An Ecclesiastical History To The 20th Year Of The Reign Of Constantine by Eusebius

PREFACE

IF history he accurately defined as philosophy teaching by examples, no branch of it can contain lessons of philosophy so interesting and important as the history of the church. Taking the terms in the most comprehensive sense, church history for more than four thousand years is matter of express revelation. It is the history of man and of Divine providence in their most momentous aspects, and has therefore been selected from the common trains of history to form the subject of an inspired chronicle. The Acts of the Apostles complete the annals; thenceforth ecclesiastical history flows from a different origin. It is written by the pen of man, and therefore marked by errors and defects; but the thought of ecclesiastical writers being, in a manner, continuators of the record of scripture,—followers in the train of evangelists and apostles,—while it is calculated deeply to impress every author who enters on this field of literature with a sense of his personal responsibility, must also impart, in the estimation of the reader, a degree of interest to such compositions that no others can possess.

Of all the periods of church history, the first three or four centuries are in many respects the most important. They exhibit to us the early struggles and triumphs of Christianity, the means by which it was disseminated, and the extent to which it prevailed; the sufferings and heroism of martyrs—the development of theology as a science—the effects of false philosophy upon the simple truths of revelation—the activity of the human mind in aiming at discoveries beyond its reach, and the forms of government and polity which the early churches assumed; subjects worthy the examination not only of the Christian, but of the philosopher.

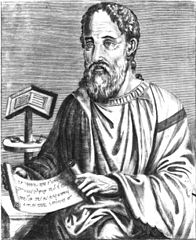

While ecclesiastical history in general, now receives a growing measure of attention, the period just specified is the subject of most minute and critical investigation. Whatever throws light upon the character of those eventful times, possesses at the present day more than ordinary value. But though most of the ecclesiastical writers of that age contain information relative to the history of Christianity, no professed historian of that period remains except EUSEBIUS. Hegesippus, who lived in the second century, wrote a history of the church in five books, but the only fragments handed down to us have been preserved by Eusebius. He is then, truly, the father of ecclesiastical history, the only compiler we have of a narrative of Christian affairs for nearly three hundred years after the close of the inspired annals. Venerable for his antiquity, he is valuable as an historian. The extensive learning he possessed formed one leading qualification for undertaking such a work, and the extent to which he availed himself of all existing documents, connected with his subject, is apparent to every reader of his history. And even though, according to the learned Scaliger, his judgment should not be equal to his research, yet all must admit that the mass of historical materials he has bequeathed to the church constitutes a most precious legacy—that indeed excess in their accumulation is an error on the safe side, and that it is much more to be regretted that our author did not make a still larger collection of documents and extracts, than that he should have included in his compilation some of doubtful authority.

Eusebius closes his history with the year 324, where the thread of his narrative is taken up by Socrates Scholasticus and Sozomen, who continue it down to the year 439. Theodoret forms a kind of supplement to these, beginning with the same year as Sozomen, 324, and carrying it to the year 429. Evagrius again resumes the history at the year 439, and proceeds with it to the year 594. These form a cabinet of ecclesiastical history for the first six centuries. The worth of works of this kind, with all their imperfections, will be fully appreciated by every thoughtful mind. Modern compilations may be more philosophical, critical, and elegant; the matter may be more carefully collected, condensed into a smaller space, arranged in a better form, and expressed in more polished language, but the independent investigator will wish to examine for himself the sources whence they have been derived, and form a judgment from the perusal of original documents.

Eusebius is by far the most valuable of those we have mentioned, and who that takes an interest in historical studies, while incompetent to the perusal of our author in the original, but will gladly avail himself of an opportunity of becoming acquainted with him through the medium of a translation? Besides several versions in Latin, French, and German, there are three in English, published in this country; one by Hanmer, another published at Cambridge, 1683, without a name, and a third, incorporated by Parker in his abridgement of the works of the ecclesiastical writers. Yet these do not preclude the propriety, and indeed desirableness, of publishing a new translation, more correct in its renderings, and more suited in its style to the taste and character of the age.

A translation, therefore, by an American Episcopal divine, the Reverend C. F. Crusè, D.D., has been adopted in the present volume, and is now submitted to the public.

Speaking of his own labours, he says, “Whether the present translator has succeeded in presenting his author to the public in a costume that shall appear worthy of the original, must be left to the judgment of others. He is not so confident as to presume his labour is here immaculate, and a more frequent revision of the work may suggest improvements which have thus far escaped him. Some allowances are also due to a work like this, which may not obtain in those of a different description. The translator does not stand upon the same ground as one who renders a work of elegance and taste, from profane antiquity. The latter leaves more scope for the display of genius and taste. The great object of the former is to give a faithful transcript of his author’s statement, that the reader may derive, if possible, the same impression that he would from the original, in case it were his vernacular language. He is not at liberty to improve his author, whatever may be the occasional suggestions of elegance or taste, for there is scarcely any such improvement but what involves the fidelity of the version. The more experienced reader and critic may, perhaps, discover instances where the translator might perhaps have been more easy, without sacrificing much of the meaning; and the present version is not without passages where perhaps a little liberty might have obviated an apparent stiffness in the style. But the translator has sometimes preferred the latter, to what appeared a sacrifice of the sense.

“The office of a translator, like that of a lexicographer, is an ungrateful office. Men who have no conception of the requisites for such a task, who measure it by the same rough standard that they do a piece of manual labour, are apt to suppose he has nothing to do but to travel on from word to word, and that it amounts at last to scarcely more than a transcription of what is already written in his own mind. In the estimate which is thus made, there is little credit given, for the necessary adaptation of the style and phraseology to that of the original,—no allowance for that degree of judgment, which the interpreter must constantly exercise in order to make his version tell what its original says. And yet, with all this, there is generally discrimination enough to mark what may be happily expressed; but by a singular perversion, such merit is sure to be assigned to the original work, whilst the defects are generally charged to the account of the translator. Some, ignorant of the limits of the translator’s office, even expect him to give perfection to his author’s deficiencies, and if he fails in this, he is in danger of having them heaped upon himself.

“To preclude any unwarrantable expectations, the translator does not pretend to more in the present work, than to give a faithful transcript of the sense of his author. Occasionally, he thinks he has expressed that sense with more perspicuity than his original, and wherever the ambiguity seemed to justify it, it has been done, not with a view to improve his author, but to prevent mistaking his meaning.”

The version is from the accurate Greek text of Valesius, a learned French civilian, to whom the palm is due as an editor and Latin translator of Eusebius and the other ecclesiastical historians we have mentioned. The edition used was the splendid one by Reading, printed at Cambridge, 1720.

In this edition the whole of the American translation has undergone revision; and the present editor hopes that he has been successful in correcting some few errors which had been admitted into the renderings, and some obscurities and inelegant peculiarities of diction that had disfigured the style. He has also prefixed to the History, Parker’s translation of the life of Eusebius, by Valesius, having carefully compared it with the original, and corrected it.

The few notes introduced in the work, are, with two or three exceptions, by the American translator.

The whole forms a volume which it is hoped will be found peculiarly acceptable to the public, in an age distinguished by an increasing taste for the study of Ecclesiastical History.

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running