G. K. Chesterton

1904 by Macmillan and Co., London, UK.

This

work is published for the greater Glory of Jesus Christ through His

most

Holy Mother Mary and for the sanctification of the militant

Church and her members.

PUBLISHER

INDEX

THE BLATCHFORD CONTROVERSIES

Introduction by Masie Ward

Against R. J. Campbell [Chesterton] showed in a lecture on “Christianity and Social Reform” how belief in sin as well as in goodness was more favourable to social reform than was the rather woolly optimism that refused to recognize evil. “The nigger–driver will be delighted to hear that God is immanent in him . . . The sweater that . . . he has not in any way become divided from the supreme perfection of the universe.” If the New Theology would not lead to social reform, the social Utopia to which the philosophy of [H. G.] Wells and of [George Bernard] Shaw was pointing seemed to Chesterton not a heaven on earth to be desired, but a kind of final hell to be avoided, since it banished all freedom and human responsibility. Arguing with them was again highly fruitful, and two subjects he chose for speeches are suggestive–”The Terror of Tendencies” and “Shall We Abolish the Inevitable?”

In the New Age Shaw wrote about Belloc and Chesterton and so did Wells, while Chesterton wrote about Wells and Shaw, till the Philistines grew angry, called it self–advertisement and log–rolling and urged that a Bill for the abolition of Shaw and Chesterton should be introduced into Parliament. But G.K. had no need for advertisement of himself or his ideas just then: he had a platform, he had an eager audience. Every week he wrote in the Illustrated London News, beginning in 1905 to do “Our Notebook” (this continued till his death in 1936). He was still writing every Saturday in the Daily News. Publishers were disputing for each of his books. Yet he rushed into every religious controversy that was going on, because thereby he could clarify and develop his ideas.

The most important of all these was the controversy with Blatchford, Editor of the Clarion, who had written a rationalist Credo, entitled God and My Neighbour. In 1903–4, he had the generosity and the wisdom to throw open the Clarion to the freest possible discussion of his views. The Christian attack was made by a group of which Chesterton was the outstanding figure, and was afterwards gathered into a paper volume called The Doubts of Democracy.

One essay in this volume, written in 1903, is of primary importance in any study of the sources of Orthodoxy, for it gives a brilliant outline of one of the main contentions of the book and shows even better than Orthodoxy itself what he meant by saying that he had first learnt Christianity from its opponents. It is clear that by now he believed in the Divinity of Christ. The pamphlet itself has fallen into oblivion and Chesterton’s share of it was only three short essays. . . . in [them] he has put in concentrated form and with different illustrations what he developed five years later. There is nothing more packed with thought in the whole of his writings than these essays.

1. Christianity and Rationalism

The first of all the difficulties that I have in controverting Mr. Blatchford is simply this, that I shall be very largely going over his own ground. My favourite text–book of theology is [Blatchford’s] God and My Neighbour, but I cannot repeat it in detail. If I gave each of my reasons for being a Christian, a vast number of them would be Mr. Blatchford’s reasons for not being one.

For instance, Mr. Blatchford and his school point out that there are many myths parallel to the Christian story; that there were Pagan Christs, and Red Indian Incarnations, and Patagonian Crucifixions, for all I know or care. But does not Mr. Blatchford see the other side of the fact? If the Christian God really made the human race, would not the human race tend to rumours and perversions of the Christian God? If the centre of our life is a certain fact, would not people far from the centre have a muddled version of that fact? If we are so made that a Son of God must deliver us, is it odd that Patagonians should dream of a Son of God?

The Blatchfordian position really amounts to this—that because a certain thing has impressed millions of different people as likely or necessary, therefore it cannot be true. And then this bashful being, veiling his own talents, convicts the wretched G.K.C. of paradox. I like paradox, but I am not prepared to dance and dazzle to the extent of Nunquam, who points to humanity crying out for a thing, and pointing to it from immemorial ages, as proof that it cannot be there.

The story of a Christ is very common in legend and literature. So is the story of two lovers parted by Fate. So is the story of two friends killing each other for a woman. But will it seriously be maintained that, because these two stories are common as legends, therefore no two friends were ever separated by love or no two lovers by circumstances? It is tolerably plain, surely, that these two stories are common because the situation is an intensely probable and human one, because our nature is so built as to make them almost inevitable.

Why should it not be that our nature is so built as to make certain spiritual events inevitable? In any case, it is clearly ridiculous to attempt to disprove Christianity by the number and variety of Pagan Christs. You might as well take the number and variety of ideal schemes of society, from Plato’s Republic to Morris’ News from Nowhere, from More’s Utopia to Blatchford’s Merrie England, and then try to prove from them that mankind cannot ever reach a better social condition. If anything, of course, they prove the opposite; they suggest a human tendency toward a better condition.

Thus, in this first instance, when learned sceptics come to me and say, “Are you aware that the Kaffirs have a sort of Incarnation?” I should reply: “Speaking as an unlearned person, I don’t know. But speaking as a Christian, I should be very much astonished if they hadn’t.”

Take a second instance. The Secularist says that Christianity has been a gloomy and ascetic thing, and points to the procession of austere or ferocious saints who have given up home and happiness and macerated health and sex. But it never seems to occur to him that the very oddity and completeness of these men’s surrender make it look very much as if there were really something actual and solid in the thing for which they sold themselves. They gave up all pleasures for one pleasure of spiritual ecstasy. They may have been mad; but it looks as if there really were such a pleasure. They gave up all human experiences for the sake of one superhuman experience. They may have been wicked, but it looks as if there were such an experience.

It is perfectly tenable that this experience is as dangerous and selfish a thing as drink. A man who goes ragged and homeless in order to see visions may be as repellant and immoral as a man who goes ragged and homeless in order to drink brandy. That is a quite reasonable position. But what is manifestly not a reasonable position, what would be, in fact, not far from being an insane position, would be to say that the raggedness of the man, and the stupefied degradation of the man, proved that there was no such thing as brandy. That is precisely what the Secularist tries to say. He tries to prove that there is no such thing as supernatural experience by pointing at the people who have given up everything for it. He tries to prove that there is no such thing by proving that there are people who live on nothing else.

Again I may submissively ask: “Whose is the Paradox?” The fanatic severity of these men may, of course, show that they were eccentric people who loved unhappiness for its own sake. But it seems more in accordance with common sense to suppose that they had really found the secret of some actual power or experience which was, like wine, a terrible consolation and a lonely joy.

Thus, then in the second instance, when the learned sceptic says to me: “Christian saints gave up love and liberty for this one rapture of Christianity,” I should reply: “It was very wrong of them. But, having some notion of the rapture of Christianity, I should have been surprised if they hadn’t.”

Take a third instance. The Secularist says that Christianity produced tumult and cruelty. He seems to suppose that this proves it to be bad. But it might prove it to be very good. For men commit crimes not only for bad things, far more often for good things. For no bad things can be desired quite so passionately and persistently as good things can be desired, and only very exceptional men desire very bad and unnatural things.

Most crime is committed because, owing to some peculiar complication, very beautiful or necessary things are in some danger . . .

And if anywhere in history masses of common and kindly men become cruel, it almost certainly does not mean that they are serving something in itself tyrannical (for why should they?). It almost certainly does mean that something that they rightly value is in peril, such as the food of their children, the chastity of their women, or the independence of their country. And when something is set before mankind that is not only enormously valuable, but also quite new, the sudden vision, the chance of winning it, the chance of losing it, drive them mad. It has the same effect in the moral world that the finding of gold has in the economic world. It upsets values, and creates a kind of cruel rush.

We need not go far for instances quite apart from the instances of religion. When the modern doctrines of brotherhood and liberality were preached in France in the eighteenth century the time was ripe for them, the educated classes everywhere had been growing towards them, the world to a very considerable extent welcomed them. And yet all that preparation and openness were unable to prevent the burst of anger and agony which greets anything good. And if the slow and polite preaching of rational fraternity in a rational age ended in the massacres of September, what an a fortiori is here! What would be likely to be the effect of the sudden dropping into a dreadfully evil century of a dreadfully perfect truth? What would happen if a world baser than the world of Sade were confronted with a gospel purer than the gospel of Rousseau?

The mere flinging of the polished pebble of Republican idealism into the artificial lake of eighteenth century Europe produced a splash that seemed to splash the heavens, and a storm that drowned ten thousand men. What would happen if a star from heaven really fell into the slimy and bloody pool of a hopeless and decaying humanity? Men swept a city with the guillotine, a continent with a sabre, because Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity were too precious to be lost. How if Christianity was yet more maddening because it was yet more precious?

But why should we labour the point when One who knew human nature as it can really be learnt, from fishermen and women and natural people, saw from his quiet village the track of this truth across history, and, in saying that He came to bring not peace but a sword, set up eternally His colossal realism against the eternal sentimentality of the Secularist?

Thus, then, in the third instance, when the learned sceptic says: “Christianity produced wars and persecutions,” we shall reply: “Naturally.”

And, lastly, let me take an example which leads me on directly to the general matter I wish to discuss for the remaining space of the articles at my command. The Secularist constantly points out that the Hebrew and Christian religions began as local things; that their god was a tribal god; that they gave him material form, and attached him to particular places.

This is an excellent example of one of the things that if I were conducting a detailed campaign I should use as an argument for the validity of Biblical experience. For if there really are some other and higher beings than ourselves, and if they in some strange way, at some emotional crisis, really revealed themselves to rude poets or dreamers in very simple times, that these rude people should regard the revelation as local, and connect it with the particular hill or river where it happened, seems to me exactly what any reasonable human being would expect. It has a far more credible look than if they had talked cosmic philosophy from the beginning. If they had, I should have suspected “priestcraft” and forgeries and third–century gnosticism.

If there be such a being as God, and He can speak to a child, and if God spoke to a child in the garden, the child would, of course, say that God lived in the garden. I should not think it any less likely to be true for that. If the child said: “God is everywhere; an impalpable essence pervading and supporting all constituents of the Cosmos alike”–if, I say, the infant addressed me in the above terms, I should think he was much more likely to have been with the governess than with God.

So if Moses had said God was an Infinite Energy, I should be certain he had seen nothing extraordinary. As he said He was a Burning Bush, I think it very likely that he did see something extraordinary. For whatever be the Divine Secret, and whether or no it has (as all people have believed) sometimes broken bounds and surged into our world, at least it lies on the side furthest away from pedants and their definitions, and nearest to the silver souls of quiet people, to the beauty of bushes, and the love of one’s native place.

Thus, then, in our last instance (out of hundreds that might be taken), we conclude in the same way. When the learned sceptic says: “The visions of the Old Testament were local, and rustic, and grotesque,” we shall answer: “Of course. They were genuine.”

Thus, as I said at the beginning, I find myself, to start with, face to face with the difficulty that to mention the reasons that I have for believing in Christianity is, in very many cases, simply to repeat those arguments which Mr. Blatchford, in some strange way, seems to regard as arguments against it. His book is really rich and powerful. He has undoubtedly set up these four great guns of which I have spoken. I have nothing to say against the size and ammunition of the guns. I only say that by some strange accident of arrangement he has set up those four pieces of artillery pointing at himself. If I were not so humane, I should say: “Gentlemen of the Secularist Guard, fire first.”

2. Why I Believe in Christianity

I mean no disrespect to Mr. Blatchford in saying that our difficulty very largely lies in the fact that he, like masses of clever people nowadays, does not understand what theology is. To make mistakes in a science is one thing, to mistake its nature another. And as I read God and My Neighbour, the conviction gradually dawns on me that he thinks theology is the study of whether a lot of tales about God told in the Bible are historically demonstrable. This is as if he were trying to prove to a man that Socialism was sound Political Economy, and began to realise half–way through that the man thought that Political Economy meant the study of whether politicians were economical.

It is very hard to explain briefly the nature of a whole living study; it would be just as hard to explain politics or ethics. For the more a thing is huge and obvious and stares one in the face, the harder it is to define. Anybody can define conchology. Nobody can define morals.

Nevertheless it falls to us to make some attempt to explain this religious philosophy which was, and will be again, the study of the highest intellects and the foundation of the strongest nations, but which our little civilisation has for a while forgotten, just as it has forgotten how to dance and how to dress itself decently. I will try and explain why I think a religious philosophy necessary and why I think Christianity the best religious philosophy. But before I do so I want you to bear in mind two historical facts. I do not ask you to draw my deduction from them or any deduction from them. I ask you to remember them as mere facts throughout the discussion.

1. Christianity arose and spread in a very cultured and very cynical world–in a very modern world. Lucretius was as much a materialist as Haeckel, and a much more persuasive writer. The Roman world had read God and My Neighbour, and in a weary sort of way thought it quite true. It is worth noting that religions almost always do arise out of these sceptical civilisations. A recent book on the Pre–Mohammedan literature of Arabia describes a life entirely polished and luxurious. It was so with Buddha, born in the purple of an ancient civilisation. It was so with Puritanism in England and the Catholic Revival in France and Italy, both of which were born out of the rationalism of the Renaissance. It is so to–day; it is always so. Go to the two most modern and free–thinking centres, Paris and America, and you will find them full of devils and angels, of old mysteries and new prophets. Rationalism is fighting for its life against the young and vigorous superstitions.

2. Christianity, which is a very mystical religion, has nevertheless been the religion of the most practical section of mankind. It has far more paradoxes than the Eastern philosophies, but it also builds far better roads.

The Moslem has a pure and logical conception of God, the one Monistic Allah. But he remains a barbarian in Europe, and the grass will not grow where he sets his foot. The Christian has a Triune God, “a tangled trinity,” which seems a mere capricious contradiction in terms. But in action he bestrides the earth, and even the cleverest Eastern can only fight him by imitating him first. The East has logic and lives on rice. Christendom has mysteries–and motor cars. Never mind, as I say, about the inference, let us register the fact.

Now with these two things in mind let me try and explain what Christian theology is.

Complete Agnosticism is the obvious attitude for man. We are all Agnostics until we discover that Agnosticism will not work. Then we adopt some philosophy, Mr. Blatchford’s or mine or some others, for of course Mr. Blatchford is no more an Agnostic than I am. The Agnostic would say that he did not know whether man was responsible for his sins. Mr. Blatchford says that he knows that man is not.

Here we have the seed of the whole huge tree of dogma. Why does Mr. Blatchford go beyond Agnosticism and assert that there is certainly no free will? Because he cannot run his scheme of morals without asserting that there is no free will. He wishes no man to be blamed for sin. Therefore he has to make his disciples quite certain that God did not make them free and therefore blamable. No wild Christian doubt must flit through the mind of the Determinist. No demon must whisper to him in some hour of anger that perhaps the company promoter was responsible for swindling him into the workhouse. No sudden scepticism must suggest to him that perhaps the schoolmaster was blamable for flogging a little boy to death. The Determinist faith must be held firmly, or else certainly the weakness of human nature will lead men to be angered when they are slandered and kick back when they are kicked. In short, free will seems at first sight to belong to the Unknowable. Yet Mr. Blatchford cannot preach what seems to him common charity without asserting one dogma about it. And I cannot preach what seems to me common honesty without asserting another.

Here is the failure of Agnosticism. That our every–day view of the things we do (in the common sense) know, actually depends upon our view of the things we do not (in the common sense) know. It is all very well to tell a man, as the Agnostics do, to “cultivate his garden.” But suppose a man ignores everything outside his garden, and among them ignores the sun and the rain?

This is the real fact. You cannot live without dogmas about these things. You cannot act for twenty–four hours without deciding either to hold people responsible or not to hold them responsible. Theology is a product far more practical than chemistry.

Some Determinists fancy that Christianity invented a dogma like free will for fun—a mere contradiction. This is absurd. You have the contradiction whatever you are. Determinists tell me, with a degree of truth, that Determinism makes no difference to daily life. That means that although the Determinist knows men have no free will, yet he goes on treating them as if they had.

The difference then is very simple. The Christian puts the contradiction into his philosophy. The Determinist puts it into his daily habits. The Christian states as an avowed mystery what the Determinist calls nonsense. The Determinist has the same nonsense for breakfast, dinner, tea, and supper every day of his life.

The Christian, I repeat, puts the mystery into his philosophy. That mystery by its darkness enlightens all things. Once grant him that, and life is life, and bread is bread, and cheese is cheese: he can laugh and fight. The Determinist makes the matter of the will logical and lucid: and in the light of that lucidity all things are darkened, words have no meaning, actions no aim. He has made his philosophy a syllogism and himself a gibbering lunatic.

It is not a question between mysticism and rationality. It is a question between mysticism and madness. For mysticism, and mysticism alone, has kept men sane from the beginning of the world. All the straight roads of logic lead to some Bedlam, to Anarchism or to passive obedience, to treating the universe as a clockwork of matter or else as a delusion of mind. It is only the Mystic, the man who accepts the contradictions, who can laugh and walk easily through the world.

Are you surprised that the same civilisation which believed in the Trinity discovered steam?

All the great Christian doctrines are of this kind. Look at them carefully and fairly for yourselves. I have only space for two examples. The first is the Christian idea of God. Just as we have all been Agnostics so we have all been Pantheists. In the godhood of youth it seems so easy to say, “Why cannot a man see God in a bird flying and be content?” But then comes a time when we go on and say, “If God is in the birds, let us be not only as beautiful as the birds; let us be as cruel as the birds; let us live the mad, red life of nature.” And something that is wholesome in us resists and says, “My friend, you are going mad.”

Then comes the other side and we say: “The birds are hateful, the flowers are shameful. I will give no praise to so base an universe.” And the wholesome thing in us says: “My friend, you are going mad.”

Then comes a fantastic thing and says to us: “You are right to enjoy the birds, but wicked to copy them. There is a good thing behind all these things, yet all these things are lower than you. The Universe is right: but the World is wicked. The thing behind all is not cruel, like a bird: but good, like a man.” And the wholesome thing in us says. “I have found the high road.”

Now when Christianity came, the ancient world had just reached this dilemma. It heard the Voice of Nature–Worship crying, “All natural things are good. War is as healthy as he flowers. Lust is as clean as the stars.” And it heard also the cry of the hopeless Stoics and Idealists: “The flowers are at war: the stars are unclean: nothing but man’s conscience is right and that is utterly defeated.”

Both views were consistent, philosophical and exalted: their only disadvantage was that the first leads logically to murder and the second to suicide. After an agony of thought the world saw the sane path between the two. It was the Christian God. He made Nature but He was Man.

Lastly, there is a word to be said about the Fall [Original Sin]. It can only be a word, and it is this. Without the doctrine of the Fall all idea of progress is unmeaning. Mr. Blatchford says that there was not a Fall but a gradual rise. But the very word “rise” implies that you know toward what you are rising. Unless there is a standard you cannot tell whether you are rising or falling. But the main point is that the Fall like every other large path of Christianity is embodied in the common language talked on the top of an omnibus. Anybody might say, “Very few men are really Manly.” Nobody would say, “Very few whales are really whaley.”

If you wanted to dissuade a man from drinking his tenth whisky you would slap him on the back and say, “Be a man.” No one who wished to dissuade a crocodile from eating his tenth explorer would slap it on the back and say, “Be a crocodile.” For we have no notion of a perfect crocodile; no allegory of a whale expelled from his whaley Eden. If a whale came up to us and said: “I am a new kind of whale; I have abandoned whalebone,” we should not trouble. But if a man came up to us (as many will soon come up to us) to say, “I am a new kind of man. I am the super–man. I have abandoned mercy and justice”; we should answer, “Doubtless you are new, but you are not nearer to the perfect man, for he has been already in the mind of God. We have fallen with Adam and we shall rise with Christ; but we would rather fall with Satan than rise with you.”

3. Miracles and Modern Civilisation

Mr. Blatchford has summed up all that is important in his whole position in three sentences. They are perfectly honest and clear. Nor are they any the less honest and clear because the first two of them are falsehoods and the third is a fallacy. He says “The Christian denies the miracles of the Mahommedan. The Mahommedan denies the miracles of the Christian. The Rationalist denies all miracles alike.”

The historical error in the first two remarks I will deal with shortly. I confine myself for the moment to the courageous admission of Mr. Blatchford that the Rationalist denies all miracles alike. He does not question them. He does not pretend to be agnostic about them. He does not suspend his judgment until they shall be proved. He denies them. Faced with this astounding dogma I asked Mr. Blatchford why he thought miracles would not occur. He replied that the Universe was governed by laws. Obviously this answer is of no use whatever. For we cannot call a thing impossible because the world is governed by laws, unless we know what laws. Does Mr. Blatchford know all about all the laws in the Universe? And if he does not know about the laws how can he possibly know anything about the exceptions?

For, obviously, the mere fact that a thing happens seldom, under odd circumstances and with no explanation within our knowledge, is no proof that it is against natural law. That would apply to the Siamese twins, or to a new comet, or to radium three years ago.

The philosophical case against miracles is somewhat easily dealt with. There is no philosophical case against miracles. There are such things as the laws of Nature rationally speaking. What everybody knows is this only. That there is repetition in nature. What everybody knows is that pumpkins produce pumpkins. What nobody knows is why they should not produce elephants and giraffes.

There is one philosophical question about miracles and only one. Many able modern Rationalists cannot apparently even get it into their heads. The poorest lad at Oxford in the Middle Ages would have understood it. (Note. As the last sentence will seem strange in our “enlightened” age I may explain that under “the cruel reign of mediaeval superstition,” poor lads were educated at Oxford to a most reckless extent. Thank God, we live in better days.)

The question of miracles is merely this. Do you know why a pumpkin goes on being a pumpkin? If you do not, you cannot possibly tell whether a pumpkin could turn into a coach or couldn’t. That is all.

All the other scientific expressions you are in the habit of using at breakfast are words and winds. You say “It is a law of nature that pumpkins should remain pumpkins.” That only means that pumpkins generally do remain pumpkins, which is obvious; it does not say why. You say “Experience is against it.” That only means, “I have known many pumpkins intimately and none of them turned into coaches.”

There was a great Irish Rationalist of this school (possibly related to Mr. Lecky), who when he was told that a witness had seen him commit murder said that he could bring a hundred witnesses who had not seen him commit it.

You say “The modern world is against it.” That means that a mob of men in London and Birmingham, and Chicago, in a thoroughly pumpkiny state of mind, cannot work miracles by faith.

You say “Science is against it.” That means that so long as pumpkins are pumpkins their conduct is pumpkiny, and bears no resemblance to the conduct of a coach. That is fairly obvious.

What Christianity says is merely this. That this repetition in Nature has its origin not in a thing resembling a law but a thing resembling a will. Of course its phrase of a Heavenly Father is drawn from an earthly father. Quite equally Mr. Blatchford’s phrase of a universal law is a metaphor from an Act of Parliament. But Christianity holds that the world and its repetition came by will or Love as children are begotten by a father, and therefore that other and different things might come by it. Briefly, it believes that a God who could do anything so extraordinary as making pumpkins go on being pumpkins, is like the prophet, Habbakuk, Capable de tout. If you do not think it extraordinary that a pumpkin is always a pumpkin, think again. You have not yet even begun philosophy. You have not even seen a pumpkin.

The historic case against miracles is also rather simple. It consists of calling miracles impossible, then saying that no one but a fool believes impossibilities: then declaring that there is no wise evidence on behalf of the miraculous. The whole trick is done by means of leaning alternately on the philosophical and historical objection. If we say miracles are theoretically possible, they say, “Yes, but there is no evidence for them.” When we take all the records of the human race and say, “Here is your evidence,” they say, “But these people were superstitious, they believed in impossible things.”

The real question is whether our little Oxford Street civilisation is certain to be right and the rest of the world certain to be wrong. Mr. Blatchford thinks that the materialism of nineteenth century Westerns is one of their noble discoveries. I think it is as dull as their coats, as dirty as their streets, as ugly as their trousers, and as stupid as their industrial system.

Mr. Blatchford himself, however, has summed up perfectly his pathetic faith in modern civilisation. He has written a very amusing description of how difficult it would be to persuade an English judge in a modern law court of the truth of the Resurrection. Of course he is quite right; it would be impossible. But it does not seem to occur to him that we Christians may not have such an extravagant reverence for English judges as is felt by Mr. Blatchford himself.

The experiences of the Founder of Christianity have perhaps left us in a vague doubt of the infallibility of courts of law. I know quite well that nothing would induce a British judge to believe that a man had risen from the dead. But then I know quite as well that a very little while ago nothing would have induced a British judge to believe that a Socialist could be a good man. A judge would refuse to believe in new spiritual wonders. But this would not be because he was a judge, but because he was, besides being a judge, an English gentleman, a modern Rationalist, and something of an old fool.

And Mr. Blatchford is quite wrong in supposing that the Christian and the Moslem deny each other’s miracles. No religion that thinks itself true bothers about the miracles of another religion. It denies the doctrines of the religion; it denies its morals; but it never thinks it worth while to deny its signs and wonders.

And why not? Because these things some men have always thought possible. Because any wandering gipsy may have Psychical powers. Because the general existence of a world of spirits and of strange mental powers is a part of the common sense of all mankind. The Pharisees did not dispute the miracles of Christ; they said they were worked by devilry. The Christians did not dispute the miracles of Mahomed. They said they were worked by devilry. The Roman world did not deny the possibility that Christ was a God. It was far too enlightened for that.

In so far as the Church did (chiefly during the corrupt and sceptical eighteenth century) urge miracles as a reason for belief, her fault is evident: but it is not what Mr. Blatchford supposes. It is not that she asked men to believe anything so incredible; it is that she asked men to be converted by anything so commonplace.

What matters about a religion is not whether it can work marvels like any ragged Indian conjurer, but whether it has a true philosophy of the Universe. The Romans were quite willing to admit that Christ was a God. What they denied was the He was the God—the highest truth of the cosmos. And this is the only point worth discussing about Christianity.

4. The Eternal Heroism of the Slums

I have said it before, but it cannot be too often repeated, that what is the matter with Mr. Blatchford and his school is that they are not sceptical enough. For the really bold questions we have to go back to the Christian Fathers.

For example, Mr. Blatchford, in God and My Neighbor, does me the honour to quote from me as follows: “Mr. G. K. Chesterton, in defending Christianity, said, ‘Christianity has committed crimes at which the sun might sicken in heaven, and no one can refute the statement.’ “ I did say this, and I say it again, but I said something else. I said that every great and useful institution had committed such crimes. And no one can refute that statement.

And why has every great institution been criminal? It is not enough to say “Christians persecuted; down with Christianity.” Any more than it is enough to say, “A Confucian stole my hair–brush; down with Confucianism.” We want to know whether the reason for which the Confucian stole the hair–brush was a reason peculiar to the Confucian or a reason common to many other men.

It is obvious that the Christian’s reason for torturing was a reason common to hosts of other men; it was simply the fact that he held his views strongly and tried unscrupulously to make them prevail. Any other man might hold any other views strongly and try unscrupulously to make them prevail. And when we look at the facts we find, I say, that millions of other men do, and have done so from the beginning of the world.

Mr. Blatchford quoted the one exception of Buddhism which never problem politically. This is, if ever there was one, an exception that proves the rule. For Buddhism has never persecuted, simply because it has never been political at all, because it has always despised material happiness and material civilization. That is to say, Buddhism has never had an inquisition for exactly the same reason that it has never had a printing–press, or a Reform Bill, or a Clarion newspaper.

But if Mr. Blatchford really thinks that the gory past of an institution damns it, and if he really wants an institution to damn, an institution which is much older, and much larger, and much gorier than Christianity, I can easily oblige him.

The institution called Government or the State has a past more shameful than a pirate ship. Every legal code on earth has been full of ferocity and heartrending error. The rack and the stake were not invented by Christians; Christians only picked up the horrible cast toys of Paganism. The rack and the stake were invented by a bitter Rationalism older than all religions. The rack and the stake were invented by the State, by Society, by the Social Ideal—or, to put it shortly, by Socialism. And this State or Government, the mother of all whips and thumbscrews, this is, if you please, the very thing which Mr. Blatchford and his socialistic following would make stronger than it has ever been under the sun. Strange and admirable delicacy. Delicacy which can have no further dealings with Christianity, because of the Masssacre of Saint Bartholomew, but must rather invoke to purify the world a thing which has shown its soul in the torturing of Roman slaves for evidence, and in the artistic punishments of China.

I do disagree with Mr. Blatchford for invoking the State. But then I do not think that the goriness of a thing’s past disqualifies it from saving mankind. I, therefore, am consistent in thinking that Christianity is not disqualified. But Mr. Blatchford is not consistent, for he positively appeals to the greater sinner to save him from the lesser.

If only Mr. Blatchford would ask the real question. It is not, “Why is Christianity so bad when it claims to be so good?” The real question is “Why are all human things so bad when they claim to be so good?” Why is not the most noble scheme a guarantee against corruption? If Nunquam will boldly pursue this question, will really leave delusions behind and walk across the godless waste, alone, he will come at last to a strange place. His sceptical pilgrimage will end at a place where Christianity begins.

Christianity begins with the wickedness of the Inquisition. Only it adds the wickedness of English Liberals, Tories, Socialists, and county magistrates It begins with a strange thing running across human history. This it calls Sin, or the Fall of Man.

If ever I wish to expound it further, Mr. Blatchford’s list of Christian crimes will be a more valuable compilation. In brief however, Mr. Blatchford sees the sins of historic Christianity rise before him like a great tower. It is a star–defying Tower of Babel, lifting itself alone into the sky, affronting God in Heaven. Let him climb up it for a few years. When he is near to its tremendous top, he will find that it is one of the nine hundred and ninety–nine columns which support the pedestal of the historic Christianity philosophy.

Right or wrong, Christianity has her theory and her remedy for the world’s evils. But what is Mr. Blatchford’s remedy? Before him also lies the wilderness of human frenzy and frivolity. What is his remedy? I am not uttering (as anyone ignorant of the facts might fancy) a wild joke. I am stating the sober truth of the situation, when I say that Mr. Blatchford’s remedy for all this is that nobody should be responsible for anything.

Never perhaps in the history of mankind has a serious malady been met by a more astounding cure. For Mr. Blatchford, remember, propounds it as a cure. Men have admitted Fatalism as a melancholy metaphysical truth. No one before him, as far as I know, ever took it round with a big drum as a cheery means of moral improvement. The problem is that men will not live up to ideals. The problem is that while Marcus Aurelius is breaking his heart for righteousness, his own son Commodus cares only for bloodthirsty pantomimes. The remedy is to tell Commodus that he cannot help it. The problem is that the purity of St. Francis cannot prevent the corruption of Brother Elias. The remedy is to tell Brother Elias that he is not to be blamed and Francis not to be admired. The problem is that a man will often choose a base pleasure rather than a hard generosity. The remedy is to tell him that the base pleasure has been chosen for him.

I know quite well, of course, that Mr. Blatchford tried to make this monstrous anarchy more tolerable to the intellect. He did it by saying that although people ought not to be blamed for their actions, yet they ought to be trained to do better. They ought, he said, to be given better conditions of heredity and environment, and then they would be good, and the problem would be solved. The primary answer is obvious. How can one say that a man ought not to be held responsible, but ought to be well trained? For if he “ought” to be well trained, there must be somebody who “ought” to train him. And that man must be held responsible for training him. The proposition has killed itself in three sentences. Mr. Blatchford has not removed the necessity for responsibility merely by saying that humanity, instead of being dealt with by the hangmen, ought to be dealt with by the doctors. For, upon the whole, and supposing I required the services of either, I think I would sooner be dealt with by an irresponsible hangman than by an irresponsible doctor.

The second thing to say, of course, is that Mr. Blatchford offers nothing even remotely resembling an argument to show that he knows what conditions would produce good men, or that anybody knows. He cannot surely mean that mere conditions of physical comfort and mental culture produce good men; because manifestly they do not. Mr. Blatchford may have some secret recipe for virtue, making people live in trees, or shave their heads, or dine on some peculiar kind of losenge, but he has not told anybody what it is.

The fact is very simple. It may be true that perfect conditions would produce perfect men. But it is much more obviously that only perfect men could invent perfect conditions. If we make such a mess of our own lives, how can we be certain that we know the best soil for living things? If heredity and environment make it so necessary for us to commit theft and adultery, why should they not make it necessary for us to create conditions that will lead to theft and adultery? In the British Isles at this moment there exist, I imagine, people in every conceivable degree of riches and poverety, from insane opulence to insane hunger. Is anyone of those classes morally exquisite or glaringly any better than the rest? And where so many modes of education fail, by what right does Mr. Blatchford assume his, whatever it is, to be infallible?

As for the great part of the talk of Mr. Blatchford about sin arising from vile and filthy environments, I do not wish to introduce into this discussion anything of personal emotion, but I am bound to say that I have great difficulty in enduring that talk with patience. Who in the world is it who thus speaks as if wickedness and folly raged only among the unfortunate? Is it Mr. Blatchford who falls back upon the old contemptible impertinence which represents virtue to be something upper–class, like a visiting card, or a silk hat? Is it Nunquam who denies the eternal heroism of the slums? The thing is almost incredible, but so it is. Nunquam has put a coping stone upon his Tempe, this association of vice with poverty, the vilest and the oldest and the dirtiest of all the stones that insolence has ever flung at the poor.

Man that is born of woman has short days and full of trouble; but he is a nobler and a happier being than this would make him out. I will not deign to answer even Mr. Blatchford when he asks “how” a man born in filth and sin can live a noble life. I know so many who are doing it, within a stone’s throw of my own house, in Battersea, that I care little how it is done. Man has something in him always which is not conquered by conditions. Yes, there is a liberty that has never been chained. There is a liberty that has made men happy in dungeons, as it may make then happy in slums. It is the liberty of the mind, that is to say, it is the one liberty on which Mr. Blatchford makes war. That which all the tyrrans have left, he would extinguish. That which no gaoler could ever deny to a prisoner, Nunquam would deny. More numerous than can be counted, in all the wars and persecutions of the world, men have looked out of their little grated windows and said, “at least my thoughts are free.” “No, No,” says the face of Mr. Blatchford, suddenly appearing at the window, “your thoughts are the inevitable result of heredity and environment. Your thoughts are as material as your dungeons. Your thoughts are as mechanical as the guillotine.” So pants this strange comforter, from cell to cell.

I suppose Mr. Blatchford would say that in his Utopia nobody would be in prison. What do I care whether I am in prison or no, if I have to drag chains everywhere. A man in his Utopia may have, for all I know, free food, free meadows, his own estate, his own palace. What

does it matter? he may not have his own soul. Every thought that comes into his head he must regard as the click of a machine. He sees a lost child and with a spasm of pity decides to adopt it. Click! he has to remember that he has not really done it at all. He has a temptation to do some huge irresistible sin; he reminds himself that he is a man, that he can, if he likes, be a hero; he resists it. Click! he remember that he is not a man and not a hero, but a machine, so made as to produce that result. He walks in wide fields under a splendid sunrise; he resolves on some vast magnanimity—Click! what is the good of sunrises and palaces? Was ever slavery like unto this slavery? Was ever man before so much a slave?

I know that this will never be, That is, I know that Mr. Blatchford’s philosophy will never be endured among sane men. But if ever it is I will very easily predict what will happen. Man, the machine, will stand up in these flowery meadows and cry aloud, “Was there not once a thing, a church, that taught us we were free in our souls? Did it not surround itself with tortures and dungeons in order to force men to believe that their souls were free? If there was, let it return, tortures, dungeons and all. Put me in those dungeons, rack me with those tortures, if by that means I may possibly believe it again.”

ILLUSTRATIONS

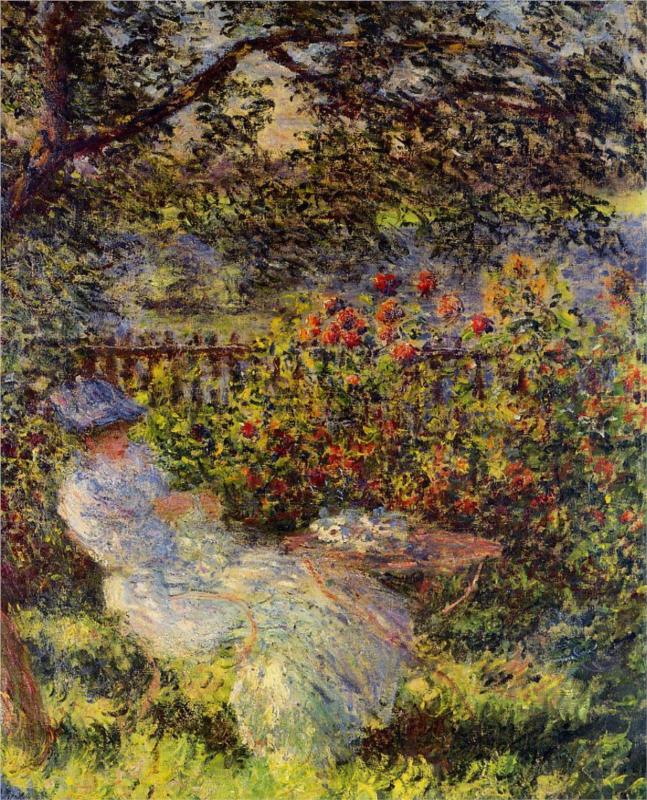

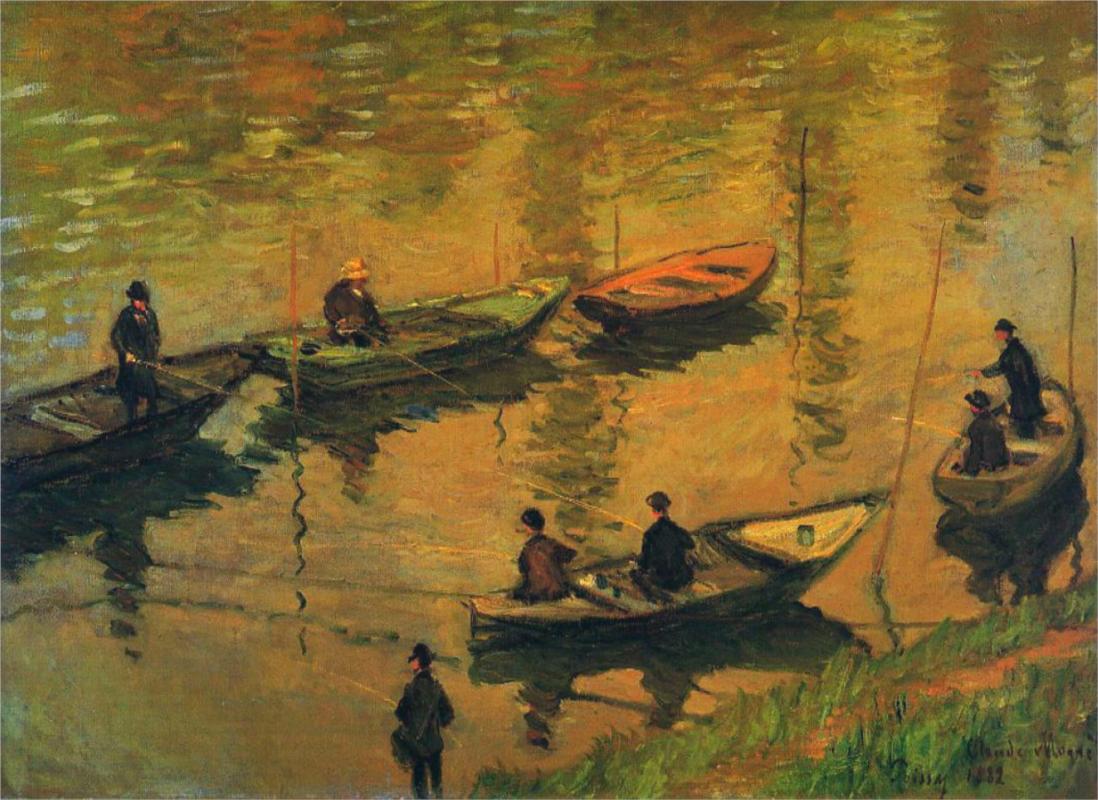

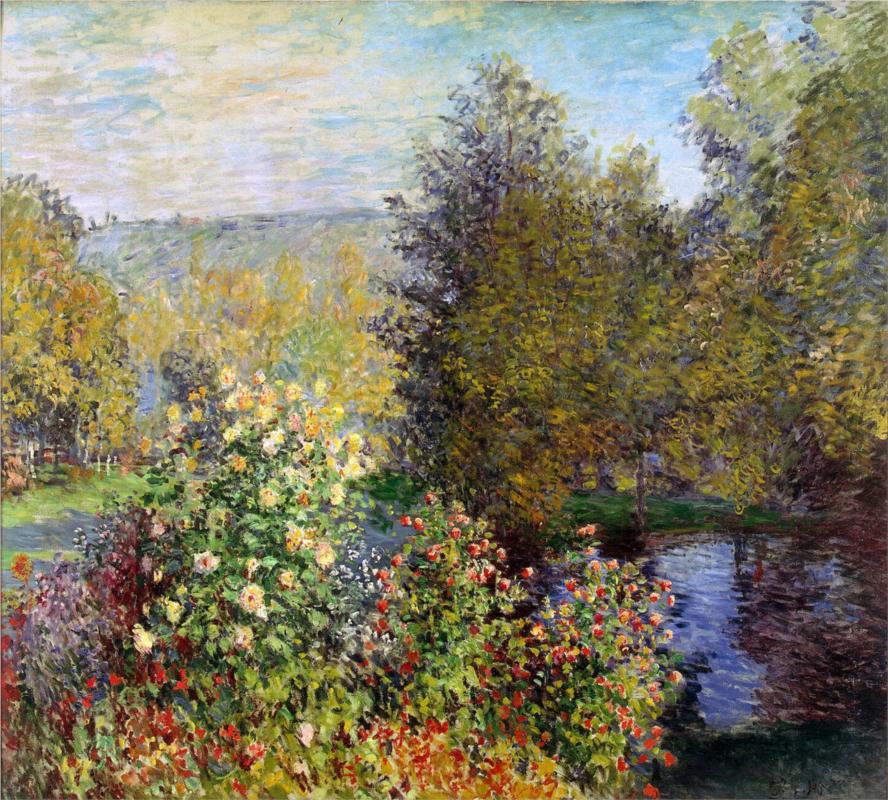

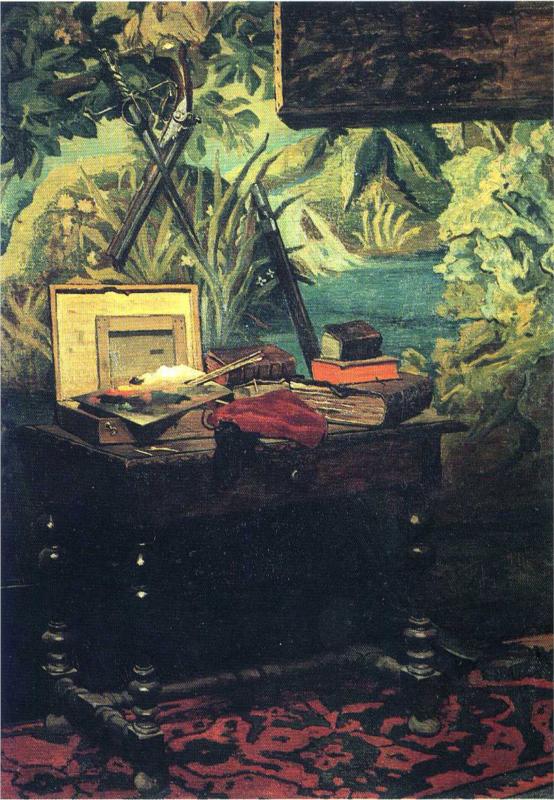

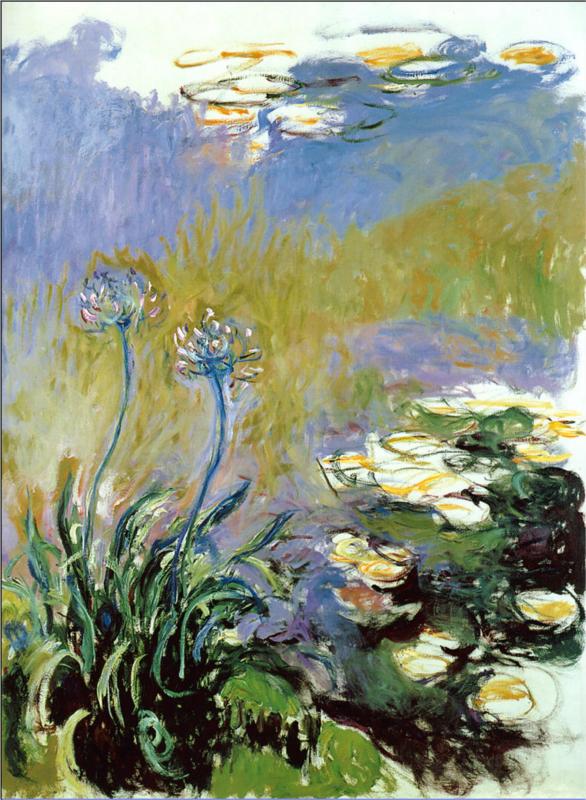

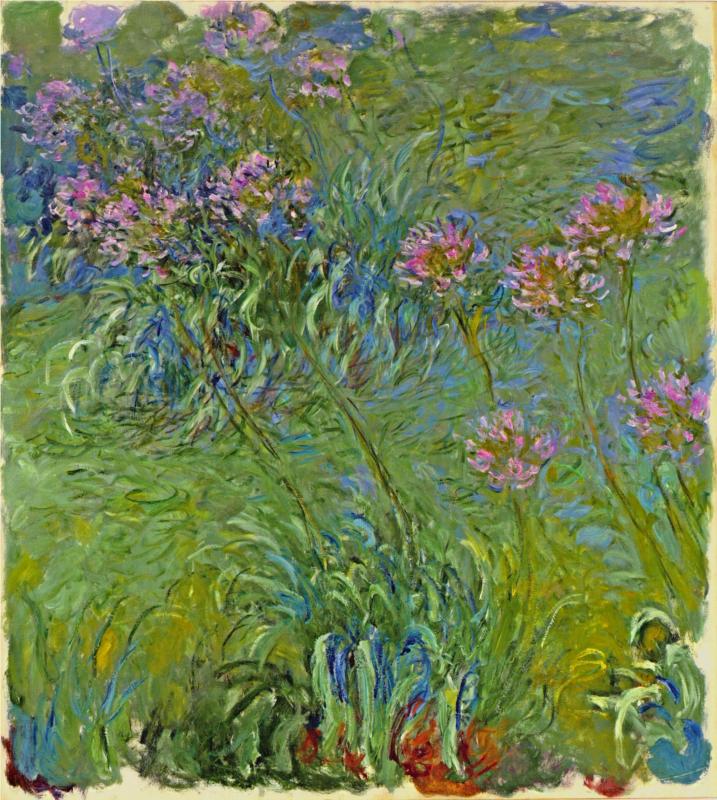

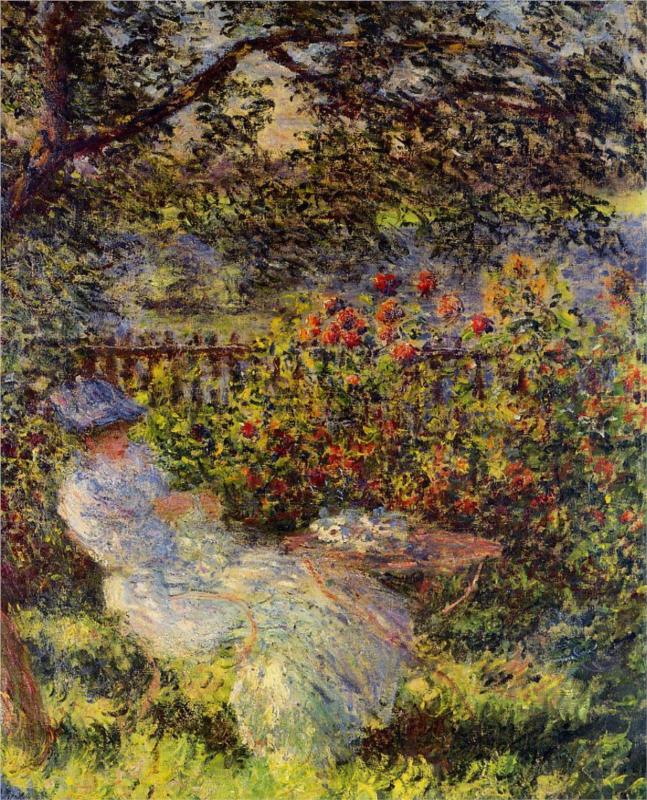

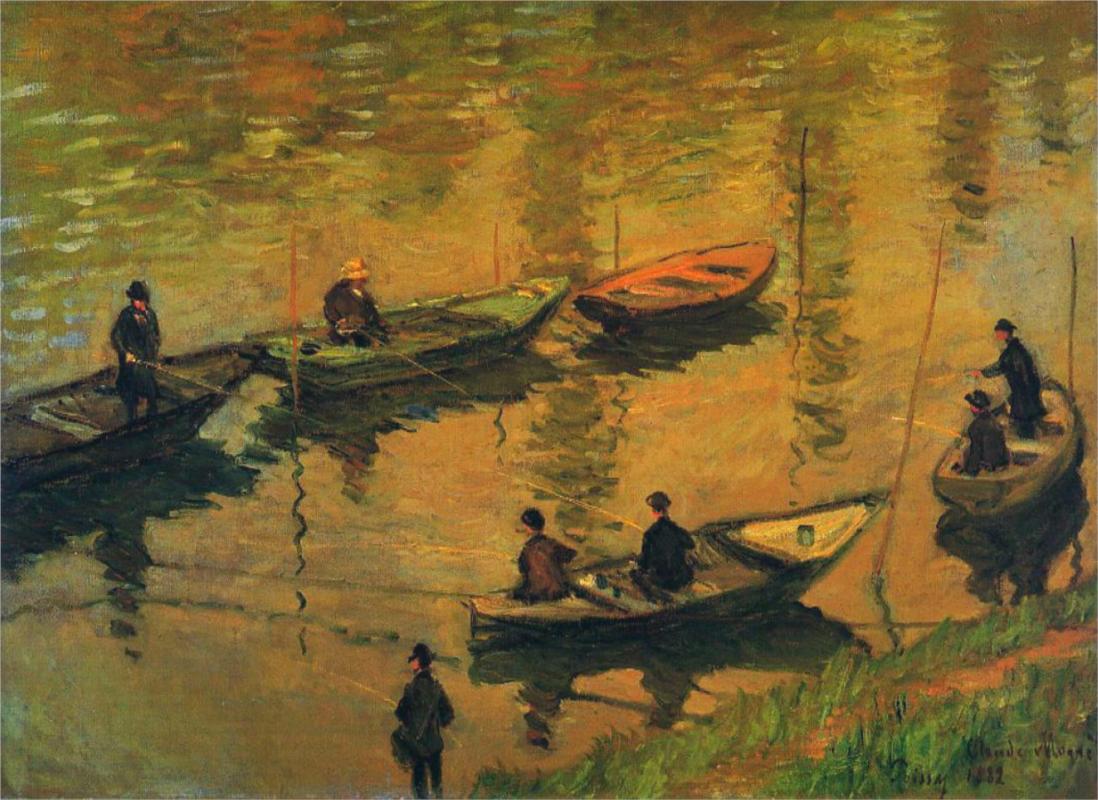

Illustration 1

Illustration 2

Illustration 3

Illustration 4

Illustration 5

Illustration 6

Illustration 7

Illustration 8

Illustration 9

Illustration 10

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE BLATCHFORD CONTROVERSIES TITLE

1. Christianity and Rationalism

2. Why I Believe in Christianity

3. Miracles and Modern Civilisation

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running