus be capable of judging the problems which may arise. The humanities were formerly conceived in this fashion, whereas often today minds are transformed into manuals, into repertories, or even into collections of opinions and of formulas, whose reasons and profound consequences they do not seek to know.

Moreover, questions of spirituality, because they are most vital and at times most hidden, do not easily fall into the framework of a manual; or to put the matter more clearly, great risk is run of being superficial in materially classifying things and in substituting an artificial mechanism for the profound dynamism of the life of grace, of the infused virtues, and of the gifts. This explains why the great spiritual writers have not set forth their thought under this schematic form, which risks giving us a skeleton where we seek for life.

In these questions we have followed particularly three doctors of the Church who have treated these matters, each from his own point of view: St. Thomas, St. John of the Cross, and St. Francis de Sales. In the light of the theological principles of St. Thomas, we have tried to grasp what is most traditional in the mystical doctrine of The Dark Nightby St. John of the Cross and in the Treatise on the Love of God by St. Francis de Sales.

We have thus found a confirmation of what we believe to be the truth about the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith, which seems to us more and more to be in the normal way of sanctity and to be morally necessary to the full perfection of Christian life. In certain advanced souls, this infused contemplation does not yet appear as a habitual state, but from time to time as a transitory act, which in the interval remains more or less latent, although it throws its light on their entire life. However, if these souls are generous, docile to the Holy Ghost, faithful to prayer and to continual interior recollection, their faith becomes increasingly contemplative, penetrating, and full of savor, and it directs their action while making it ever more fruitful. In this sense, we maintain and we explain what seems to us the traditional teaching, which is more and more accepted today: namely, that the normal prelude of the vision of heaven, the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith, is, by docility to the Holy Ghost, prayer, and the cross, accessible to all fervent interior souls.

We believe also that, according to the doctrine of the greatest spiritual writers, notably of St. John of the Cross, there is a degree of perfection that is not obtained without the passive purifications, properly so called, which are a mystical state. This seems to us clearly indicated by all the teaching of St. John of the Cross on these passive purifications, and in particular by these two texts of capital importance from The Dark Night: “The night of sense is common, and the lot of many: these are the beginners”; “In the blessed night of the purgation of sense, the soul began to set out on the way of the spirit, the way of beginners and proficients, which is also called the illuminative way, or the way of infused contemplation, wherein God Himself teaches and refreshes the soul without meditation or any active efforts that itself may deliberately make.”1

We have never said, moreover, as some have asserted we did, that “the state of infused contemplation, properly so called, is the only normal way to reach the perfection of charity.” This infused contemplation, in fact, generally begins only with the passive purification of the senses, or, according to St. John of the Cross, at the beginning of the full illuminative way such as he describes it. Many souls are, therefore, in the normal way of sanctity before receiving infused contemplation, properly so called; but this contemplation, we say, is in the normal way of sanctity, at the summit of this way.

Without fully agreeing with us, a contemporary theologian, who is a professor of ascetical and mystical theology in the Gregorian University, wrote about our book, Christian Perfection and Contemplation, and that of Father Joret, O.P., La contemplation mystique d’apres saint Thomas d’Aquin: “No one could seriously dispute the fact that this doctrine is remarkably constructed and superbly arrived at; that it sets forth with beautiful lucidity the spiritual riches of Dominican theology in the definitive form given to it in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by the great interpreters of St. Thomas, namely, Cajetan, Banez, and John of St. Thomas; that the synthesis thus presented groups in a strong and harmonious unity a considerable mass of teaching and experience of Catholic spiritual tradition; and that it allows the full value of many of the most beautiful pages of our great contemplatives to be brought out.”2

The author of these lines adds that everything in this synthesis is not of equal value and does not have the same authority. It is certain that after the truths of faith and the commonly received theological conclusions, which represent what is surest in the sum of theological science, what we put forward on the authority of St. Thomas and of his best commentators does not command our adherence to the same extent as the principles which are its foundation. Yet it is difficult to subtract from this synthesis a single important element without compromising its solidity and harmony.

Has not a notable harmony already been realized when we consider that the most attentive critics recognize the admirable construction and superb growth of a doctrine?

The Carmelite Congress held at Madrid in 1923, the conclusions of which were published in the review, El Monte Carmela (Burgos), May, 1923, recognized the truth of these two important points on the subject of infused contemplation (Theme V): “The state of contemplation is characterized by the growing predominance of the gifts of the Holy Ghost and by the superhuman mode with which all good actions are performed. As the virtues find their ultimate perfection in the gifts, and as the gifts find their perfect actualization in contemplation, it follows that contemplation is the ordinary ‘way’ of sanctity and of habitually heroic virtue.”

In his Precis de theologie ascetique et mystique (1928), Father Tanquerey, the Sulpician, joins also in this teaching, to the extent that he writes:

“When infused contemplation is considered independently of the extraordinary mystical phenomena that sometimes accompany it, it is not something miraculous or abnormal, but the result of two causes: the growth of our supernatural organism, especially of the gifts of the Holy Ghost, and of an operating grace which is itself in no way miraculous. . . . This doctrine seems clearly to be the traditional doctrine such as it is found in the works of mystical authors, from Clement of Alexandria to St. Francis de Sales. . . . Almost all these authors treat contemplation as the normal crowning of Christian life.3

“With the same meaning we can quote what St. Ignatius of Loyola says in a well-known letter to St. Francis Borgia. (Rome, 1548): “Without these gifts (divine impressions and illuminations), all our thoughts, words, and works are imperfect, cold, and troubled. We ought to desire these gifts that by them our works may become just, ardent, and clear for the greater service of God.” In 1924, Father Peeters, S.J., in chapter 8 of his interesting study, Vers l’union divine par les exercices de saint Ignace (Museum Lessianum, Bruges), wrote: “What does the author of the Exercises think of the universal vocation to the mystical state? It is impossible to admit that he considers it a quasi-abnormal exception. . . . His optimistic confidence in the divine liberality is known. “Few men,” said the saint, “suspect what God would make them if they placed no obstacle to His work” Such, in truth, is human weakness that only a singularly generous elite accepts the formidable exigencies of grace. Heroism never was and never will be banal, and sanctity cannot be conceived without heroism. . . .

“In the entire book of the Exercises, with an insistence revealing his deep conviction, he offers to his generous disciples the unlimited hope of the divine communications, the possibility of attaining God, of tasting the sweetness of the divinity, of entering into immediate communication with God, of aspiring to the divine familiarity. He said: “The more the soul attaches itself to God and shows itself generous toward Him, the more apt it becomes to receive graces and spiritual gifts in abundance.” . . .

“This is putting it still too mildly. The graces of prayer seem to him not only desirable, but hypothetically necessary to eminent sanctity, especially in apostolic men.4

This is what we wished to show in the present work. Agreement on these great questions is increasingly acknowledged, and is also more real than it seems. Some, who are professional theologians as we ourselves are, consider the life of grace, the seed of glory, in itself in order to judge what ought to be the full, normal development of the infused virtues and of the gifts, the proximate disposition for receiving the beatific vision without passing through purgatory; in other words, their full development in a completely purified soul that has profited richly by the trials of life on earth and no longer has to expiate its faults after death. Whence we conclude that infused contemplation is, in principle or in theory, in the normal way of sanctity, although there are exceptions arising from the individual temperament or from absorbing occupations or from less favorable surroundings, and so on.5

Other authors, considering especially the facts, or the individual souls in which the life of grace exists, declare there are truly generous interior souls that do not reach this summit, which is, nevertheless, in itself the full, normal development of habitual grace, of the infused virtues, and of the gifts.

Spiritual theology, like every science, ought to consider the interior life as such, and not in a given individual in the midst of rather unfavorable given circumstances. Because there are stunted oaks, it does not follow that the oak is not a tall tree. Spiritual theology, while noting the exceptions that may arise from the absence of a given condition, ought especially to establish the higher laws of the full development of the life of grace as such, and the proximate disposition to receive the beatific vision immediately in a fully purified soul.

Purgatory, being a punishment, presupposes a fault that we could have avoided and that we could have expiated before death by accepting the trials of the present life with an ever better will. We are seeking here to determine the normal way of sanctity or of a perfection such that one could enter heaven immediately after death. From this point of view, we must consider the life of grace inasmuch as it is the seed of eternal life, and consequently it is the correct idea of eternal life, the end of our course, which must illuminate the entire road to be traveled. Movement is not specified by its point of departure or by the obstacles it encounters, but by the end toward which it tends. Thus the life of grace must be defined by eternal life of which it is the seed; and then the proximate and perfect disposition to receive the beatific vision immediately is in the normal way of sanctity.

In the following pages we insist far more on the principles generally accepted in theology, by showing their value and their radiation, than on the variety of opinions on one particular point or another proposed by often quite secondary authors. There are some recent works, already indicated, which mention all these opinions in detail. We propose another aim, and that is why we quote mostly from the greatest masters. Constant recourse to the foundations of their doctrine seems to us what is most necessary for the formation of the mind, which is more important than erudition. The secondary ought not make us forget the primary, and the complexity of certain questions ought not to make us lose sight of the certitude of the great directive principles that illuminate all spirituality. We ought particularly not to be content with repeating these principles like I so many platitudes, but to scrutinize them, to probe their depths, and to revert to them continually that we may better understand I them.

Doubtless such a course of action lays one open to repetition; but those who seek true theological science over and above contingent opinions which may be in vogue for several years, know that it is above all wisdom. They know that it is not so much preoccupied with deducing new conclusions, but with connecting all the more or less numerous conclusions with the same higher principles, like the different sides of a pyramid with the same apex. Then the fact that in relation to every problem we recall the loftiest principle of the synthesis is not a repetition but a way of drawing near to circular contemplation, which, St. Thomas says,6 ever reverts to the same eminent truth the better to grasp all its potentialities, and which, like the flight of a bird, describes several times the same circle around the same point. This center, like the apex of a pyramid, is in its way a symbol of the single instant of immobile eternity, which corresponds to all the successive instants of time that passes. From this point of view, our readers will pardon us for repeating several times the same dominant themes which constitute the charm, the unity, and the grandeur of spiritual theology.

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

This translation of Father Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange’s synthesis of the spiritual life, Les Trois Ages de la Vie Interieure, has been made possible by the interest and encouragement of Mother Mary Samuel, O.P., Mother General of the Sinsinawa Dominican Sisters.

Gratitude is due especially to the Very Reverend Peter O’Brien, O.P., S.T.Lr., Ph.D., Provincial of the Province of St. Albert the Great, River Forest, Illinois, for reading the manuscript, to other Fathers of the Dominican House of Studies in River Forest for criticisms and helpful suggestions, and to Sister Mary Aquinas Devlin, O.P., Chairman of the Department of English, Rosary College, for reading the entire manuscript.

Grateful acknowledgement is also made to the Benedictines of Stanbrook Abbey for permission to use quotations from their editions ofThe Way of Perfection and The Interior Castle; to Thomas Baker for quotations from the Works of St. John of the Cross; to Benziger Brothers for the many quotations from their English edition of theSumma Theologica; to Burns, Oates, Washbourne for quotations fromThe Dialogue.

This translation is offered to Mary, Queen of the Most Holy rosary and Mediatrix of All Graces, and to St. Mary Magdalen, protectress of the Order of Preachers and patroness of the interior life, as a prayer that it may lead many souls to the contemplation of the mysteries of salvation in which they shared so profoundly.

Sister M. Timothea Doyle, O.P.

FOREWORD

Sister Mary Timothea Doyle has done us a real service in giving us this translation of Father R. Garrigou-Lagrange’s classical work Les Trois Ages de la Vie Interieure. Doctrinally sound, this work has been accepted for its clear presentation of the way of perfection or, as St. Francis de Sales calls it, the life of devotion. The author is profound in his studies without losing that clarity of thought which is so necessary and helpful in works on the spiritual life. Analyzing the teaching of the great masters through the centuries, he has succeeded in giving us a synthesis of their thought which cannot but be helpful to those who are seeking closer and closer union with God.

The basic thought of this book is given in the words of our Blessed Savior: “Be ye perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect.” We are called in our vocation as sons of God to dare to imitate divine perfection-to be participators of the divine nature. Our supernatural birthright, lost to us in Eden, was restored in the blood of the Savior on Calvary. Indeed human nature is weak, but in the grace of God it can soar to the heights of perfection and hold before it as its ideal the very perfection of God. To be in very truth in the light of Christian doctrine a son of God is the worthiest ambition of our souls.

The way is love. To be encompassed in the love of God for us and to seek always supernaturally to return to God love is the spiritual life of the Christian soul. Now love impels the soul to union with God, and God in His love gives the soul the capacity for supernatural union with Him. All the teachings on the spiritual life are synthesized in this one thought—love. Just how God leads the soul in divine love and how the soul may exercise itself in the discipline of love is the subject matter of the great works on the spiritual life.

Sublime indeed is the thought that Christian charity brings to our minds. We reach up to God, and God reaches down to us, and in divine love we are made sharers of the Divinity. All things we love in God, and because we love them in God we seek to realize in our use of them and relations with them the harmony of the divine will. Of its very nature charity is not quiescent but operative. The soul in the pursuit of the way of perfection labors tirelessly according to its state in life to bring all men to God. Were it to content itself with its own perfection, it would lose the very thing it seeks. How can we love God and not love with God? How can we find God without searching in love for the things which God loves? Certainly one of the fruits of the spiritual life is peace, but this peace postulates our conforming our wills with the divine will. All the noble aspirations of the heart of man, aspirations which so often seem unrealizable in our condition of human weakness, are answered in our seeking to be ever more and more perfect in the spiritual life.

Men are talking much these days about realism, and they tell us that in life idealism must yield to compromise. Yet in every circumstance in life we can be sons of God in supernatural union with Him. This fact is the very basis of true Christian realism. We must not and dare not be defeatists. What human nature can never do can be done in the supernatural power of divine grace. It is therefore opportune in these times to give us this translation of this classical work of the spiritual life because it strengthens us in our effort to work out more perfectly our vocation of sons of God. We can build a better world. Human weakness is not an impassable barrier. The Savior died on the cross for us and rose to glorious life. With the graces of Redemption we are strong enough to labor for the realization of God’s plan and on our way to heaven to love with an operative love all those whom we meet on our pilgrimage of life.

We hope that pious souls will read this book, ponder over its pages, and gain new strength from it. It is a challenge to Christians to arise and labor unceasingly for the kingdom of Christ—wherein there is peace and true progress.

Samuel Cardinal Stritch Archbishop of Chicago

INTRODUCTION

We propose in this book to synthesize two other works, Christian Perfection and Contemplation, and L’amour de Dieu et la croix de Jesus. In those two works we studied, in the light of the principles of St. Thomas, the main problems of the spiritual life and in particular one which has been stated more explicitly in recent years, namely: Is the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith and the union with God which results therefrom an intrinsically extraordinary grace, or is it, on the contrary, in the normal way of sanctity?

We purpose here to consider these questions again in a simpler and loftier manner, with the perspective needed the better to see the subordination of all the elements of the interior life in relation to union with God. With this end in view, we shall consider first of all the foundations of the interior life, then the elimination of obstacles, the progress of the soul purified and illuminated by the light of the Holy Ghost, the docility which it ought to have toward Him, and finally the union with God which the soul attains by this docility, by the spirit of prayer, and by the cross borne with patience, gratitude, and love.

By way of introduction, we shall briefly recall what constitutes the one thing necessary for every Christian, and we shall also recall how urgently this question is being raised at the present time.

As everyone can easily understand, the interior life is an elevated form of intimate conversation which everyone has with himself as soon as he is alone, even in the tumult of a great city. From the moment he ceases to converse with his fellow men, man converses interiorly with himself about what preoccupies him most. This conversation varies greatly according to the different ages of life; that of an old man is not that of a youth. It also varies greatly according as a man is good or bad.

As soon as a man seriously seeks truth and goodness, this intimate conversation with himself tends to become conversation with God. Little by little, instead of seeking himself in everything, instead of tending more or less consciously to make himself a center, man tends to seek God in everything, and to substitute for egoism love of God and of souls in Him. This constitutes the interior life. No sincere man will have any difficulty in recognizing it. The one thing necessary which Jesus spoke of to Martha and Mary7 consists in hearing the word of God and living by it.

The interior life thus conceived is something far more profound and more necessary in us than intellectual life or the cultivation of the sciences, than artistic or literary life, than social or political life. Unfortunately, some great scholars, mathematicians, physicists, and astronomers have no interior life, so to speak, but devote themselves to the study of their science as if God did not exist. In their moments of solitude they have no intimate conversation with Him. Their life appears to be in certain respects the search for the true and the good in a more or less definite and restricted domain, but it is so tainted with self-love and intellectual pride that we may legitimately question whether it will bear fruit for eternity. Many artists, literary men, and statesmen never rise above this level of purely human activity which is, in short, quite exterior. Do the depths of their souls live by God? It would seem not.

This shows that the interior life, or the life of the soul with God, well deserves to be called the one thing necessary, since by it we tend to our last end and assure our salvation. This last must not be too widely separated from progressive sanctification, for it is the very way of salvation.

There are those who seem to think that it is sufficient to be saved and that it is not necessary to be a saint. It is clearly not necessary to be a saint who performs miracles and whose sanctity is officially recognized by the Church. To be saved, we must take the way of salvation, which is identical with that of sanctity. There will be only saints in heaven, whether they enter there immediately after death or after purification in purgatory. No one enters heaven unless he has that sanctity which consists in perfect purity of soul. Every sin though it should be venial, must be effaced, and the punishment due to sin must be borne or remitted, in order that a soul may enjoy forever the vision of God, see Him as He sees Himself, and love Him as He loves Himself. Should a soul enter heaven before the total remission of its sins, it could not remain there and it would cast itself into purgatory to be purified.

The interior life of a just man who tends toward God and who already lives by Him is indeed the one thing necessary. To be a saint, neither intellectual culture nor great exterior activity is a requisite; it suffices that we live profoundly by God. This truth is evident in the saints of the early Church; several of those saints were poor people, even slaves. It is evident also in St. Francis, St. Benedict Joseph Labre, in the Cure of Ars, and many others. They all had a deep understanding of these words of our Savior: “For what doth it profit a man, if he gain the whole world, and suffer the loss of his own soul?”8 If people sacrifice so many things to save the life of the body, which must ultimately die, what should we not sacrifice to save the life of our soul, which is to last forever? Ought not man to love his soul more than his body? “Or what exchange shall a man give for his soul?” our Lord adds.9 “One thing is necessary,” He tells us.10 To save our soul, one thing alone is necessary: to hear the word of God and to live by it. Therein lies the best part, which will not be taken away from a faithful soul even though it should lose everything else.

II. THE QUESTION OF THE ONE THING NECESSARY AT THE PRESENT TIME

What we have just said is true at all times; but the question of the interior life is being more sharply raised today than in several periods less troubled than ours. The explanation of this interest lies in the fact that many men have separated themselves from God and tried to organize intellectual and social life without Him. The great problems that have always preoccupied humanity have taken on a new and sometimes tragic aspect. To wish to get along without God, first Cause and last End, leads to an abyss; not only to nothingness, but also to physical and moral wretchedness that is worse than nothingness. Likewise, great problems grow exasperatingly serious, and man must finally perceive that all these problems ultimately lead to the fundamental religious problem; in other words, he will finally have to declare himself entirely for God or against Him. This is in its essence the problem of the interior life. Christ Himself says: “He that is not with Me is against Me.”11

The great modern scientific and social tendencies, in the midst of the conflicts that arise among them and in spite of the opposition of those who represent them, converge in this way, whether one wills it or not, toward the fundamental question of the intimate relations of man with God. This point is reached’ after many deviations. When man will no longer fulfill his great religious duties toward God who created him and who is his last End, he makes a religion for himself since he absolutely cannot get along without religion. To replace the superior ideal which he has abandoned, man may, for example, place his religion in science or in the cult of social justice or in some human ideal, which finally he considers in a religious manner and even in a mystical manner. Thus he turns away from supreme reality, and there arises a vast number of problems that will be solved only if he returns to the fundamental problem of the intimate relations of the soul with God.

It has often been remarked that today science pretends to be a religion. Likewise socialism and communism claim to be a code of ethics and present themselves under the guise of a feverish cult of justice, thereby trying to captivate hearts and minds. As a matter of fact, the modern scholar seems to have a scrupulous devotion to the scientific method. He cultivates it to such a degree that he often seems to prefer the method of research to the truth. If he bestowed equally serious care on his interior life, he would quickly reach sanctity. Often, however, this religion of science is directed toward the apotheosis of man rather than toward the love of God. As much must be said of social activity, particularly under the form it assumes in socialism and communism. It is inspired by a mysticism which purposes a transfiguration of man, while at times it denies in the most absolute manner the rights of God.

This is simply a reiteration of the statement that the religious problem of the relations of man with God is at the basis of every great problem. We must declare ourselves for or against Him; indifference is no longer possible, as our times show in a striking manner. The present world-wide economic crisis demonstrates what men can do when they seek to get along without God.

Without God, the seriousness of life gets out of focus. If religion is no longer a grave matter but something to smile at, then the serious element in life must be sought elsewhere. Some place it, or pretend to place it, in science or in social activity; they devote the selves religiously to the search for scientific truth or to the establishment of justice between classes or peoples. After a while they are forced to perceive that they have ended in fearful disorder and that the relations between individuals and nations become more and more difficult, if not impossible. As St. Augustine and St. Thomas12 have said, it is evident that the same material goods, as opposed to those of the spirit, cannot at one and the same time belong integrally to several persons. The same house, the same land, cannot simultaneously belong wholly to several men, nor the same territory to several nations. As a result, interests conflict when man feverishly makes these lesser goods his last end.

St. Augustine, on the other hand, insists on the fact that the same spiritual goods can belong simultaneously and integrally to all and to each individual in particular. Without doing harm to another, we can fully possess the same truth, the same virtue, the same God. This is why our Lord says to us: “Seek ye therefore first the kingdom of God and His justice; and all these things shall be added unto you.”13 Failure to hearken to this lesson, is to work at one’s destruction and to verify once more the words of the Psalmist: “Unless the Lord build the house, they labor in vain that build it. Unless the Lord keep the city, he watcheth in vain that keepeth it.”14

If the serious element in life is out of focus, if it no longer is concerned with our duties toward God, but with the scientific and social activities of man; if man continually seeks himself instead of God, his last End, then events are not slow in showing him that he has taken an impossible way, which leads not only to nothingness, but to unbearable disorder and misery. We must again and again revert to Christ’s words: “He that is not with Me, is against Me: and he that gathereth not with Me, scattereth.”15 The facts confirm this declaration.

We conclude logically that religion can give an efficacious and truly realistic answer to the great modern problems only if it is a religion that is profoundly lived, not simply a superficial and cheap religion made up of some vocal prayers and some ceremonies in which religious art has more place than true piety. As a matter of fact, no religion that is profoundly lived is without an interior life, without that intimate and frequent conversation which we have not only with ourselves but with God.

The last encyclicals of Pope Pius XI make this clear. To respond to what is good in the general aspirations of nations, aspirations to justice and charity among individuals, classes, and peoples, the Holy Father wrote the encyclicals on Christ the King, on His sanctifying influence in all His mystical body, on the family, on the sanctity of Christian marriage, on social questions, on the necessity of reparation, and on the missions. In all these encyclicals he deals with the reign of Christ over all humanity. The logical conclusion to be drawn is that religion, the interior life, must be profound, must be a true life of union with God if it is to keep the pre-eminence it should have over scientific and social activities. This is a manifest necessity.

How shall we deal with the interior life? We shall not take up in a technical manner many questions about sanctifying grace and the infused virtues that have been treated at length by theologians. We assume them here, and we shall revert to them only in the measure necessary for the understanding of what the spiritual life should be.

Our aim is to invite souls to become more interior and to tend to union with God. To do so, two very different dangers must be avoided.

Rather frequently the spirit animating scientific research even in these matters tarries over details to such an extent that the mind is turned away from the contemplation of divine things. The majority of interior souls do not need many of the critical studies indispensable to the theologian. To understand them, they would need a philosophical initiation which they do not possess and which, in a sense, would hamper them who in an instant and in a different manner go higher, as in the case of St. Francis of Assisi. He was astonished to see that in the course of philosophy given to his religious, time was taken to prove the existence of God. Today, occasionally exaggerated specialization in studies produces in many minds a lack of the general view needed to judge wisely of things, even of those in which they are especially interested and whose relation with every thing else they no longer see. The cult of detail ought not to make us lose sight of the whole. Instead of becoming spiritual, we would then become materialistic, and under pretext of exact and detailed learning, we would turn away from the true interior life and from lofty Christian wisdom.

On the other hand, many books on religious subjects that are written in a popular style, and many pious books lack a solid doctrinal foundation. Popularization, because the kind of simplification imposed upon it is material rather than formal, often avoids the examination of certain fundamental and difficult problems from which, nevertheless, light would come, and at times the light of life.

To avoid these two opposite dangers, we shall follow the way pointed out by St. Thomas, who was not a popularizer and who is still the great classic authority on theology. He rose from the learned complexity of his first works and of the Quaestiones disputatae to the superior simplicity of the most beautiful articles of the Summa theologica. He ascended to this height so well that at the end of his life, absorbed in lofty contemplation, he could not dictate the end of his Summa because he could no longer descend to the complexity of the questions and articles that he still wished to compose.

The cult of detail and that of superficial simplification, each in its way alienates the soul from Christian contemplation, which rises above these opposing deviations like a summit toward which all prayerful souls tend.

IV. THE OBJECT OF ASCETICAL AND MYSTICAL THEOLOGY

One sees from the matter which ascetical and mystical theology should treat that it is a branch or a part of theology, an application of theology to the direction of souls. It must, therefore, proceed under the light of revelation, which alone gives a knowledge of the nature of the life of grace and of the supernatural union of the soul with God.

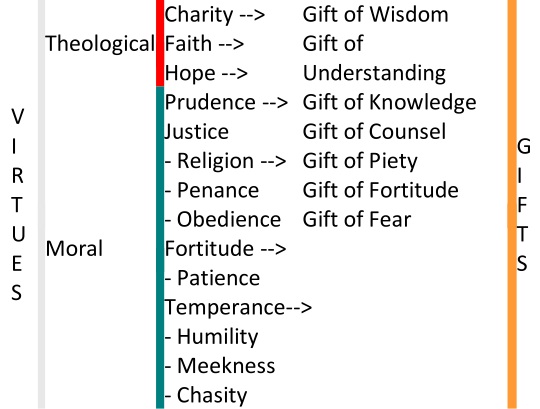

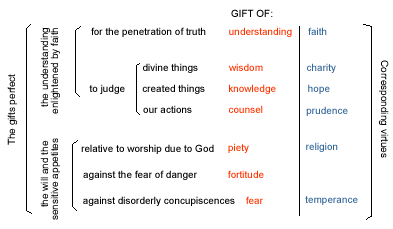

This part of theology is, above all, a development of the treatise on the love of God and of that on the gifts of the Holy Ghost, to show how they are applied or to lead souls to divine union.16 Similarly, casuistry is, in a less elevated domain, an application of moral theology to the practical discernment of what is obligatory under pain of mortal or venial sin. Moral theology ought to treat, not only of sins to be avoided, but of virtues to be practiced, and of docility in following the inspirations of the Holy Ghost. From this point of view, its applications are called ascetical and mystical theology.

Ascetical theology treats especially of the mortification of vices or defects and of the practice of the virtues. Mystical theology treats principally of docility to the Holy Ghost, of the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith, of the union with God which proceeds from it, and also of extraordinary graces, such as visions and revelations, which sometimes accompany infused contemplation.17

We shall examine the question whether ascetical theology is essentially ordained to mystical theology by asking whether the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith and the union with God that results from it is an essentially extraordinary grace, such as visions an revelations, or whether in the perfect it is not rather the eminent but normal exercise of the gifts of the Holy Ghost, which are in all the just. The answer to this question, which has been discussed several times in recent years, will form the conclusion of this work.

V. THE METHOD OF ASCETICAL AND MYSTICAL THEOLOGY

We shall limit ourselves here to what is essential in regard to the method to be followed.18 We must avoid two contrary deviations that are easily grasped: one would result from the almost exclusive use of the descriptive or inductive method, the other from a contrary excess.

The almost exclusive use of the descriptive or inductive method would lead us to forget that ascetical and mystical theology is a branch of theology, and we would end by considering it a part of experimental psychology. We would thus assemble only the material of mystical theology. By losing the directing light, all would be impoverished and diminished. Mystical theology must be set forth by the great principles of theology on the life of grace, on the infused virtues, and on the seven gifts; in so doing, light is shed on all of it, and one is face to face with a science and not a collection of more or less well described phenomena.

If the descriptive method were used almost exclusively, we would be struck especially by the more or less sensible signs of the mystical state and not by the basic law of the progress of grace, whose essential supernaturalness is of too elevated an order to fall under the grasp of observation. More attention might then be given to certain extraordinary and, so to speak, exterior graces, such as visions, revelations, stigmata, than to the normal and elevated development of sanctifying grace, of the infused virtues, and of the gifts of the Holy Ghost. By so doing, we might be led to confound with what is essentially extraordinary that which is only extrinsically so, that is, what is eminent but normal; to confound intimate union with God in its elevated forms with the extraordinary and relatively inferior graces which sometimes accompany it.

Lastly, the exclusive use of the descriptive method might give too much importance to this easily established fact, that intimate union with God and the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith are relatively rare. This idea might lead us to think that all interior and generous souls are not called to it, even in a general and remote manner.19 This would be to forget the words of our Lord so frequently quoted by the mystics in this connection: “Many are called, but few are chosen.”

On the other hand, care must be taken to avoid another deviation that would spring from the almost exclusive use of the deductive theological method. Some souls that are rather inclined to over-simplify things would be led to deduce the solution of the most difficult problems of spirituality by starting from the accepted doctrine in theology about the infused virtues and the gifts, as it is set forth by St. Thomas, without sufficiently considering the admirable descriptions given by St. Teresa, St. John of the Cross, St. Francis de Sales, and other saints, of the various degrees of the spiritual life, especially of the mystical union. It is to these facts that the principles must be applied, or rather it is these facts, first of all well understood in themselves, that must be illuminated by the light of principles, especially to discern what is truly extraordinary in them and what is eminent but normal.

The excessive use of the deductive method in this case would lead to a confusion radically opposed to the one indicated above. Since, according to tradition and St. Thomas, the seven gifts of the Holy Ghost are in every soul in the state of grace, we might thus be inclined to believe that the mystical state or infused contemplation is very frequent, and we might confound with them what is only their prelude, as simplified effective prayer.20 We would thus be led not to take sufficiently into account the concomitant phenomena of certain degrees of the mystical union, such as suspension of the faculties and ecstasy, and we would fall into the opposite extreme from that of the partisans of the solely descriptive method.

Practically, as a result of these two excesses two extremes also are to be avoided in spiritual direction: advising souls to leave the ascetical way too soon or too late. We will discuss this matter at length in the course of this work.

Obviously the two methods, the inductive and the deductive, or the analytic and the synthetic, must be combined.

The concepts and the facts of the spiritual life must be analyzed. First of all, must be analyzed the concepts of the interior life and of Christian perfection, of sanctity, which the Gospel gives us, in order that we may see clearly the end proposed by the Savior Himself to all interior souls, and see this end in all its elevation without in any way diminishing it. Then must be analyzed the facts: the imperfections of beginners, the active and passive purifications, the various degrees of union, and so on, to distinguish what is essential in them and what is accessory.

After this work of analysis, we must make a synthesis and point out what is necessary or very useful and desirable to reach the full perfection of Christian life, and what, on the other hand, is properly extraordinary and in no way required for the highest sanctity.21

Several of these questions are very difficult, either because of the elevation of the subject treated, or because of the contingencies that are met with in the application and that depend on the temperament of the persons to be directed or on the good pleasure of God, who, for example, sometimes grants the grace of contemplation to beginners and withdraws it temporarily from advanced souls. Because of these multiple difficulties, the study of ascetical and mystical theology requires a profound knowledge of theology, especially of the treatises on grace, on the infused virtues, on the gifts of the Holy Ghost in their relations with the great mysteries of the Trinity, the Incarnation, the redemption, and the Blessed Eucharist. It requires also familiarity with the great spiritual writers, especially those who have been designated by the Church as guides in these matters.

VI. THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN ASCETICAL AND MYSTICAL THEOLOGY AND THEIR RELATIONS TO EACH OTHER

We must recall here the division between ascetical and mystical theology that was generally accepted until the eighteenth century, and then the modification that Scaramelli and those who followed him introduced at that time. The reader will, therefore, more readily understand why, with several contemporary theologians, we return to the division that seems to us truly traditional and conformable to the principles of the great masters.

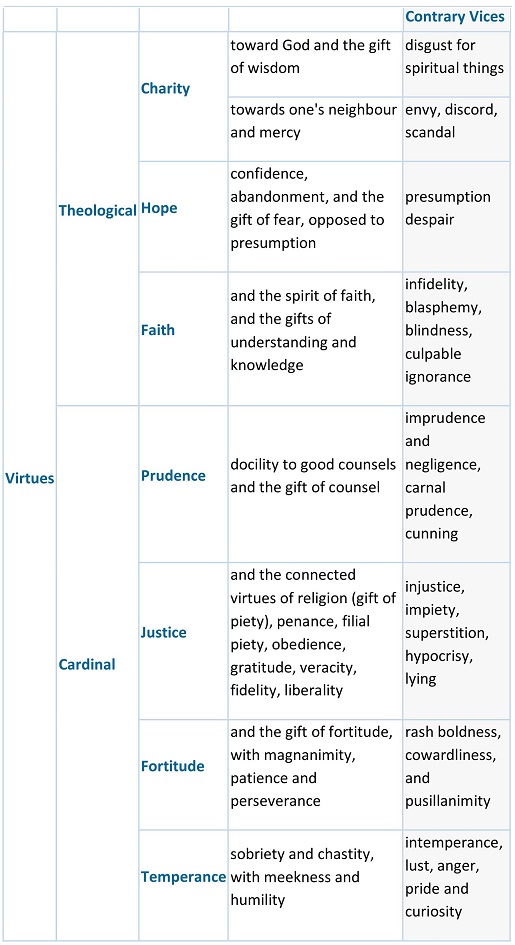

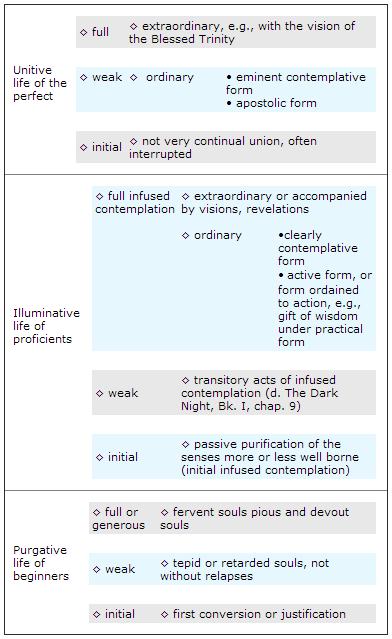

Until the eighteenth century, authors generally set forth under the titleTheologia mystica all the questions that ascetical and mystical theology treats of today. This is evident from the title of the works written by Blessed Bartholomew of the Martyrs, O.P., Philip of the Blessed Trinity, O.C.D., Anthony of the Holy Ghost, O.C.D., Thomas Vallgornera, O.P., Schram, O.S.B. ., and others. Under the title Theologia mystica all these authors treated of the purgative way of beginners, of the illuminative way of proficients, and of the unitive way of the perfect. In one or the other of these last two parts, they spoke of infused contemplation and the extraordinary graces which sometimes accompany it, that is to say, visions, revelations, and like favors. Moreover, in their introduction these authors customarily treated of experimental mystical theology, that is, of infused contemplation itself, for their treatises were directed to it and to the intimate union with God which results from it.

An example of this division which was generally admitted in former times may be found in Vallgornera’s Mystica theologia divi Thomae(1662). He closely follows the Carmelite, Philip of the Blessed Trinity, by linking the division Philip gave with that of earlier authors and with certain characteristic texts from the works of St. John of the Cross on the period when the passive purifications of the senses and of the spirit generally appear. He divides his treatise for contemplatives into three parts (the purgative way, the illuminative way, the unitive way).

I. The purgative way, proper to beginners, in which he treats of the active purification of the external and internal senses, of the passions, of the intellect and the will, by mortification, meditation, and prayer, and finally of the passive purification of the senses, which is like a second conversion and in which infused contemplation begins. It is the transition to the illuminative way.

This last point is of prime importance in this division, and it conforms closely to two of the most important texts from the works of St. John of the Cross: “The night of sense is common, and the lot of many: these are the beginners.”22 “The soul began to set out on the way of the spirit, the way of proficients, which is also called the illuminative way, or the way of infused contemplation, wherein God Himself teaches and refreshes the soul.”23 Infused contemplation begins, according to St. John of the Cross, with the passive purification of the senses, which thus marks the transition from the way of beginners to that of proficients. Vallgornera clearly preserves this doctrine in this division as well as in the one that follows.

2. The illuminative way, proper to proficients, in which, after a preliminary chapter on the divisions of contemplation, are discussed the gifts of the Holy Ghost, infused contemplation, which proceeds especially from the gifts of understanding and wisdom and which is declared desirable for all interior souls,24 as morally necessary for the full perfection of Christian life. After several articles relating to extraordinary graces (visions, revelations, interior words), this second part of the work closes with a chapter of nine articles dealing with the passive purification of the spirit, which marks the passage to the unitive way. This also is what St. John of the Cross taught.25

3. The unitive way, proper to the perfect, in which is discussed the intimate union of the contemplative soul with God and its degrees up to the transforming union. Vallgornera considers this division traditional, truly conformable to the doctrine of the fathers, to the principles of St. Thomas, and to the teaching of the greatest mystics who have written on the three ages of the spiritual life, noting how the transition from one to the other is generally made.26

In the eighteenth century, Scaramelli (1687–1752), who was followed by many authors of that period, proposed an entirely different division. First of all, he does not treat of ascetical and mystical theology in the same work but in two separate works, comprising four treatises:(1) Christian perfection and the means that lead to it; (2) Obstacles (or the purgative way);(3) The proximate dispositions to Christian perfection, consisting in the moral virtues in the perfect degree (or the way of proficients); (4) The essential perfection of the Christian, consisting in the theological virtues and especially in charity (the love of conformity in the perfect). This ascetical directory does not, so to speak, discuss the gifts of the Holy Ghost. The high degree of the moral and theological virtues therein described is, nevertheless, not reached without the gifts, according to the common teaching of the doctors.

The Direttorio mistico is composed of five treatises: (1) The introduction, in which are discussed the gifts of the Holy Ghost and graces gratis datae; (2) Acquired and infused contemplation, for which the gifts suffice, as Scaramelli recognizes (chap. 14); (3) The degrees of indistinct infused contemplation, from passive recollection to the transforming union. In chapter 32, Scaramelli admits that several authors teach that infused contemplation may be humbly desired by all interior souls, but he ends by concluding that practically it is better not to desire it before receiving a special call: “altiora te ne quaesieris”;27 (4) The degrees of distinct infused contemplation (visions and extraordinary interior words); (5) The passive purifications of the senses and the spirit.

It is surprising to find only at the end of this mystical directory the treatise on the passive purification of the senses which, in the opinion of St. John of the Cross and the authors quoted above, marks the entrance into the illuminative way.

By a fear of quietism, at times excessive, which cast discredit on mystical theology, many authors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries followed Scaramelli, who was most highly esteemed by them. According to their point of view, ascetical theology treats of the exercises which lead to perfection according to the ordinary way, whereas mystical theology treats of the extraordinary way, to which the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith would belong. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the present period this tendency appears again clearly marked in the study of mental prayer by Father de Maumigny, S.].,28 in the writings of Bishop Farges,29 and in the work of the Sulpician, Father Pourrat.30 According to these authors, ascetical theology is not only distinct from mystical theology, but is separated from it; it is not ordained to it, for mystical theology treats only of extraordinary graces which are not necessary for the full perfection of Christian life. Taking this point of view, some writers even maintained that, since St. Teresa of the Child Jesus did not receive extraordinary graces, she sanctified herself by the ascetical way and not by the mystical way. Strange supposition.

In the last thirty years, Father Arintero, O.P.,31 Monsignor Saudreau,32 the Eudist, Father Lamballe,33 Father de la Taille, S.J.,34 Father Gardeil, O.P.,35 Father Joret, O.P.,36 Father Gerest,37 several Carmelites in France and in Belgium,38 Benedictines such as Dom Huijben, Dom Louismet, and several others,39 examined attentively the bases of the position taken by Scaramelli and his successors.

As we have shown at length elsewhere,40 we have been led, as these authors were, to formulate the three following questions on the subject of the division given by Scaramelli and his successors:

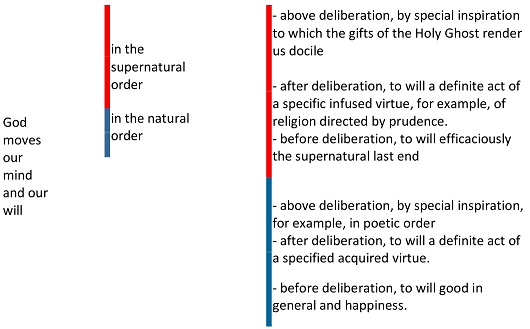

I. Is this absolute distinction or separation between ascetical and mystical theology entirely traditional, or is it not rather an innovation made in the eighteenth century? Does it conform to the principles of St. Thomas and to the doctrine of St. John of the Cross? St. Thomas teaches that the seven gifts of the Holy Ghost, while specifically distinct from the infused virtues, are, nevertheless, in all the just, for they are connected with charity.41 He says, moreover, that they are necessary for salvation, for a just man may find himself in difficult circumstances where even the infused virtues would not suffice and where he needs a special inspiration of the Holy Ghost to which the gifts render us docile. St. Thomas likewise considers that the gifts intervene rather frequently in ordinary circumstances to give to the acts of the virtues in generous interior souls a perfection, an impulse, and a promptness which would not exist without the superior intervention of the Holy Ghost.42

On the other hand, St. John of the Cross, as we have said, wrote these most significant words: “The passive purification of the senses is common. It takes place in the greater number of beginners.”43 According to St. John, infused contemplation begins with it. And again he says: “The soul began to set out on the way of the spirit, the way of proficients, which is also called the illuminative way, or the way of infused contemplation, wherein God Himself teaches and refreshes the soul.”44 In this text the holy doctor did not wish to affirm something accidental, but something normal. St. Francis de Sales expresses the same thought45. The division proposed by Scaramelli could not be reconciled with this doctrine because he speaks of the passive purifications of the senses and the spirit only at the end of the unitive way, as not only eminent but essentially extraordinary.

2. It may be asked whether such a distinction or separation between ascetical and mystical theology does not diminish the unity of the spiritual life. A good division, in order to be necessarily basic and not superficial an accidental, should rest on the very definition of the whole to be divided, on the nature of, this whole, which in this case is the life of grace, called by tradition the “grace of the virtues and the gifts”;46 for the seven gifts of the Holy Ghost, being connected with charity, are part of the spiritual organism and are necessary for perfection.

3. Does not the sharply marked division between ascetical and mystical theology, proposed by Scaramelli and several others, also diminish the elevation of evangelical perfection, when it treats of it in ascetical theology, taking away from it the gifts of the Holy Ghost, the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith, and the union which results therefrom? Does not this new conception weaken the motives for practicing mortification and for exercising the virtues, and does it not do so by losing sight of the divine intimacy for which this work should prepare us? Does it not lessen the illuminative and unitive ways when it speaks of them simply from the ascetical point of view? Can these two ways normally exist without the exercise of the gifts of the Holy Ghost proportioned to that of charity and of the other infused virtues? Finally, does not this new conception diminish also the importance and the gravity of mystical theology, which, separated thus from ascetical theology, seems to become a luxury in the spirituality of some privileged souls, and one that is not without danger?

Are there six ways (three ascetical and ordinary, and three mystical and extraordinary, not only in fact but in essence) and not just three ways, three ages of the spiritual life, as the ancients used to say?

As soon as ascetical treatises on the illuminative and unitive ways are separated from mystical theology, they contain scarcely more than abstract considerations first on the moral and then on the theological virtues. On the other hand, if they treat practically and concretely of the progress and the perfection of these virtues, as Scaramelli does in his Direttorio ascetico, this perfection, according to the teaching of St. John of the Cross, is manifestly unattainable without the passive purifications, at least without that of the senses, and without the cooperation of the gifts of the Holy Ghost. The question then arises whether the passive purification of the senses in which, according to St. John of the Cross, infused contemplation and the mystical life, properly so called, begins is something essentially extraordinary or, on the contrary, a normal grace, the principle of a second conversion, which marks the entrance into the illuminative way. Without this passive purification, can a soul reach the perfection which Scaramelli speaks of in his Direttorio ascetico? Let us not forget what St. Teresa says: “For instance, they read that we must not be troubled when men speak ill of us, that we are to be then more pleased than when they speak well of us; that we must despise our own good name, be detached from our kindred . . . with many other things of the same kind. The disposition to practice this must be, in my opinion, the gift of God; for it seems to me a supernatural good.”47 By this statement the saint means that they are due to a special inspiration of the Holy Ghost, like the prayers which she calls “supernatural” or infused.

For these different reasons the contemporary authors whom we quoted above reject the absolute distinction and separation between ascetical and mystical theology that was introduced in the eighteenth century.

It is important to note here that the division of a science or of one of the branches of theology is not a matter of slight importance. This may be seen by the division of moral theology, which is notably different as it is made according to the distinction of the precepts of the decalogue, or according to the distinction of the theological and moral virtues. If moral theology is divided according to the precepts of the decalogue, several of which are negative, more insistence is placed on sins to be avoided than on virtues to be practiced more and more perfectly; and often the grandeur of the supreme precept of the love of God and of one’s neighbor, which dominates the decalogue and which ought to be as the soul of our life, no longer stands forth clearly enough. On the contrary, if moral theology is divided according to the distinction of the virtues, then all the elevation of the theological virtues will be evident, especially that of charity over all the moral virtues, which it should inspire and animate. If this division is made, the quickening impulse of the theological virtues is felt, especially when they are accompanied by the special inspirations of the Holy Ghost. Moral theology thus conceived develops normally into mystical theology, which is, as we see in the work of St. Francis de Sales, a simple development of the treatise on the love of God.

What, then, is ascetical theology for the contemporary theologians who return to the traditional division? According to the principles of St. Thomas Aquinas, the doctrine of St. John of the Cross and also of St. Francis de Sales, ascetical theology treats of the purgative way of beginners who, understanding that they should not remain retarded and tepid souls, exercise themselves generously in the practice of the virtues, but still according to the human mode of the virtues, ex industria propria, with the help of ordinary actual grace. Mystical theology, on the contrary, begins with the illuminative way, in which proficients, under the illumination of the Holy Ghost, already act in a rather frequent and manifest manner according to the superhuman mode of the gifts of the Holy Ghost.48 Under the special inspiration of the interior Master, they no longer act ex industria propria, but the superhuman mode of the gifts, latent until now or only occasionally patent, becomes quite manifest and frequent.

According to these authors, the mystical life is not essentially extraordinary, like visions and revelations, but something eminent in the normal way of sanctity. They consider this true even for souls called to sanctify themselves in the active life, such as a St. Vincent de Paul. They do not at all doubt that the saints of the active life have had normally rather frequent infused contemplation of the mysteries of the redeeming Incarnation, of the Mass, of the mystical body of Christ, of the value of eternal life, although these saints differ from pure contemplatives in this respect, that their infused contemplation is more immediately ordained to action, to all the works of mercy.

It follows that mystical theology is useful not alone for the direction of some souls led by extraordinary ways, but also for the direction of all interior souls who do not wish to remain retarded, who tend generously toward perfection, and who endeavor to maintain union with God in the midst of the labors and contradictions of everyday life. From this point of view, a spiritual director’s ignorance of mystical theology may become a serious obstacle for the souls he directs, as St. John of the Cross remarks in the prologue of The Ascent of Mount Carmel. If the sadness of the neurasthenic should not be taken for the passive purification of the senses, neither should melancholy be diagnosed when the passive purification does appear.

From what we have just said, it is evident that ascetical theology is ordained to mystical theology.

In short, for all Catholic authors, mystical theology which does not presuppose serious asceticism is false. Such was that of the quietists, who, like Molinos, suppressed ascetical theology by thrusting themselves into the mystical way before receiving that grace, confounding acquired passivity, which is obtained by the cessation of acts, of activity, and which turns to somnolence, with infused passivity, which springs from the special inspiration of the Holy Ghost to which the gifts render us docile. By this radical confusion, the quietism of Molinos suppressed asceticism and developed into a caricature of true mysticism.

Lastly, it is of prime importance to remark that the normal way of sanctity may be judged from two very different points of view. We may judge it by taking our nature as a starting point, and then the position that we defend as traditional will seem exaggerated. We may also judge it by taking as a starting point the supernatural mysteries of the indwelling of the Blessed Trinity, the redeeming Incarnation, and the Blessed Eucharist. This manner of judging per altissimam causam is the only one that represents the judgment of wisdom; the other manner judges by the lowest cause, and we know how “spiritual folly,” which St. Thomas speaks of, is contrary to wisdom.49

If the Blessed Trinity truly dwells in us, if the Word actually was made flesh, died for us, is really present in the Holy Eucharist, offers Himself sacramentally for us every day in the Mass, gives Himself to us as food, if all this is true, then only the saints are fully in order, for they live by this divine presence through frequent, quasiexperimental knowledge and through an ever-growing love in the midst of the obscurities and difficulties of life. And the life of close union with God, far from appearing in its essential quality as something intrinsically extraordinary, appears alone as fully normal. Before reaching such a union, we are like people still half-asleep, who do not truly live sufficiently by the immense treasure given to us and by the continually new graces granted to those who wish to follow our Lord generously.

By sanctity we understand close union with God, that is, a great perfection of the love of God and neighbor, a perfection which nevertheless always remains in the normal way, for the precept of love has no limits.50 To be more exact, we shall say that the sanctity in question here is the normal, immediate prelude of the life of heaven, a prelude which is realized, either on earth before death, or in purgatory, and which assumes that the soul is fully purified, is capable of receiving the beatific vision immediately. This is the meaning of the words “prelude of eternal life” used in the title of this work.

When we say, in short, that infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith is necessary for sanctity, we mean morally necessary; that is, in the majority of cases a soul could not reach sanctity without it. We shall add that without it a soul will not in reality possess the full perfection of Christian life, which implies the eminent exercise of the theological virtues and of the gifts of the Holy Ghost which accompany them. The purpose of this book is to establish this thesis.

Following what we have said, we shall divide this book into five parts:

1. The sources of the interior life and its end.

The life of grace, the indwelling of the Blessed Trinity, the influence of Christ the Mediator and of Mary Mediatrix on us. Christian perfection, to which the interior life is ordained, and the obligation of each individual to tend to it according to his condition.

II. The purification of the soul in beginners.

The removal of obstacles, the struggle against sin and its results, and against the predominant fault; the active purification of the senses, of the memory, the will, and the understanding. The use of the sacraments for the purification of the soul. The prayer of beginners. The second conversion or passive purification of the senses in order to enter the illuminative way of proficients.

III. The progress of the soul under the light of the Holy Ghost.

The spiritual age of proficients. The progress of the theological and moral virtues. The gifts of the Holy Ghost in proficients. The progressive illumination of the soul by the Sacrifice of the Mass and Holy Communion. The contemplative prayer of proficients. Questions relating to infused contemplation: its nature, its degrees; the call to contemplation; the direction of souls in this connection.

IV. The union of perfect souls with God.

The entrance into this way by the passive purification of the soul. The spiritual age of the perfect. The heroic degree of the theological and moral virtues. Perfect apostolic life and infused contemplation. The life of reparation. The transforming union. The perfection of love in its relation to infused contemplation, to the spiritual espousals and spiritual marriage.

V. Extraordinary graces.

The graces gratis datae. How they differ from the seven gifts of the Holy Ghost, according to St. Thomas. Application of this doctrine to extraordinary graces, according to the teaching of St. John of the Cross. Divine revelations: interior words, the stigmata, and ecstasy.

Conclusion. Reply to the question: Is the infused contemplation of the mysteries of faith and the union with God which results from it an essentially extraordinary grace, or is it in the normal way of sanctity? Is it the normal prelude to eternal life, to the beatific vision to which all souls are called?

We could discuss here the terminology used by the mystics as compared with that used by theologians. The question is of great importance. Its meaning and its import will, however, be better grasped later on, that is, at the beginning of the part of this work that deals with the illuminative way.

We could also at the end of this introduction set forth in general terms what the fathers and the great doctors of the Church teach us in the domain of spirituality. It will, however, be more profitable to do so at the end of the first part of this work when we treat of the traditional doctrine of the three ways and of the manner in which it should be understood.

Moreover, we have elsewhere set forth this teaching and that of different schools of spirituality.51 On this point Monsignor Saudreau’s work, La vie d’union a Dieu et les moyens d’y arriver d’apres les grands mattres de la spiritualite,52 may be consulted with profit. It will be well also to read Father Pourrat’s study, La spiritualite chretienne. This work is conceived from a point of view opposed to the book mentioned above, for it considers every essentially mystical grace as extraordinary. We recommend particularly the excellent work of Father Cayre, A.A., Precis de patrologie,53 in which he sets forth with great care and in a very objective manner the spiritual doctrine of the fathers and of the great doctors of the Church, including St. John of the Cross and St. Francis de Sales.54

PART 1—The Sources of the Interior Life and Its End

PROLOGUE

Since the interior life is an increasingly conscious form of the life of grace in every generous soul, we shall first of all discuss the life of grace to see its value clearly. We shall then see the nature of the spiritual organism of the infused virtues and of the gifts of the Holy Ghost, which spring from sanctifying grace in every just soul. We shall thus be led to speak of the indwelling of the Blessed Trinity in the souls of the just, and also of the continual influence exercised on them by our Lord Jesus Christ, universal Mediator, and by Mary, Mediatrix of all graces.

Such are the very elevated sources of the interior life; in their loftiness they resemble the high mountain sources of great rivers. Because our interior life descends to us from on high, it can reascend even to God and lead us to a very close union with Him. After speaking, in this first part, of the sources of interior life, we shall treat of its end, that is, of Christian perfection to which it is directed, and of everyone’s obligation to tend toward it, according to his condition. In all things the end should be considered first; for it is first in the order of intention, although it may be last in the order of execution. The end is desired first of all, even though it is last to be obtained. For this reason our Lord began His preaching by speaking of the beatitudes, and for this reason also moral theology begins with the treatise on the last end to which all our acts must be directed.

Chapter 1: The Life of Grace, Eternal life begun

The interior life of a Christian presupposes the state of grace, which is opposed to the state of mortal sin. In the present plan of Providence every soul is either in the state of grace or in the state of mortal sin; in other words, it is either turned toward God, its supernatural last end, or turned away from Him. No man is in a purely natural state, for all are called to the supernatural end, which consists in the immediate vision of God and the love which results from that vision. From the moment of creation, man was destined for this supreme end. It is to this end that we are led by Christ who, after the Fall, offered Himself as a victim for the salvation of all men.

To have a true interior life it is doubtless not sufficient to be in the state of grace, like a child after baptism or every penitent after the absolution of his sins. The interior life requires further a struggle against everything that inclines us to fall back into sin, a serious propensity of the soul toward God. If we had a profound knowledge of the state of grace, we would see that it is not only the principle of a true and very holy interior life, but that it is the germ of eternal life. We think that insistence on this point from the outset is important, recalling the words of St. Thomas: “The good of grace in one is greater than the good of nature in the whole universe”;55 for grace is the germ of eternal life, incomparably superior to the natural life of our soul or to that of the angels.

This fact best shows us the value of sanctifying grace, which we received in baptism and which absolution restores to us if we have had the misfortune to lose it.56

The value of a seed can be known only if we have some idea of what should grow from it; for example, in the order of nature, to know the value of the seed contained in an acorn, we must have seen a fully developed oak. In the human order, to know the value of the rational soul which still slumbers in a little child, we must know the normal possibilities of the human soul in a man who has reached his full development. Likewise, we cannot know the value of sanctifying grace, which is in the soul of every baptized infant and in all the just, unless we have considered, at least imperfectly, what the full development of this grace will be in the life of eternity. Moreover, it should be seen in the very light of the Savior’s words, for they are “spirit and life” and are more savory than any commentary. The language of the Gospel, the style used by our Lord, lead us more directly to contemplation than the technical language of the surest and loftiest theology. Nothing is more salutary than to breathe the pure air of these heights from which flow down the living waters of the stream of Christian doctrine.

ETERNAL LIFE PROMISED BY THE SAVIOR TO MEN OF GOOD WILL

The expression “eternal life” rarely occurs in the Old Testament, where the recompense of the just after death is often presented in a symbolical manner under the figure, for example, of the Promised Land. The rare occurrence of the expression is more easily understood when we remember that after death the just of the Old Testament had to wait for the accomplishment of the passion of the Savior and the sacrifice of the cross to see the gates of heaven opened. Everything in the Old Testament was directed primarily to the coming of the promised Savior.

In the preaching of Jesus, everything is directed immediately toward eternal life. If we are attentive to His words, we shall see how the life of eternity differs from the future life spoken of by the best philosophers, such as Plato. The future life they spoke of belonged, in their opinion, to the natural order; they though it “a fine risk to run,”57 without having absolute certltude about it. On the other hand, the Savior speaks with the most absolute assurance not only of a future life, but of eternal life superior to the past, the present, and the future; an entirely supernatural life, measured like the intimate life of God, of which it is the participation, by the single instant of immobile eternity.

Christ tells us that the way leading to eternal life is narrow,58 and that to obtain that life we must turn away from sin and keep the commandments of God.59 On several occasions He says in the Fourth Gospel: “He who heareth My word and believeth Him that sent Me, hath life everlasting,”60 that is, he who believes in Me, the Son of God, with a living faith united to charity, to the practice of the precepts, that man has eternal life begun. Christ also affirms this in the eight beatitudes as soon as He begins to preach: “Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. . . . Blessed are they that hunger and thirst after justice: for they shall have their fill. . . . Blessed are the clean of heart: for they shall see God.”61 What is eternal life, then, if not this repletion, this vision of God in His kingdom? In particular to those who suffer persecution for justice’ sake is it said: “Be glad and rejoice, for your reward is very great in heaven.”62 Before His passion Jesus says even more clearly, as St. John records: “Father, the hour is come. Glorify Thy Son that Thy Son may glorify Thee. As Thou hast given Him power over all flesh, that He may give eternal life to all whom Thou hast given Him. Now this is eternal life: that they may know Thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom Thou hast sent.”63

St. John the Evangelist himself explains these words of the Savior when he writes: “Dearly beloved, we are now the sons of God; and it hath not yet appeared what we shall be. We know that when He shall appear we shall be like to Him: because we shall see Him as He is.”64 We shall see Him as He is, and not only by the reflection of His perfections in creatures, in sensible nature, or in the souls of the saints, in their words and their acts; we shall see Him immediately as He is in Himself.

St. Paul adds: “We see (God) now through a glass in a dark manner; but then face to face. Now I know in part; but then I shall know even as I am known.”65 Observe that St. Paul does not say that I shall know Him as I know myself, as I know the interior of my conscience. I certainly know the interior of my soul better than other men do; but it has secrets from me, for I cannot measure all the gravity of my directly or indirectly voluntary faults. God alone knows me thoroughly; the secrets of my heart are perfectly open only to His gaze.