G. K. Chesterton

1915 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York, US.

This

work is published for the greater Glory of Jesus Christ through His

most

Holy Mother Mary and for the sanctification of the militant

Church and her members.

PUBLISHER

INDEX

THE APPETITE OF TYRANNY

THE FACTS OF THE CASE

Unless we are all mad, there is at the back of the most bewildering business a story: and if we are all mad, there is no such thing as madness. If I set a house on fire, it is quite true that I may illuminate many other people’s weaknesses as well as my own. It may be that the master of the house was burned because he was drunk; it may be that the mistress of the house was burned because she was stingy, and perished arguing about the expense of the fire-escape. It is, nevertheless, broadly true that they both were burned because I set fire to their house. That is the story of the thing. The mere facts of the story about the present European conflagration are quite as easy to tell.

Before we go on to the deeper things which make this war the most sincere war of human history, it is easy to answer the question of why England came to be in it at all, as one asks how a man fell down a coal-hole, or failed to keep an appointment. Facts are not the whole truth. But facts are facts, and in this case the facts are few and simple. Prussia, France, and England had all promised not to invade Belgium. Prussia proposed to invade Belgium, because it was the safest way of invading France. But Prussia promised that if she might break in, through her own broken promise and ours, she would break in and not steal. In other words, we were offered at the same instant a promise of faith in the future and a proposal of perjury in the present. Those interested in human origin may refer to an old Victorian writer of English, who, in the last and most restrained of his historical essays, wrote of Frederick the Great, the founder of this unchanging Prussian policy. After describing how Frederick broke the guarantee he had signed on behalf of Maria Theresa, he then describes how Frederick sought to put things straight by a promise that was an insult. “If she would but let him have Silesia, he would, he said, stand by her against any power which should try to deprive her of her other dominions, as if he was not already bound to stand by her, or as if his new promise could be of more value than the old one.” That passage was written by Macaulay, but so far as the mere contemporary facts are concerned, it might have been written by me.

Upon the immediate logical and legal origin of the English interest there can be no rational debate. There are some things so simple that one can almost prove them with plans and diagrams, as in Euclid. One could make a kind of comic calendar of what would have happened to the English diplomatist if he had been silenced every time by Prussian diplomacy. Suppose we arrange it in the form of a kind of diary.

July 24. Germany invades Belgium.

July 25. England declares war.

July 26. Germany promises not to annex Belgium.

July 27. England withdraws from the war.

July 28. Germany annexes Belgium. England declares war.

July 29. Germany promises not to annex France. England withdraws from the war.

July 30. Germany annexes France. England declares war.

July 31. Germany promises not to annex England.

Aug. 1. England withdraws from the war. Germany invades England . . .

How long is anybody expected to go with that sort of game, or keep peace at that illimitable price? How long must we pursue a road in which promises are all fetishes in front of us and all fragments behind us? No: upon the cold facts of the final negotiations, as told by any of the diplomatists in any of the documents, there is no doubt about the story. And no doubt about the villain of the story.

These are the last facts–the facts which involved England. It is equally easy to state the first facts–the facts which involved Europe. The Prince who practically ruled Austria was shot by certain persons whom the Austrian Government believed to be conspirators from Servia. The Austrian Government piled up arms and armies, but said not a word either to Servia their suspect or Italy their ally. From the documents it would seem that Austria kept everybody in the dark, except Prussia. It is probably nearer the truth to say that Prussia kept everybody in the dark, including Austria. But all that is what is called opinion, belief, conviction or common-sense, and we are not dealing with it here. The objective fact is that Austria told Servia to permit Servian officers to be suspended by the authority of Austrian officers, and told Servia to submit to this within forty-eight hours. In other words, the sovereign of Servia was practically told to take off not only the laurels of two great campaigns but his own lawful and national crown, and to do it in a time in which no respectable citizen is expected to discharge an hotel bill. Servia asked for time, for arbitration–in short, for peace. But Prussia had already begun to mobilise; and Prussia, presuming that Servia might thus be rescued, declared war.

Between these two ends of fact, the ultimatum to Servia, the ultimatum to Belgium, any one so inclined can of course talk as if everything were relative. If any one ask why the Czar should rush to the support of Servia, it is as easy to ask why the Kaiser should rush to the support of Austria. If any one say that the French would attack the Germans, it is sufficient to answer that the Germans did attack the French. There remain, however, two attitudes to consider, even perhaps two arguments to counter, which can best be considered and countered under this general head of facts. First of all, there is a curious, cloudy sort of argument, much affected by the professional rhetoricians of Prussia, who are sent out to instruct and correct the minds of Americans or Scandinavians. It consists of going into convulsions of incredulity and scorn at the mention of Russia’s responsibility for Servia or England’s responsibility for Belgium; and suggesting that, treaty or no treaty, frontier or no frontier, Russia would be out to slay Teutons or England to steal colonies. Here, as elsewhere, I think the professors dotted all over the Baltic plain fail in lucidity, and in the power of distinguishing ideas. Of course it is quite true that England has material interests to defend, and will probably use the opportunity to defend them: or, in other words, of course England, like everybody else, would be more comfortable if Prussia were less predominant. The fact remains that we did not do what the Germans did. We did not invade Holland to seize a naval and commercial advantage: and whether they say that we wished to do it in our greed, or feared to do it in our cowardice, the fact remains that we did not do it. Unless this common-sense principle be kept in view, I cannot conceive how any quarrel can possibly be judged. A contract may be made between two persons solely for material advantage on each side: but the moral advantage is still generally supposed to lie with the person who keeps the contract. Surely it cannot be dishonest to be honest–even if honesty is the best policy. Imagine the most complex maze of indirect motives; and still the man who keeps faith for money cannot possibly be worse than the man who breaks faith for money. It will be noted that this ultimate test applies in the same way to Servia as to Belgium and Britain. The Servians may not be a very peaceful people; but, on the occasion under discussion, it was certainly they who wanted peace. You may choose to think the Serb a sort of born robber: but on this occasion it was certainly the Austrian who was trying to rob. Similarly, you may call England perfidious as a sort of historical summary; and declare your private belief that Mr. Asquith was vowed from infancy to the ruin of the German Empire, a Hannibal and hater of the eagles. But, when all is said, it is nonsense to call a man perfidious because he keeps his promise. It is absurd to complain of the sudden treachery of a business man in turning up punctually to his appointment: or the unfair shock given to a creditor by the debtor paying his debts.

Lastly, there is an attitude not unknown in the crisis against which I should particularly like to protest. I should address my protest especially to those lovers and pursuers of Peace who, very short-sightedly, have occasionally adopted it. I mean the attitude which is impatient of these preliminary details about who did this or that, and whether it was right or wrong. They are satisfied with saying that an enormous calamity, called War, has been begun by some or all of us; and should be ended by some or all of us. To these people this preliminary chapter about the precise happenings must appear not only dry (and it must of necessity be the driest part of the task) but essentially needless and barren. I wish to tell these people that they are wrong; that they are wrong upon all principles of human justice and historic continuity: but that they are specially and supremely wrong upon their own principles of arbitration and international peace.

These sincere and high-minded peace-lovers are always telling us that citizens no longer settle their quarrels by private violence; and that nations should no longer settle theirs by public violence. They are always telling us that we no longer fight duels; and need no longer wage wars. In short, they perpetually base their peace proposals on the fact that an ordinary citizen no longer avenges himself with an axe. But how is he prevented from revenging himself with an axe? If he hits his neighbour on the head with the kitchen chopper, what do we do? Do we all join hands, like children playing Mulberry Bush, and say “We are all responsible for this; but let us hope it will not spread. Let us hope for the happy day when he shall leave off chopping at the man’s head; and when nobody shall ever chop anything for ever and ever.” Do we say “Let byegones be byegones; why go back to all the dull details with which the business began; who can tell with what sinister motives the man was standing there within reach of the hatchet?” We do not. We keep the peace in private life by asking for the facts of provocation, and the proper object of punishment. We do go into the dull details; we do enquire into the origins; we do emphatically enquire who it was that hit first. In short we do what I have done very briefly in this place.

Given this, it is indeed true that behind these facts there are truths; truths of a terrible, of a spiritual sort. In mere fact, the Germanic power has been wrong about Servia, wrong about Russia, wrong about Belgium, wrong about England, wrong about Italy. But there was a reason for its being wrong everywhere; and of that root reason, which has moved half the world against it, I shall speak later. For that is something too omnipresent to be proved, too indisputable to be helped by detail. It is nothing less than the locating, after more than a hundred years of recriminations and wrong explanations, of the modern European evil: the finding of the fountain from which poison has flowed upon all the nations of the earth.

I THE WAR ON THE WORD

It will hardly be denied that there is one lingering doubt in many, who recognise unavoidable self-defence in the instant parry of the English sword, and who have no great love for the sweeping sabre of Sadowa and Sedan. That doubt is the doubt whether Russia, as compared with Prussia, is sufficiently decent and democratic to be the ally of liberal and civilised powers. I take first, therefore, this matter of civilisation.

It is vital in a discussion like this, that we should make sure we are going by meanings and not by mere words. It is not necessary in any argument to settle what a word means or ought to mean. But it is necessary in every argument to settle what we propose to mean by the word. So long as our opponent understands what is the thing of which we are talking, it does not matter to the argument whether the word is or is not the one he would have chosen. A soldier does not say “We were ordered to go to Mechlin; but I would rather go to Malines.” He may discuss the etymology and archæology of the difference on the march; but the point is that he knows where to go. So long as we know what a given word is to mean in a given discussion, it does not even matter if it means something else in some other and quite distinct discussion. We have a perfect right to say that the width of a window comes to four feet; even if we instantly and cheerfully change the subject to the larger mammals; and say that an elephant has four feet. The identity of the words does not matter, because there is no doubt at all about the meanings; because nobody is likely to think of an elephant as four foot long, or of a window as having tusks and a curly trunk.

It is essential to emphasise this consciousness of the thing under discussion in connection with two or three words that are, as it were, the key-words of this war. One of them is the word “barbarian.” The Prussians apply it to the Russians: the Russians apply it to the Prussians. Both, I think, really mean something that really exists, name or no name. Both mean different things. And if we ask what these different things are, we shall understand why England and France prefer Russia; and consider Prussia the really dangerous barbarian of the two. To begin with, it goes so much deeper even than atrocities; of which, in the past at least, all the three Empires of Central Europe have partaken pretty equally, as they partook of Poland. An English writer, seeking to avert the war by warnings against Russian influence, said that the flogged backs of Polish women stood between us and the Alliance. But not long before, the flogging of women by an Austrian general led to that officer being thrashed in the streets of London by Barclay and Perkins’ draymen. And as for the third power, the Prussians, it seems clear that they have treated Belgian women in a style compared with which flogging might be called an official formality. But, as I say, something much deeper than any such recrimination lies behind the use of the word on either side. When the German Emperor complains of our allying ourselves with a barbaric and half-oriental power he is not (I assure you) shedding tears over the grave of Kosciusko. And when I say (as I do most heartily) that the German Emperor is a barbarian, I am not merely expressing any prejudices I may have against the profanation of churches or of children. My countrymen and I mean a certain and intelligible thing when we call the Prussians barbarians. It is quite different from the thing attributed to Russians; and it could not possibly be attributed to Russians. It is very important that the neutral world should understand what this thing is.

If the German calls the Russian barbarous he presumably means imperfectly civilised. There is a certain path along which Western nations have proceeded in recent times; and it is tenable that Russia has not proceeded so far as the others: that she has less of the special modern system in science, commerce, machinery, travel or political constitution. The Russ ploughs with an old plough; he wears a wild beard; he adores relics; his life is as rude and hard as that of a subject of Alfred the Great. Therefore he is, in the German sense, a barbarian. Poor fellows like Gorky and Dostoieffsky have to form their own reflections on the scenery, without the assistance of large quotations from Schiller on garden seats; or inscriptions directing them to pause and thank the All-Father for the finest view in Hesse-Pumpernickel. The Russians, having nothing but their faith, their fields, their great courage, and their self-governing communes, are quite cut off from what is called (in the fashionable street in Frankfort) The True, The Beautiful and The Good. There is a real sense in which one can call such backwardness barbaric; by comparison with the Kaiserstrasse; and in that sense it is true of Russia.

Now we, the French and English, do not mean this when we call the Prussians barbarians. If their cities soared higher than their flying ships, if their trains travelled faster than their bullets, we should still call them barbarians. We should know exactly what we meant by it; and we should know that it is true. For we do not mean anything that is an imperfect civilisation by accident. We mean something that is the enemy of civilisation by design. We mean something that is wilfully at war with the principles by which human society has been made possible hitherto. Of course it must be partly civilised even to destroy civilisation. Such ruin could not be wrought by the savages that are merely undeveloped or inert. You could not have even Huns without horses; or horses without horsemanship. You could not have even Danish pirates without ships, or ships without seamanship. This person, whom I may call the Positive Barbarian, must be rather more superficially up-to-date than what I may call the Negative Barbarian. Alaric was an officer in the Roman legions: but for all that he destroyed Rome. Nobody supposes that Eskimos could have done it at all neatly. But (in our meaning) barbarism is not a matter of methods but of aims. We say that these veneered vandals have the perfectly serious aim of destroying certain ideas which, as they think, the world has outgrown; without which, as we think, the world will die.

It is essential that this perilous peculiarity in the Pruss, or Positive Barbarian, should be seized. He has what he fancies is a new idea; and he is going to apply it to everybody. As a fact it is simply a false generalisation; but he is really trying to make it general. This does not apply to the Negative Barbarian: it does not apply to the Russian or the Servian, even if they are barbarians. If a Russian peasant does beat his wife, he does it because his fathers did it before him: he is likely to beat less rather than more as the past fades away. He does not think, as the Prussian would, that he has made a new discovery in physiology in finding that a woman is weaker than a man. If a Servian does knife his rival without a word, he does it because other Servians have done it. He may regard it even as piety, but certainly not as progress. He does not think, as the Prussian does, that he founds a new school of horology by starting before the word “Go.” He does not think he is in advance of the world in militarism, merely because he is behind it in morals. No; the danger of the Pruss is that he is prepared to fight for old errors as if they were new truths. He has somehow heard of certain shallow simplifications; and imagines that we have never heard of them. And, as I have said, his limited but very sincere lunacy concentrates chiefly in a desire to destroy two ideas, the twin root ideas of rational society. The first is the idea of record and promise: the second is the idea of reciprocity.

It is plain that the promise, or extension of responsibility through time, is what chiefly distinguishes us, I will not say from savages, but from brutes and reptiles. This was noted by the shrewdness of the Old Testament, when it summed up the dark irresponsible enormity of Leviathan in the words “Will he make a pact with thee?” The promise, like the wheel, is unknown in Nature: and is the first mark of man. Referring only to human civilisation it may be said with seriousness, that in the beginning was the Word. The vow is to the man what the song is to the bird, or the bark to the dog; his voice, whereby he is known. Just as a man who cannot keep an appointment is not fit even to fight a duel, so the man who cannot keep an appointment with himself is not sane enough even for suicide. It is not easy to mention anything on which the enormous apparatus of human life can be said to depend. But if it depends on anything, it is on this frail cord, flung from the forgotten hills of yesterday to the invisible mountains of to-morrow. On that solitary string hangs everything from Armageddon to an almanac, from a successful revolution to a return ticket. On that solitary string the Barbarian is hacking heavily, with a sabre which is fortunately blunt.

Any one can see this well enough, merely by reading the last negotiations between London and Berlin. The Prussians had made a new discovery in international politics: that it may often be convenient to make a promise; and yet curiously inconvenient to keep it. They were charmed, in their simple way, with this scientific discovery, and desired to communicate it to the world. They therefore promised England a promise, on condition that she broke a promise, and on the implied condition that the new promise might be broken as easily as the old one. To the profound astonishment of Prussia, this reasonable offer was refused! I believe that the astonishment of Prussia was quite sincere. That is what I mean when I say that the Barbarian is trying to cut away that cord of honesty and clear record, on which hangs all that men have made.

The friends of the German cause have complained that Asiatics and Africans upon the very verge of savagery have been brought against them from India and Algiers. And, in ordinary circumstances, I should sympathise with such a complaint made by a European people. But the circumstances are not ordinary. Here, again, the quite unique barbarism of Prussia goes deeper than what we call barbarities. About mere barbarities, it is true, the Turco and the Sikh would have a very good reply to the superior Teuton. The general and just reason for not using non-European tribes against Europeans is that given by Chatham against the use of the Red Indian: that such allies might do very diabolical things. But the poor Turco might not unreasonably ask, after a weekend in Belgium, what more diabolical things he could do than the highly cultured Germans were doing themselves. Nevertheless, as I say, the justification of any extra-European aid goes deeper than any such details. It rests upon the fact that even other civilisations, even much lower civilisations, even remote and repulsive civilisations, depend as much as our own on this primary principle on which the super-morality of Potsdam declares open War. Even savages promise things; and respect those who keep their promises. Even Orientals write things down: and though they write them from right to left, they know the importance of a scrap of paper. Many merchants will tell you that the word of the sinister and almost unhuman Chinaman is often as good as his bond: and it was amid palm trees and Syrian pavilions that the great utterance opened the tabernacle, to him that sweareth to his hurt and changeth not. There is doubtless a dense labyrinth of duplicity in the East, and perhaps more guile in the individual Asiatic than in the individual German. But we are not talking of the violations of human morality in various parts of the world. We are talking about a new and inhuman morality, which denies altogether the day of obligation. The Prussians have been told by their literary men that everything depends upon Mood: and by their politicians that all arrangements dissolve before “necessity.” That is the importance of the German Chancellor’s phrase. He did not allege some special excuse in the case of Belgium, which might make it seem an exception that proved the rule. He distinctly argued, as on a principle applicable to other cases, that victory was a necessity and honour was a scrap of paper. And it is evident that the half-educated Prussian imagination really cannot get any further than this. It cannot see that if everybody’s action were entirely incalculable from hour to hour, it would not only be the end of all promises, but the end of all projects. In not being able to see that, the Berlin philosopher is really on a lower mental level than the Arab who respects the salt, or the Brahmin who preserves the caste. And in this quarrel we have a right to come with scimitars as well as sabres, with bows as well as rifles, with assegai and tomahawk and boomerang, because there is in all these at least a seed of civilisation that these intellectual anarchists would kill. And if they should find us in our last stand girt with such strange swords and following unfamiliar ensigns, and ask us for what we fight in so singular a company, we shall know what to reply: “We fight for the trust and for the tryst; for fixed memories and the possible meeting of men; for all that makes life anything but an uncontrollable nightmare. We fight for the long arm of honour and remembrance; for all that can lift a man above the quicksands of his moods, and give him the mastery of time.”

II THE REFUSAL OF RECIPROCITY

In the last summary I suggested that Barbarism, as we mean it, is not mere ignorance or even mere cruelty. It has a more precise sense, and means militant hostility to certain necessary human ideas. I took the case of the vow or the contract, which Prussian intellectualism would destroy. I urged that the Prussian is a spiritual Barbarian, because he is not bound by his own past, any more than a man in a dream. He avows that when he promised to respect a frontier on Monday, he did not foresee what he calls “the necessity” of not respecting it on Tuesday. In short, he is like a child, who at the end of all reasonable explanations and reminders of admitted arrangements, has no answer except “But I want to.”

There is another idea in human arrangements so fundamental as to be forgotten; but now for the first time denied. It may be called the idea of reciprocity; or, in better English, of give and take. The Prussian appears to be quite intellectually incapable of this thought. He cannot, I think, conceive the idea that is the foundation of all comedy; that, in the eyes of the other man, he is only the other man. And if we carry this clue through the institutions of Prussianised Germany, we shall find how curiously his mind has been limited in the matter. The German differs from other patriots in the inability to understand patriotism. Other European peoples pity the Poles or the Welsh for their violated borders; but Germans pity only themselves. They might take forcible possession of the Severn or the Danube, of the Thames or the Tiber, of the Garry or the Garonne–and they would still be singing sadly about how fast and true stands the watch on Rhine; and what a shame it would be if any one took their own little river away from them. That is what I mean by not being reciprocal: and you will find it in all that they do: as in all that is done by savages.

Here, again, it is very necessary to avoid confusing this soul of the savage with mere savagery in the sense of brutality or butchery; in which the Greeks, the French and all the most civilised nations have indulged in hours of abnormal panic or revenge. Accusations of cruelty are generally mutual. But it is the point about the Prussian that with him nothing is mutual. The definition of the true savage does not concern itself even with how much more he hurts strangers or captives than do the other tribes of men. The definition of the true savage is that he laughs when he hurts you; and howls when you hurt him. This extraordinary inequality in the mind is in every act and word that comes from Berlin. For instance, no man of the world believes all he sees in the newspapers; and no journalist believes a quarter of it. We should, therefore, be quite ready in the ordinary way to take a great deal off the tales of German atrocities; to doubt this story or deny that. But there is one thing that we cannot doubt or deny: the seal and authority of the Emperor. In the Imperial proclamation the fact that certain “frightful” things have been done is admitted; and justified on the ground of their frightfulness. It was a military necessity to terrify the peaceful populations with something that was not civilised, something that was hardly human. Very well. That is an intelligible policy: and in that sense an intelligible argument. An army endangered by foreigners may do the most frightful things. But then we turn the next page of the Kaiser’s public diary, and we find him writing to the President of the United States, to complain that the English are using Dum-dum bullets and violating various regulations of the Hague Conference. I pass for the present the question of whether there is a word of truth in these charges. I am content to gaze rapturously at the blinking eyes of the True, or Positive, Barbarian. I suppose he would be quite puzzled if we said that violating the Hague Conference was “a military necessity” to us; or that the rules of the Conference were only a scrap of paper. He would be quite pained if we said that Dum-dum bullets, “by their very frightfulness,” would be very useful to keep conquered Germans in order. Do what he will, he cannot get outside the idea that he, because he is he and not you, is free to break the law; and also to appeal to the law. It is said that the Prussian officers play at a game called Kriegsspiel, or the War Game. But in truth they could not play at any game; for the essence of every game is that the rules are the same on both sides.

But taking every German institution in turn, the case is the same; and it is not a case of mere bloodshed or military bravado. The duel, for example, can legitimately be called a barbaric thing; but the word is here used in another sense. There are duels in Germany; but so there are in France, Italy, Belgium, and Spain; indeed, there are duels wherever there are dentists, newspapers, Turkish baths, time-tables, and all the curses of civilisation; except in England and a corner of America. You may happen to regard the duel as a historic relic of the more barbaric States on which these modern States were built. It might equally well be maintained that the duel is everywhere the sign of high civilisation; being the sign of its more delicate sense of honour, its more vulnerable vanity, or its greater dread of social disrepute. But whichever of the two views you take, you must concede that the essence of the duel is an armed equality. I should not, therefore, apply the word barbaric, as I am using it, to the duels of German officers, or even to the broadsword combats that are conventional among the German students. I do not see why a young Prussian should not have scars all over his face if he likes them; nay, they are often the redeeming points of interest on an otherwise somewhat unenlightening countenance. The duel may be defended; the sham duel may be defended.

What cannot be defended is something really peculiar to Prussia, of which we hear numberless stories, some of them certainly true. It might be called the one-sided duel. I mean the idea that there is some sort of dignity in drawing the sword upon a man who has not got a sword; a waiter, or a shop assistant, or even a schoolboy. One of the officers of the Kaiser in the affair at Saberne was found industriously hacking at a cripple. In all these matters I would avoid sentiment. We must not lose our tempers at the mere cruelty of the thing; but pursue the strict psychological distinction. Others besides German soldiers have slain the defenceless, for loot or lust or private malice, like any other murderer. The point is that nowhere else but in Prussian Germany is any theory of honour mixed up with such things; any more than with poisoning or picking pockets. No French, English, Italian or American gentleman would think he had in some way cleared his own character by sticking his sabre through some ridiculous greengrocer who had nothing in his hand but a cucumber. It would seem as if the word which is translated from the German as “honour” must really mean something quite different in German. It seems to mean something more like what we should call “prestige.”

The fundamental fact, however, is the absence of the reciprocal idea. The Prussian is not sufficiently civilised for the duel. Even when he crosses swords with us his thoughts are not as our thoughts; when we both glorify war, we are glorifying different things. Our medals are wrought like his, but they do not mean the same thing; our regiments are cheered as his are, but the thought in the heart is not the same; the Iron Cross is on the bosom of his king, but it is not the sign of our God. For we, alas, follow our God with many relapses and self-contradictions, but he follows his very consistently. Through all the things that we have examined, the view of national boundaries, the view of military methods, the view of personal honour and self-defence, there runs in their case something of an atrocious simplicity; something too simple for us to understand: the idea that glory consists in holding the steel, and not in facing it.

If further examples were necessary, it would be easy to give hundreds of them. Let us leave, for the moment, the relation between man and man in the thing called the duel. Let us take the relation between man and woman, in that immortal duel which we call a marriage. Here again we shall find that other Christian civilisations aim at some kind of equality; even if the balance be irrational or dangerous. Thus, the two extremes of the treatment of women might be represented by what are called the respectable classes in America and in France. In America they choose the risk of comradeship; in France the compensation of courtesy. In America it is practically possible for any young gentleman to take any young lady for what he calls (I deeply regret to say) a joy-ride; but at least the man goes with the woman as much as the woman with the man. In France the young woman is protected like a nun while she is unmarried; but when she is a mother she is really a holy woman; and when she is a grandmother she is a holy terror. By both extremes the woman gets something back out of life. There is only one place where she gets little or nothing back; and that is the north of Germany. France and America aim alike at equality; America by similarity; France by dissimilarity. But North Germany does definitely aim at inequality. The woman stands up, with no more irritation than a butler; the man sits down, with no more embarrassment than a guest. This is the cool affirmation of inferiority, as in the case of the sabre and the tradesman. “Thou goest with women; forget not thy whip,” said Nietzsche. It will be observed that he does not say “poker”; which might come more naturally to the mind of a more common or Christian wife-beater. But then a poker is a part of domesticity; and might be used by the wife as well as the husband. In fact, it often is. The sword and the whip are the weapons of a privileged caste.

Pass from the closest of all differences, that between husband and wife, to the most distant of all differences, that of the remote and unrelated races who have seldom seen each other’s faces, and never been tinged with each other’s blood. Here we still find the same unvarying Prussian principle. Any European might feel a genuine fear of the Yellow Peril; and many Englishmen, Frenchmen, and Russians have felt and expressed it. Many might say, and have said, that the Heathen Chinee is very heathen indeed; that if he ever advances against us he will trample and torture and utterly destroy, in a way that Eastern people do, but Western people do not. Nor do I doubt the German Emperor’s sincerity when he sought to point out to us how abnormal and abominable such a nightmare campaign would be, supposing that it could ever come. But now comes the comic irony; which never fails to follow on the attempt of the Prussian to be philosophic. For the Kaiser, after explaining to his troops how important it was to avoid Eastern Barbarism, instantly commanded them to become Eastern Barbarians. He told them, in so many words, to be Huns: and leave nothing living or standing behind them. In fact, he frankly offered a new army corps of aboriginal Tartars to the Far East, within such time as it may take a bewildered Hanoverian to turn into a Tartar. Any one who has the painful habit of personal thought, will perceive here at once the non-reciprocal principle again. Boiled down to its bones of logic, it means simply this: “I am a German and you are a Chinaman. Therefore I, being a German, have a right to be a Chinaman. But you have no right to be a Chinaman; because you are only a Chinaman.” This is probably the highest point to which the German culture has risen.

The principle here neglected, which may be called Mutuality by those who misunderstand and dislike the word Equality, does not offer so clear a distinction between the Prussian and the other peoples as did the first Prussian principle of an infinite and destructive opportunism; or, in other words, the principle of being unprincipled. Nor upon this second can one take up so obvious a position touching the other civilisations or semi-civilisations of the world. Some idea of oath and bond there is in the rudest tribes, in the darkest continents. But it might be maintained, of the more delicate and imaginative element of reciprocity, that a cannibal in Borneo understands it almost as little as a professor in Berlin. A narrow and one-sided seriousness is the fault of barbarians all over the world. This may have been the meaning, for aught I know, of the one eye of the Cyclops: that the Barbarian cannot see round things or look at them from two points of view; and thus becomes a blind beast and an eater of men. Certainly there can be no better summary of the savage than this, which as we have seen, unfits him for the duel. He is the man who cannot love–no, nor even hate–his neighbour as himself.

But this quality in Prussia does have one effect which has reference to the same question of the lower civilisations. It disposes once and for all at least of the civilising mission of Germany. Evidently the Germans are the last people in the world to be trusted with the task. They are as shortsighted morally as physically. What is their sophism of “necessity” but an inability to imagine to-morrow morning? What is their non-reciprocity but an inability to imagine, not a god or devil, but merely another man? Are these to judge mankind? Men of two tribes in Africa not only know that they are all men, but can understand that they are all black men. In this they are quite seriously in advance of the intellectual Prussian; who cannot be got to see that we are all white men. The ordinary eye is unable to perceive in the North-East Teuton anything that marks him out especially from the more colourless classes of the rest of Aryan mankind. He is simply a white man, with a tendency to the grey or the drab. Yet he will explain, in serious official documents, that the difference between him and us is a difference between “the master-race and the inferior-race.” The collapse of German philosophy always occurs at the beginning rather than the end of an argument; and the difficulty here is that there is no way of testing which is a master-race except by asking which is your own race. If you cannot find out (as is usually the case) you fall back on the absurd occupation of writing history about pre-historic times. But I suggest quite seriously that if the Germans can give their philosophy to the Hottentots, there is no reason why they should not give their sense of superiority to the Hottentots. If they can see such fine shades between the Goth and the Gaul, there is no reason why similar shades should not lift the savage above other savages; why any Ojibway should not discover that he is one tint redder than the Dacotahs; or any nigger in the Cameroons say he is not so black as he is painted. For this principle of a quite unproved racial supremacy is the last and worst of the refusals of reciprocity. The Prussian calls all men to admire the beauty of his large blue eyes. If they do, it is because they have inferior eyes: if they don’t, it is because they have no eyes.

Wherever the most miserable remnant of our race, astray and dried up in deserts, or buried forever under the fall of bad civilisations, has some feeble memory that men are men, that bargains are bargains, that there are two sides to a question, or even that it takes two to make a quarrel–that remnant has the right to resist the New Culture, to the knife and club and the splintered stone. For the Prussian begins all his culture by that act which is the destruction of all creative thought and constructive action. He breaks that mirror in the mind, in which a man can see the face of his friend or foe.

III THE APPETITE OF TYRANNY

The German Emperor has reproached this country with allying itself with “barbaric and semi-oriental power.” We have already considered in what sense we use the word barbaric: it is in the sense of one who is hostile to civilisation, not one who is insufficient in it. But when we pass from the idea of the barbaric to the idea of the oriental, the case is even more curious. There is nothing particularly Tartar in Russian affairs, except the fact that Russia expelled the Tartars. The Eastern invader occupied and crushed the country for many years; but that is equally true of Greece, of Spain and even of Austria. If Russia has suffered from the East she has suffered in order to resist it: and it is rather hard that the very miracle of her escape should make a mystery about her origin. Jonah may or may not have been three days inside a fish, but that does not make him a merman. And in all the other cases of European nations who escaped the monstrous captivity, we do admit the purity and continuity of the European type. We consider the old Eastern rule as a wound, but not as a stain. Copper-coloured men out of Africa overruled for centuries the religion and patriotism of Spaniards. Yet I have never heard that Don Quixote was an African fable on the lines of Uncle Remus. I have never heard that the heavy black in the pictures of Velasquez was due to a negro ancestry. In the case of Spain, which is close to us, we can recognise the resurrection of a Christian and cultured nation after its age of bondage. But Russia is rather remote; and those to whom nations are but names in newspapers can really fancy, like Mr. Baring’s friend, that all Russian churches are “mosques.” Yet the land of Turgenev is not a wilderness of fakirs; and even the fanatical Russian is as proud of being different from the Mongol, as the fanatical Spaniard was proud of being different from the Moor.

The town of Reading, as it exists, offers few opportunities for piracy on the high seas: yet it was the camp of the pirates in Alfred’s day. I should think it hard to call the people of Berkshire half-Danish, merely because they drove out the Danes. In short, some temporary submergence under the savage flood was the fate of many of the most civilised states of Christendom; and it is quite ridiculous to argue that Russia, which wrestled hardest, must have recovered least. Everywhere, doubtless, the East spread a sort of enamel over the conquered countries, but everywhere the enamel cracked. Actual history, in fact, is exactly opposite to the cheap proverb invented against the Muscovite. It is not true to say “Scratch a Russian and you find a Tartar.” In the darkest hour of the barbaric dominion it was truer to say, “Scratch a Tartar and you find a Russian.” It was the civilisation that survived under all the barbarism. This vital romance of Russia, this revolution against Asia, can be proved in pure fact: not only from the almost superhuman activity of Russia during the struggle, but also (which is much rarer as human history goes) by her quite consistent conduct since. She is the only great nation which has really expelled the Mongol from her country, and continued to protest against the presence of the Mongol in her continent. Knowing what he had been in Russia, she knew what he would be in Europe. In this she pursued a logical line of thought which was, if anything, too unsympathetic with the energies and religions of the East. Every other country, one may say, has been an ally of the Turk; that is, of the Mongol and the Moslem. The French played them as pieces against Austria; the English warmly supported them under the Palmerston régime; even the young Italians sent troops to the Crimea; and of Prussia and her Austrian vassal it is nowadays needless to speak. For good or evil, it is the fact of history that Russia is the only Power in Europe that has never supported the Crescent against the Cross.

That, doubtless, will appear an unimportant matter; but it may become important under certain peculiar conditions. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that there were a powerful prince in Europe who had gone ostentatiously out of his way to pay reverence to the remains of the Tartar, Mongol and Moslem, left as an outpost in Europe. Suppose there were a Christian Emperor who could not even go to the tomb of the Crucified, without pausing to congratulate the last and living crucifier. If there were an Emperor who gave guns and guides and maps and drill instructors to defend the remains of the Mongol in Christendom, what should we say to him? I think at least we might ask him what he meant by his impudence, when he talked about supporting a semi-oriental power. That we support a semi-oriental power, we deny. That he has supported an entirely oriental power cannot be denied–no, not even by the man who did it.

But here is to be noted the essential difference between Russia and Prussia; especially by those who use the ordinary Liberal arguments against the latter. Russia has a policy which she pursues, if you will, through evil and good; but at least so as to produce good as well as evil. Let it be granted that the policy has made her oppressive to the Finns and the Poles–though the Russian Poles feel far less oppressed than do the Prussian Poles. But it is a mere historic fact, that if Russia has been a despot to some small nations, she has been a deliverer to others. She did, so far as in her lay, emancipate the Servians or the Montenegrins. But whom did Prussia ever emancipate–even by accident? It is indeed somewhat extraordinary that in the perpetual permutations of international politics the Hohenzollerns have never gone astray into the path of enlightenment. They have been in alliance with almost everybody off and on; with France, with England, with Austria, with Russia. Can any one candidly say that they have left on any one of these people the faintest impress of progress or liberation? Prussia was the enemy of the French Monarchy; but a worse enemy of the French Revolution. Prussia had been an enemy of the Czar; but she was a worse enemy of the Duma. Prussia totally disregarded Austrian rights; but she is to-day quite ready to inflict Austrian wrongs. This is the strong particular difference between the one empire and the other. Russia is pursuing certain intelligible and sincere ends, which to her at least are ideals, and for which, therefore, she will make sacrifices and will protect the weak. But the North German soldier is a sort of abstract tyrant, everywhere and always on the side of materialistic tyranny. This Teuton in uniform has been found in strange places; shooting farmers before Saratoga and flogging soldiers in Surrey, hanging niggers in Africa and raping girls in Wicklow; but never, by some mysterious fatality, lending a hand to the freeing of a single city or the independence of one solitary flag. Wherever scorn and prosperous oppression are, there is the Prussian; unconsciously consistent, instinctively restrictive, innocently evil; “following darkness like a dream.”

Suppose we heard of a person (gifted with some longevity) who had helped Alva to persecute Dutch Protestants, then helped Cromwell to persecute Irish Catholics, and then helped Claverhouse to persecute Scotch Puritans, we should find it rather easier to call him a persecutor than to call him a Protestant or a Catholic. Curiously enough this is actually the position in which the Prussian stands in Europe. No argument can alter the fact that in three converging and conclusive cases he has been on the side of three distinct rulers of different religions, who had nothing whatever in common except that they were ruling oppressively. In these three Governments, taken separately, one can see something excusable or at least human. When the Kaiser encouraged the Russian rulers to crush the Revolution, the Russian rulers undoubtedly believed they were wrestling with an inferno of atheism and anarchy. A Socialist of the ordinary English kind cried out upon me when I spoke of Stolypin, and said he was chiefly known by the halter called “Stolypin’s Necktie.” As a fact, there were many other things interesting about Stolypin besides his necktie: his policy of peasant proprietorship, his extraordinary personal courage, and certainly none more interesting than that movement in his death agony, when he made the sign of the cross towards the Czar, as the crown and captain of his Christianity. But the Kaiser does not regard the Czar as the captain of Christianity. Far from it. What he supported in Stolypin was the necktie and nothing but the necktie: the gallows and not the cross. The Russian ruler did believe that the Orthodox Church was orthodox. The Austrian Archduke did really desire to make the Catholic Church catholic. He did really believe that he was being Pro-Catholic in being Pro-Austrian. But the Kaiser cannot be Pro-Catholic, and therefore cannot have been really Pro-Austrian, he was simply and solely Anti-Servian. Nay, even in the cruel and sterile strength of Turkey, any one with imagination can see something of the tragedy and therefore of the tenderness of true belief. The worst that can be said of the Moslems is, as the poet put it, they offered to man the choice of the Koran or the sword. The best that can be said for the German is that he does not care about the Koran, but is satisfied if he can have the sword. And for me, I confess, even the sins of these three other striving empires take on, in comparison, something that is sorrowful and dignified: and I feel they do not deserve that this little Lutheran lounger should patronise all that is evil in them, while ignoring all that is good. He is not Catholic, he is not Orthodox, he is not Mahomedan. He is merely an old gentleman who wishes to share the crime though he cannot share the creed. He desires to be a persecutor by the pang without the palm. So strongly do all the instincts of the Prussian drive against liberty, that he would rather oppress other people’s subjects than think of anybody going without the benefits of oppression. He is a sort of disinterested despot. He is as disinterested as the devil who is ready to do any one’s dirty work.

This would seem obviously fantastic were it not supported by solid facts which cannot be explained otherwise. Indeed it would be inconceivable if we were thinking of a whole people, consisting of free and varied individuals. But in Prussia the governing class is really a governing class: and a very few people are needed to think along these lines to make all the other people act along them. And the paradox of Prussia is this: that while its princes and nobles have no other aim on this earth but to destroy democracy wherever it shows itself, they have contrived to get themselves trusted, not as wardens of the past but as forerunners of the future. Even they cannot believe that their theory is popular, but they do believe that it is progressive. Here again we find the spiritual chasm between the two monarchies in question. The Russian institutions are, in many cases, really left in the rear of the Russian people, and many of the Russian people know it. But the Prussian institutions are supposed to be in advance of the Prussian people, and most of the Prussian people believe it. It is thus much easier for the warlords to go everywhere and impose a hopeless slavery upon every one, for they have already imposed a sort of hopeful slavery on their own simple race.

And when men shall speak to us of the hoary iniquities of Russia and of how antiquated is the Russian system, we shall answer “Yes; that is the superiority of Russia.” Their institutions are part of their history, whether as relics or fossils. Their abuses have really been uses: that is to say, they have been used up. If they have old engines of terror or torment, they may fall to pieces from mere rust, like an old coat of armour. But in the case of the Prussian tyranny, if it be tyranny at all, it is the whole point of its claim that it is not antiquated, but just going to begin, like the showman. Prussia has a whole thriving factory of thumbscrews, a whole humming workshop of wheels and racks, of the newest and neatest pattern, with which to win back Europe to the Reaction . . . infandum renovare dolorem. And if we wish to test the truth of this, it can be done by the same method which showed us that Russia, if her race or religion could sometimes make her an invader and an oppressor, could also be made an emancipator and a knight errant. In the same way, if the Russian institutions are old-fashioned, they honestly exhibit the good as well as the bad that can be found in old-fashioned things. In their police system they have an inequality which is against our ideas of law. But in their commune system they have an equality that is older than law itself. Even when they flogged each other like barbarians, they called upon each other by their Christian names like children. At their worst they retained all the best of a rude society. At their best, they are simply good, like good children or good nuns. But in Prussia all that is best in the civilised machinery is put at the service of all that is worst in the barbaric mind. Here again the Prussian has no accidental merits, none of those lucky survivals, none of those late repentances, which make the patchwork glory of Russia. Here all is sharpened to a point and pointed to a purpose and that purpose, if words and acts have any meaning at all, is the destruction of liberty throughout the world.

IV THE ESCAPE OF FOLLY

In considering the Prussian point of view we have been considering what seems to be mainly a mental limitation: a kind of knot in the brain. Towards the problem of Slav population, of English colonisation, of French armies and reinforcements, it shows the same strange philosophic sulks. So far as I can follow it, it seems to amount to saying “It is very wrong that you should be superior to me, because I am superior to you.” The spokesmen of this system seem to have a curious capacity for concentrating this entanglement or contradiction, sometimes into a single paragraph, or even a single sentence. I have already referred to the German Emperor’s celebrated suggestion that in order to avert the peril of Hunnishness we should all become Huns. A much stronger instance is his more recent order to his troops touching the war in Northern France. As most people know, his words ran “It is my Royal and Imperial command that you concentrate your energies, for the immediate present, upon one single purpose, and that is that you address all your skill and all the valour of my soldiers to exterminate first the treacherous English and to walk over General French’s contemptible little Army.” The rudeness of the remark an Englishman can afford to pass over; what I am interested in is the mentality; the train of thought that can manage to entangle itself even in so brief a space. If French’s little Army is contemptible, it would seem clear that all the skill and valour of the German Army had better not be concentrated on it, but on the larger and less contemptible allies. If all the skill and valour of the German Army are concentrated on it, it is not being treated as contemptible. But the Prussian rhetorician had two incompatible sentiments in his mind; and he insisted on saying them both at once. He wanted to think of an English Army as a small thing; but he also wanted to think of an English defeat as a big thing. He wanted to exult, at the same moment, in the utter weakness of the British in their attack; and the supreme skill and valour of the Germans in repelling such an attack. Somehow it must be made a common and obvious collapse for England; and yet a daring and unexpected triumph for Germany. In trying to express these contradictory conceptions simultaneously, he got rather mixed. Therefore he bade Germania fill all her vales and mountains with the dying agonies of this almost invisible earwig; and let the impure blood of this cockroach redden the Rhine down to the sea.

But it would be unfair to base the criticism on the utterance of any accidental and hereditary prince: and it is quite equally clear in the case of the philosophers who have been held up to us, even in England, as the very prophets of progress. And in nothing is it shown more sharply than in the curious confused talk about Race and especially about the Teutonic Race. Professor Harnack and similar people are reproaching us, I understand, for having broken “the bond of Teutonism”: a bond which the Prussians have strictly observed both in breach and observance. We note it in their open annexation of lands wholly inhabited by negroes, such as Denmark. We note it equally in their instant and joyful recognition of the flaxen hair and light blue eyes of the Turks. But it is still the abstract principle of Professor Harnack which interests me most; and in following it I have the same complexity of enquiry, but the same simplicity of result. Comparing the Professor’s concern about “Teutonism” with his unconcern about Belgium, I can only reach the following result: “A man need not keep a promise he has made. But a man must keep a promise he has not made.” There certainly was a treaty binding Britain to Belgium; if it was only a scrap of paper. If there was any treaty binding Britain to Teutonism it is, to say the least of it, a lost scrap of paper: almost what one might call a scrap of waste-paper. Here again the pendants under consideration exhibit the illogical perversity that makes the brain reel. There is obligation and there is no obligation: sometimes it appears that Germany and England must keep faith with each other; sometimes that Germany need not keep faith with anybody and anything; sometimes that we alone among European peoples are almost entitled to be Germans; sometimes that beside us Russians and Frenchmen almost rise to a Germanic loveliness of character. But through all there is, hazy but not hypocritical, this sense of some common Teutonism.

Professor Haeckel, another of the witnesses raised up against us, attained to some celebrity at one time through proving the remarkable resemblance between two different things by printing duplicate pictures of the same thing. Professor Haeckel’s contribution to biology, in this case, was exactly like Professor Harnack’s contribution to ethnology. Professor Harnack knows what a German is like. When he wants to imagine what an Englishman is like, he simply photographs the same German over again. In both cases there is probably sincerity as well as simplicity. Haeckel was so certain that the species illustrated in embryo really are closely related and linked up, that it seemed to him a small thing to simplify it by mere repetition. Harnack is so certain that the German and Englishman are almost alike, that he really risks the generalisation that they are exactly alike. He photographs, so to speak, the same fair and foolish face twice over; and calls it a remarkable resemblance between cousins. Thus he can prove the existence of Teutonism just about as conclusively as Haeckel has proved the more tenable proposition of the non-existence of God. Now the German and the Englishman are not in the least alike–except in the sense that neither of them are negroes. They are, in everything good and evil, more unlike than any other two men we can take at random from the great European family. They are opposite from the roots of their history, nay, of their geography. It is an understatement to call Britain insular. Britain is not only an island, but an island slashed by the sea till it nearly splits into three islands; and even the Midlands can almost smell the salt. Germany is a powerful, beautiful and fertile inland country, which can only find the sea by one or two twisted and narrow paths, as people find a subterranean lake. Thus the British Navy is really national because it is natural; it has co-hered out of hundreds of accidental adventures of ships and shipmen before Chaucer’s time and after it. But the German Navy is an artificial thing; as artificial as a constructed Alp would be in England. William II has simply copied the British Navy as Frederick II copied the French Army: and this Japanese or anti-like assiduity in imitation is one of the hundred qualities which the Germans have and the English markedly have not. There are other German superiorities which are very much superior. The one or two really jolly things that the Germans have got are precisely the things which the English haven’t got: notably a real habit of popular music and of the ancient songs of the people, not merely spreading from the towns or caught from the professionals. In this the Germans rather resemble the Welsh: though heaven knows what becomes of Teutonism if they do. But the difference between the Germans and the English goes deeper than all these signs of it; they differ more than any other two Europeans in the normal posture of the mind. Above all, they differ in what is the most English of all English traits; that shame which the French may be right in calling “the bad shame”; for it is certainly mixed up with pride and suspicion, the upshot of which we call shyness. Even an Englishman’s rudeness is often rooted in his being embarrassed. But a German’s rudeness is rooted in his never being embarrassed. He eats and makes love noisily. He never feels a speech or a song or a sermon or a large meal to be what the English call “out of place” in particular circumstances. When Germans are patriotic and religious they have no reactions against patriotism and religion as have the English and the French. Nay, the mistake of Germany in the modern disaster largely arose from the facts that she thought England was simple when England is very subtle. She thought that because our politics have become largely financial that they had become wholly financial; that because our aristocrats had become pretty cynical that they had become entirely corrupt. They could not seize the subtlety by which a rather used-up English gentleman might sell a coronet when he would not sell a fortress; might lower the public standards and yet refuse to lower the flag. In short, the Germans are quite sure that they understand us entirely, because they do not understand us at all. Possibly if they began to understand us they might hate us even more: but I would rather be hated for some small but real reason than pursued with love on account of all kinds of qualities which I do not possess and which I do not desire. And when the Germans get their first genuine glimpse of what modern England is like they will discover that England has a very broken, belated and inadequate sense of having an obligation to Europe, but no sort of sense whatever of having any obligation to Teutonism.

This is the last and strongest of the Prussian qualities we have here considered. There is in stupidity of this sort a strange slippery strength: because it can be not only outside rules but outside reason. The man who really cannot see that he is contradicting himself has a great advantage in controversy; though the advantage breaks down when he tries to reduce it to simple addition, to chess, or to the game called war. It is the same about the stupidity of the one-sided kinship. The drunkard who is quite certain that a total stranger is his long-lost brother, has a greater advantage until it comes to matters of detail. “We must have chaos within” said Nietzsche, “that we may give birth to a dancing star.”

In these slight notes I have suggested the principal strong points of the Prussian character. A failure in honour which almost amounts to a failure in memory: an egomania that is honestly blind to the fact that the other party is an ego; and, above all, an actual itch for tyranny and interference, the devil which everywhere torments the idle and the proud. To these must be added a certain mental shapelessness which can expand or contract without reference to reason or record; a potential infinity of excuses. If the English had been on the German side, the German professors would have noted what irresistible energies had evolved the Teutons. As the English are on the other side, the German professors will say that these Teutons were not sufficiently evolved. Or they will say that they were just sufficiently evolved to show that they were not Teutons. Probably they will say both. But the truth is that all that they call evolution should rather be called evasion. They tell us they are opening windows of enlightenment and doors of progress. The truth is that they are breaking up the whole house of the human intellect, that they may abscond in any direction. There is an ominous and almost monstrous parallel between the position of their over-rated philosophers and of their comparatively under-rated soldiers. For what their professors call roads of progress are really routes of escape.

LETTERS TO AN OLD GARIBALDIAN

Italy, twice hast thou spoken; and time is a thirst for the third.

–SWINBURNE.

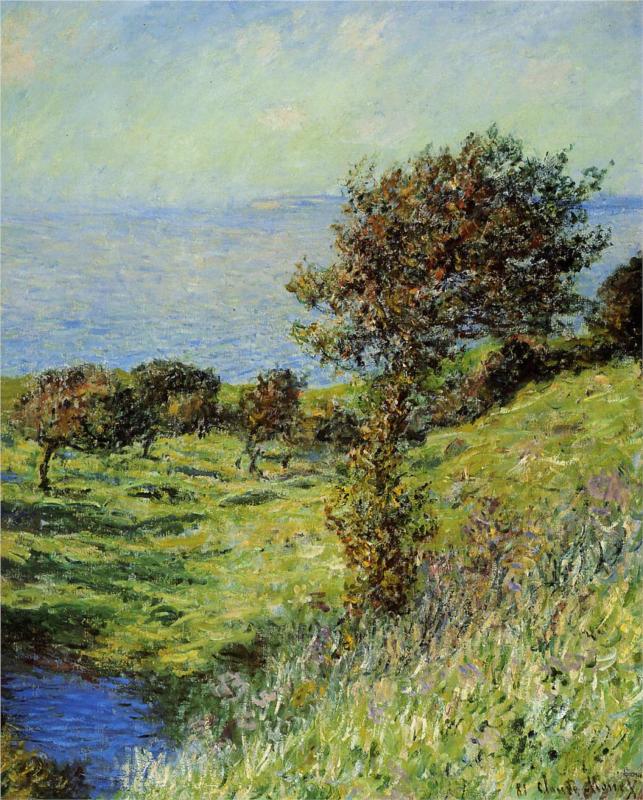

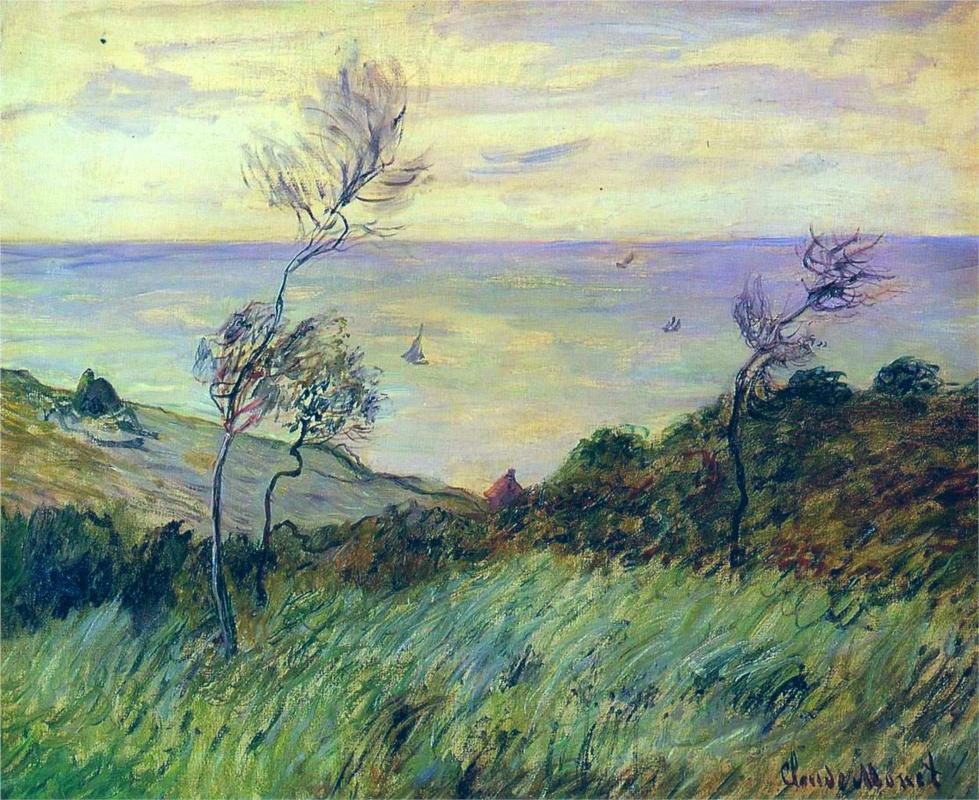

My Dear—It is a long time since we met; and I fear these letters may never reach you. But in these violent times I remember with a curious vividness how you brandished a paintbrush about your easel when I was a boy; and how it thrilled me to think that you had so brandished a bayonet against the Teutons–I hope with the same precision and happy results. Round about that period, the very pigments seemed to have some sort of picturesque connection with your national story. There seemed to be something gorgeous and terrible about Venetian Red; and something quite catastrophic about Burnt Sienna. But somehow or other, when I saw in the street yesterday the colours on your flag, it reminded me of the colours on your palette.

You need not fear that I shall try to entangle you or your countrymen in the matters which it is for Italians alone to decide. You know the perils of either course much better than I do. Italy, most assuredly, has no need to prove her courage. She has risked everything in standing out that she could risk by coming in. The proclamations and press of Germany make it plain that the Germans have risen to a height of sensibility hardly to be distinguished from madness. Supposing the nightmare of a Prussian victory, they will revenge themselves on things more remote than the Triple Alliance. There was a promise of peace between them and Belgium; there was none between them and England. The promise to Belgium they broke. The promise of England they invented. It is called the Treaty of Teutonism. No one ever heard of it in this country; but it seems well known in academic circles in Germany. It seems to be something, connected with the colour of one’s hair. But I repeat that I am not concerned to interfere with your decision, save in so far as I may provide some materials for it by describing our own.

For I think the first, perhaps the only, fruitful work an Englishman can do now for the formation of foreign opinion is to talk about what he really understands, the condition of British opinion. It is as simple as it is solid. For the first time, perhaps, what we call the United Kingdom entirely deserves its name. There has been nothing like such unanimity within an Englishman’s recollection. The Irish and even the Welsh were largely pro-Boers, so were some of the most English of the English. No one could have been more English than Fox, yet he denounced the war with Napoleon. No one could be more English than Cobden, but he denounced the war in the Crimea. It is really extraordinary to find a united England. Indeed, until lately, it was extraordinary to find a united Englishman. Those of us who, like the present writer, repudiated the South African war from its beginnings, had yet a divided heart in the matter, and felt certain aspects of it as glorious as well as infamous. The first fact I can offer you is the unquestionable fact that all these doubts and divisions have ceased. Nor have they ceased by any compromise; but by a universal flash of faith–or, if you will, of suspicion. Nor were our internal conflicts lightly abandoned; nor our reconciliations an easy matter. I am, as you are, a democrat and a citizen of Europe; and my friends and I had grown to loathe the plutocracy and privilege which sat in the high places of our country with a loathing which we thought no love could cast out. Of these rich men I will not speak here; with your permission, I will not think of them. War is a terrible business in any case; and to some intellectual temperaments this is the most terrible part of it. That war takes the young; that war sunders the lovers; that all over Europe brides and bridegrooms are parting at the church door: all that is only a commonplace to commonplace people. To give up one’s love for one’s country is very great. But to give up one’s hate for one’s country, this may also have in it something of pride and something of purification.

What is it that has made the British peoples thus defer not only their artificial parade of party politics but their real social and moral complaints and demands? What is it that has united all of us against the Prussian, as against a mad dog? It is the presence of a certain spirit, as unmistakable as a pungent smell, which we feel is capable of withering all the good things in this world. The burglary of Belgium, the bribe to betray France, these are not excuses; they are facts. But they are only the facts by which we came to know of the presence of the spirit. They do not suffice to define the whole spirit itself. A good rough summary is to say that it is the spirit of barbarism; but indeed it is something worse. It is the spirit of second-rate civilisation; and the distinction involves the most important differences. Granted that it could exist, pure barbarism could not last long; as pure babyhood cannot last long. Of his own nature the baby is interested in the ticking of a watch; and the time will come when you will have to tell him, if you only tell him the wrong time. And that is exactly what the second-rate civilisation does.

But the vital point is here. The abstract barbarian would copy. The cockney and incomplete civilisation always sets itself up to be copied. And in the case here considered, the German thinks that it is not only his business to spread education, but to spread compulsory education. “Science combined with organisation,” says Professor Ostwald of Berlin University, “makes us terrible to our opponents and ensures a German future for Europe.” That is, as shortly as it can be put, what we are fighting about. We are fighting to prevent a German future for Europe. We think it would be narrower, nastier, less sane, less capable of liberty and of laughter, than any of the worst parts of the European past. And when I cast about for a form in which to explain shortly why we think so, I thought of you. For this is a matter so large that I know not how to express it except in terms of artists like you, in the service of beauty and the faith in freedom. Prussia, at least cannot help me; Lord Palmerston, I believe, called it a country of damned professors. Lord Palmerston, I fear, used the word “damned” more or less flippantly. I use it reverently.

Rome, at her very weakest, has always been a river that wanders and widens and that waters many fields. Berlin, at its strongest, will never be anything but a whirlpool, which seeks its own centre, and is sucked down. It would only narrow all the rest of Europe, as it has already narrowed all the rest of Germany. There is a spirit of diseased egoism, which at last makes all things spin upon one pin-point in the brain. It is a spirit expressed more often in the slangs than in the tongues of men. The English call it a fad. I do not know what the Italians call it; the Prussians call it philosophy.

Here is the sort of instance that made me think of you. What would you feel first, let us say, if I mentioned Michael Angelo? For the first moment, perhaps, boredom: such as I feel when Americans ask me about Stratford-on-Avon. But, supposing that just fear quieted, you would feel what I and every one else can feel. It might be the sense of the majestic hands of Man upon the locks of the last doors of life; large and terrible hands, like those of that youth who poises the stone above Florence, and looks out upon the circle of the hills. It might be that huge heave of flank and chest and throat in “The Slave,” which is like an earthquake lifting a whole landscape; it might be that tremendous Madonna, whose charity is more strong than death. Anyhow, your thoughts would be something worthy of the man’s terrible paganism and his more terrible Christianity. Who but God could have graven Michael Angelo; who came so near to graving the Mother of God?

German culture deals with the matter as follows:–”Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475–1564).–(=Bernhard) ancestor of the family, lived in Florence about 1210. He had two sons, Berlinghieri and Buonarrota. By this name recurring frequently in later generations, the family came to be called. It is a German name, compounded of Bona (=Bohn) and Hrodo, Roto (=Rohde, Rothe) Bona and Rotto are cited as Lombard names. Buonarotti is perhaps the old Lombard Beonrad, corresponding to the word Bonroth. Corresponding names are Mackrodt, Osterroth, Leonard.” And so on, and so on, and so on. “In his face he has always been well-coloured . . . the eyes might be called small rather than large, of the colour of horn, but variable with ‘flecks’ of yellow and blue. Hair and beard are black. These particulars are confirmed by the portraits. First and foremost take the portrait of Bugiardini in Museo Buonarotti. Here comes to view the ‘flecked’ appearance of the iris, especially in the right eye. The left may be described as almost wholly blue.” And so on, and so on, and so on. “In the Museo Civico at Pavia, is a fresco likeness by an unknown hand, in which this fresh red is distinctly recognisable on the face. Taking all these bodily characteristics into consideration, it must be said from an anthropological point of view that though originally of German family he was a hybrid between the North and West brunette race.”

Would you take the trouble to prove that Michael Angelo was an Italian that this man takes to prove that he was a German? Of course not. The only impression this man (who is a recognised Prussian historian) produces on your mind or mine is that he does not care about Michael Angelo. For you, being an Italian, are therefore something more than an Italian; and I being an Englishman, something more than an Englishman. But this poor fellow really cannot be anything more than a Prussian. He digs and digs to find dead Prussians, in the catacombs of Rome or under the ruins of Troy. If he can find one blue eye lying about somewhere, he is satisfied. He has no philosophy. He has a hobby, which is collecting Germans. It would probably be vain for you and me to point out that we could prove anything by the sort of ingenuity which finds the German “rothe” in Buonarotti. We could have great fun depriving Germany of all her geniuses in that style. We could say that Moltke must have been an Italian, from the old Latin root mol–indicating the sweetness of that general’s disposition. We might say Bismarck was a Frenchman, since his name begins with the popular theatrical cry of “Bis!” We might say Goethe was an Englishman, because his name begins with the popular sporting cry “Go!” But the ultimate difference between us and the Prussian professor is simply that we are not mad.

The father of Frederick the Great, the founder of the more modern Hohenzollerns, was mad. His madness consisted of stealing giants; like an unscrupulous travelling showman. Any man much over six foot high, whether he were called the Russian Giant or the Irish Giant or the Chinese Giant or the Hottentot Giant, was in danger of being kidnapped and imprisoned in a Prussian uniform. It is the same mean sort of madness that is working in Prussian professors such as the one I have quoted. They can get no further than the notion of stealing giants. I will not bore you now with all the other giants they have tried to steal; it is enough to say that St. Paul, Leonardo da Vinci, and Shakespeare himself are among the monstrosities exhibited at Frederick-William fair–on grounds as good as those quoted above. But I have put this particular case before you, as an artist rather than an Italian, to show what I mean when I object to a “German future for Europe.” I object to something which believes very much in itself, and in which I do not in the least believe. I object to something which is conceited and small-minded; but which also has that kind of pertinacity which always belongs to lunatics. It wants to be able to congratulate itself on Michael Angelo; never to congratulate the world. It is the spirit that can be seen in those who go bald trying to trace a genealogy; or go bankrupt trying to make out a claim to some remote estate. The Prussian has the inconsistency of the parvenu; he will labour to prove that he is related to some gentleman of the Renaissance, even while he boasts of being able to “buy him up.” If the Italians were really great, why–they were really Germans; and if they weren’t really Germans, well then, they weren’t really great. It is an occupation for an old maid.

Three or four hundred years ago, in the sad silence that had followed the comparative failure of the noble effort of the Middle Ages, there came upon all Europe a storm out of the south. Its tumult is of many tongues; one can hear in it the laughter of Rabelais, or, for that matter, the lyrics of Shakespeare; but the dark heart of the storm was indeed more austral and volcanic; a noise of thunderous wings and the name of Michael the Archangel. And when it had shocked and purified the world and passed, a Prussian professor found a feather fallen to earth; and proved (in several volumes) that it could only have come from a Prussian Eagle. He had seen one–in a cage.

Yours–,

G.K. CHESTERTON.

My Dear—The facts before all Europeans to-day are so fundamental that I still find it easier to talk about them to you as to an old friend, rather than put it in the shape of a pamphlet. In my last letter I pointed out two facts which are pivots. The first is that, to any really cultured person, Prussia is second-rate. The second is that to almost any Prussian, Prussia is really first-rate; and is prepared, quite literally, to police the rest of the world.