A Hstory Of The Councils Of The Church Volumes 1 to 5 by Charles Joseph Hefele D.D.

CHAPTER II

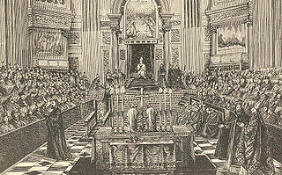

THE SEVENTH ŒCUMENICAL SYNOD AT NICÆA, A.D. 787

SEC. 345. The Empress Irene makes preparations for the Convocation of an Œcumenical Synod

IRENE was recognised as guardian of her son, the new Emperor, Constantine VI. Porphyrogenitus, who was only ten years old, and at the same time regent of the Empire. After only fourteen days, however, a party of senators and high officials resolved to proclaim Prince Nicephorus (brother of Leo IV.; see p. 339) as Emperor. Irene discovered the conspiracy in good time, took the ringleaders, and, after having them shorn and scourged, banished them to several islands. Nicephorus, however, and his brothers were required to take holy orders, and on the following Christmas (780) to publicly administer the sacraments, that all the people might learn what had taken place. On the same festival, Irene restored to the great church the precious crown which her husband had taken away. So also the body of S. Euphemia was solemnly brought back to Chalcedon from its place of concealment at Lemnos (see p. 326); and from this time, says Theophanes (p. 704), the pious were allowed without hindrance to worship God and to renounce heresy, and also the monasteries revived, that is to say, each one was allowed, if his inclination and conscience urged him thereto, again to venerate the images, and in particular this was the case with restored monks, among whom Abbot Plato, uncle of Theodore Studites, was peculiarly distinguished. Abbot Plato distinguished himself also later on, at the preparatory Synod of the year 786, by defending the images, as his ancient biographer relates. But Baronius (ad ann. 780, 7), using the inaccurate translation of this Vita Platonis by Sirlet, has imagined a Conciliabulum of the enemies of images at Constantinople, A.D. 780, an error corrected already by Pagi (ad ann. 780, 3, 4).

There is no doubt that Irene already thought of the complete restoration of the veneration of images, and at the same time of the resumption of Church communion with the rest of Christendom. That Pope Hadrian I. exhorted her continually to this, he says himself (see below, p. 351); but that Irene expected from this favourable results in regard to the possible winning back of Italy, is the supposition of later scholars. But the carrying out of this plan had to be put off so much the more on account of the wars with the Arabs and Slavonians, since with the military, among the officers who had been brought up under Copronymus, iconoclasm still counted its most numerous adherents. But after a peace, which was certainly inglorious, had been concluded with the Arabs, whilst, on the other hand, the Slavonians were gloriously overcome and made tributary, then it was possible to consider the ecclesiastical question more steadily. At the same time, Irene had brought about a betrothal between her son, the young Emperor, and Notrude, the daughter of Charles the Great, who was from seven to eight years of age, and therefore had to regard the restoration of ecclesiastical union with the West as requisite, or at least as desirable. The two men who specially assisted the Empress in this were Paul, until now patriarch, and his successor Tarasius; the former by the way and manner of his resignation, the other by the condition which he laid down on his assumption of the see. It is very probable that the Empress had come to an agreement with Tarasius as to the course to be taken; whilst it is less probable that any previous settlement had been made with the Patriarch Paul. When the latter fell ill in August 784, he experienced such violent pains of conscience on account of his behaviour in the matter of the images, particularly on account of the oath at his entrance upon office, that he actually laid down his office, left the patriarchal palace, betook himself to the monastery of S. Florus, and put on the monastic habit, August 31, 784. Theophanes says (p. 708) that he did this without any previous knowledge on the part of the Empress, and that as soon as she obtained intelligence of it she went immediately with Her son into the monastery of S. Florus, in order to interrogate the patriarch, with complaints and reproaches, as to the reason of his withdrawal. He answered with tears: “Oh, that I had never occupied the see of Constantinople, since this church is tyrannised over, and is separated from the rest of Christendom.” Thereupon Irene, returning, sent several senators and patricians to Paul, that they might hear the same from him, and through his confessions might become inclined to the restoration of the images. He declared to them: “Unless they call an Œcumenical Synod and root out the prevailing error, you cannot be saved.” To their reproach, “But why then did you promise, in writing, at your consecration never to consent to the veneration of images?” he replied, “That is the very cause of my tears, and this has driven me to do penance and to pray God for His forgiveness.” Amid such conversations Paul died, deeply lamented by the Empress and the people, for he had been pious and very beneficent. From that time many spoke openly in defence of the images.

Soon afterwards the Empress held a great assemblage of the people in the palace Magnaura, and said: “You know what the Patriarch Paul has done. Although he took the monastic habit, we should nevertheless have refused to accept his resignation if he had not died. Now it is necessary to give him a worthy successor.” All exclaimed that there was none more worthy than the imperial secretary, Tarasius, who was still a layman. The Empress replied: “We have also selected him as patriarch, but he does not consent. He is now himself to enter and speak to the people.” Tarasius then addressed the meeting in a detailed speech, speaking of the care of the Emperors (namely, Irene and her son) for religion, declared his own unworthiness and the like. But particularly, he proceeded, would he guard against this, that the Byzantine kingdom should be separated in religion from the West and also from the East, and should from all sides receive anathema. He therefore prayed the Emperors—and all the people should support his prayer—to summon an Œcumenical Synod for the restoration of ecclesiastical unity.

This speech is found in all completeness both in Theophanes (l.c. pp. 710–713) and in the preliminary Acts of the seventh Œcumenical Council, only with this difference, that Theophanes maintains: All present shouted approval to Tarasius, and with him demanded the summoning of an Œcumenical Synod; whilst it is added in the synodal Acts: “Some who lacked intelligence opposed.” This statement, confirmed by the fact that, at the beginning, the military dispersed the Council which was subsequently called, is also in agreement with the biographer of Tarasius (Ignatius), who adds that, however, the right prevailed. Tarasius was consecrated patriarch at Christmas, 784. Almost everywhere we read the statement, referred to Theophanes, that he immediately sent a Synodica and declaration of faith to Rome and to the other patriarchs; but even Pagi remarked (ad ann. 784, 2) that the word confestim occurred indeed in the Latin translation of the chronography of Theophanes (l.c. p. 713), but was not justified by the original Greek text. It is, however, most probable that Tarasius, soon after ascending the throne, renewed intercourse with the other patriarchs. His letter, addressed “to the archpresbyters and presbyters of Antioch, Alexandria, and the holy city” (Jerusalem), an Inthronistica (without date), is preserved among the Acts of the third session of Nicæa, and relates at the beginning, how he, although still a layman, had been constrained to accept the sacred office by the bishops and clergy. The other bishops were therefore requested to support him as fathers and brethren, for a spiritual conflict lay before him. But, in possession of unconquerable truth, and supported by his brethren, he would overcome the babblers. As, however, it was an ancient, even an essentially apostolic tradition, that a newly appointed bishop should set forth his confession of faith, he would also now confess what he had learnt from his youth. After a not very full confession of faith, in which anathema is pronounced upon Pope Honorius, he passes over to the question of the images with the words: “This sixth Synod I accept with all the dogmas pronounced by it, and all the canons promulgated by it, among them that which runs: In some representations of the sacred images there is found the figure of the Lamb; but we decide that Christ shall be represented in human form.” He cites here canon 82 of the Quinisext (see p. 234), and ascribes its canons to the sixth Œcumenical Synod, which, as is well known, promulgated no canons. He then proceeds: “What was afterwards superfluously chattered and babbled (i.e. the decrees of the false Synod of the year 754), I reject, as you also have done; and as the pious and faithful Emperors have granted the request for the holding of an Œcumenical Synod, you will not refuse your co-operation in order to restore again the unity of the Church. Each of you (patriarchs) will therefore please to send two representatives, with a letter, and communicate his view on this matter as it has been given him by God. I have also petitioned the bishop of Old Rome for the same,” etc.

The letter addressed to the Pope, to which Tarasius here refers, and of which Theophanes also speaks (l.c. p. 713), we no longer possess, but we know it from the answer of Hadrian I. and from the remark of the papal legates at the seventh Council, “that the Pope had also received such a letter, τοιαῦτα γράμματα” (thus in its principal contents corresponding with the letter of Tarasius to the Oriental patriarchs). The conveyance of this letter to Rome was committed by Tarasius to his priest and representative (apocrisiar) Leo; but the Court also sent a Divalis Sacra to the Pope. In the superscription, Irene placed, as in all the documents of this period (she altered it afterwards), the name of her son before her own. In this letter she starts with the statement that the secular and spiritual powers both proceeded from God, and therefore were bound in common to rule the peoples entrusted to them in accordance with the divine will; and then proceeds: “Your Holiness knows what has been undertaken here in Constantinople by previous governors against the venerable images. May it not be reckoned to them by God! They have led astray all the people here in Constantinople, and also the East (as far as it was under Byzantium), until God called us to the government,—us who seek in truth the honour of God, and desire to hold that fast which has been handed down by the apostles and the holy doctors. We therefore, after consultation with our subjects and the most learned priests, resolved upon the summoning of an Œcumenical Synod, and we pray—yea, God Himself, who wills to lead all men to the truth, prays—that your fatherly Holiness will yourself appear at this Synod, and come hither to Constantinople, for the confirmation of the ancient tradition in regard to the venerable images. We will receive your Holiness with all honours, provide you with all that is necessary, and provide for your worthy return after the work is accomplished. In case, however, your Holiness should be unable personally to come hither, be pleased to send venerable and learned representatives, that, by a Synod, the tradition of the holy Fathers may be confirmed and the tares rooted out, and that henceforth there may be no more division in the Church. Moreover, we have called here to us Bishop Constantine of Leontium (in Sicily), who is also known to your fatherly Holiness, have conversed with him by word of mouth, and have sent him to you with this edict (venerabilis jussio). When he has come to you, be pleased to give him your answer soon, that he may return to us and inform us on what day you will depart from Rome. He will also bring hither with him the bishop of Naples. We have commanded our representative in Sicily to take care to provide for your peace and dignity.

This letter, which we now possess only in the Latin translation by Anastasius Bibliothecarius, is dated IV. Kal. Sept. Indict vii., i.e. August 29, 784. As, however, we saw above that Tarasius was made patriarch on December 25, 784, according to this the imperial Sacra would have been despatched four months before his elevation. This is contradicted alike by Theophanes (l.c. p 713) and by the answer of Pope Hadrian. Quite arbitrary and improbable, however, is the supposition of Christian Lupus, that the Court of Byzantium sent two letters, one after the other, to the Pope, the one just noticed and a later one, and that Pope Hadrian sent two answers, and that only his second answer is extant. Pagi (ad ann. 785, 3) opposed this hypothesis, and drew attention to the fact that the seventh Œcumenical Synod and the ancient collectors of its Acts knew of only one imperial letter to the Pope, and of only one answer from Hadrian. At the same time, that assumption was only a desperate way of escape, in order to get out of the chronological difficulty which lies in the date given above. But this is easily got rid of, if with Pagi we read Indict viii., according to which the imperial Sacra was written in August 785, a date which suits quite well. That such a correction has to be made, Walch (S. 532) had also seen from Pagi; but he went wrong about a full year, because he made the Indictio vii. to begin with September 1, 782, and the 8th with September 1, 783. Moreover, IV. Kal. Sept. is not August 27, as he supposes, but August 29.

Objections to the genuineness of this imperial letter to the Pope were raised by the Gallican Edmond Richer and the Protestants Spanheim junior, and Basnage, but even Walch (S. 532) found them untenable.

When the envoy of Tarasius, his priest and apocrisiar Leo, arrived in Sicily, the regent of that place, at the imperial command, gave him, as companions, Bishop Theodore of Catanea and the deacon Epiphanius (afterwards deputy of the archbishop of Sardinia at the Council of Nicæa), in order to convey to Rome, in common with him, the imperial jussio (two jussiones, indeed, the one regarding the Synod and the other on the recognition of Tarasius). We learn this from the minutes of the second session of Nicæa. Bishop Constantine of Leontium, on the contrary, who had been sent by Irene, no longer appears, and even Hadrian makes no reference to him in the letter which he sent in reply to the Court. We may perhaps assume that Bishop Constantine fell sick on the journey from Constantinople to Sicily, and that after the regent had communicated information of this to the Court, Bishop Theodore and the deacon Epiphanius were named imperial envoys in the place of Constantine.

Pope Hadrian, on October 27, 785, answered the two rulers in a very extensive Latin letter. A Greek translation of this was read in the second session of the Nicene Council, and is still extant. But in this reading, as Anastasius testifies, with the consent of the legate, they cut off nearly the last quarter, because in it, as we shall see, Tarasius was blamed by the Pope, and this might have been abused by his opponents and those of the Council so as to do an injury to the good cause itself. When Anastasius, on undertaking the translation of the Acts of Nicæa, remarked this, he inserted in his collection the Latin original of the letter of Hadrian, which he naturally found in Rome, and we see from this that, in other places also, the Greek translation contains arbitrary alterations. In the collections of the Councils, it is found side by side with the original Latin text communicated by Anastasius; in the same way as elsewhere, there the translation of Anastasius is given along with the original Greek text.

Pope Hadrian, in this letter, first of all expresses his joy at the return of the two rulers to orthodoxy and at their resolution to restore the veneration of images. If they carried this through, they would be a new Constantine and a second Helena, especially if, like them, they honoured the successor of Peter and the Roman Church. The Prince of the apostles, to whom God had committed the power of binding and loosing, would therefore protect them, and subject all the barbarous nations to them. The sacred authority (Holy Scripture) declared the height of his dignity, and what reverence should be given by all Christians to the Summa sedes of Peter. God had placed this Claviger of the kingdom of heaven as princeps over all; and Peter had left his primacy, by divine command, to his successors, and the tradition of these testified for the veneration of the images of Christ, His Mother, the apostles, and all saints. Pope Silvester, in particular, testifies that from the time when the Christian Church began to enjoy rest and peace, the churches had been adorned with pictures. An old writing related: “When Constantine decided to adopt the faith, there appeared to him by night Peter and Paul, and said to him: Because thou hast put an end to thy misdeeds, we are sent by Christ the Lord to counsel thee how thou canst regain thy health. In order to escape from thy persecutions, Bishop Silvester of Rome has hidden himself with his clergy on Mount Soracte. Call him to thee, and he will show thee a pool, and when he has dipped thee in it for the third time, thy leprosy will immediately depart. In gratitude for this, thou must honour the true God, and order that in the whole Empire then the churches should be restored. Immediately after awaking, Constantine sent to Silvester, who, with his clergy, was employed in reading and prayer on a property on Soracte. When he saw the soldiers, he thought he was about to be led to martyrdom, but Constantine received him in a very friendly manner, and told him of the vision of the night, adding: Who, then, are these gods Peter and Paul? Silvester corrected this error, and, at the wish of the Emperor, had a picture of the two apostles brought up, on which Constantine cried aloud: Yes, these he had seen, and the vision therefore came from the Holy Spirit.” This proved the ancient use of images in the Church, and many heathens had already been converted by seeing them. The Emperor Leo the Isaurian had been the first who had been misled and had proclaimed war on the images in Greece, and had caused great vexation. In vain had Gregory II. and III. exhorted him, and Pope Zacharias, Stephen II., Paul, and Stephen III., the Emperors succeeding him, to restore the images. He himself also, Hadrian, had continually put forward the same request to the present rulers, and renewed it with all his might, so that, as the rulers had already done it, their subjects might also return to orthodoxy, and become “one flock and one fold,” since then the images would be venerated again by all the faithful in the whole world.

The Pope further defends the veneration of images, which had been falsely given out as a deification of them. From the very beginning of human history, he said, God had not rejected what men themselves had contrived in order to testify their reverence for Him, thus the sacrifice of Abel, the altar of Noah, the memorial stone of Jacob (Gen. 28.). Thus Jacob, of his own impulse, kissed the top of the staff of his own son Joseph (Heb. 11:21, according to the Vulgate [adoravit fastigium virgæ ejus]); but not in order to do honour to the staff, but to testify his love and reverence for the bearer of the staff. In the same manner, love and reverence were paid by Christians, not to images and colours, but to those in whose honour they were set up. Thus Moses had cherubim prepared for the honour of God, and set up a brazen serpent as a sign (type of Christ). The prophets, too, spoke of the adornment of the house of God and of the reverence and representation of the countenance of God (Ps. 25[26]:8, 26[27]:8, 44[45]:13, 4[5]:7); and Augustine said: Quid est imago Dei, nisi vultus Dei? Then follow beautiful passages from Gregory of Nyssa, Basil, Chrysostom, Cyril, Athanasius, Ambrose, Epiphanius, Stephen of Bostra, and Jerome. Supporting himself upon these patristic and biblical passages, he cast himself at the feet of the rulers, and prayed them that they would restore the images again in Constantinople and in the whole of Greece, and follow the tradition of the holy Roman Church, in order to be received into the arms of this holy, catholic, apostolic, and blameless Church.

So far the papal letter was read aloud at Nicæa; but Anastasius communicated, along with his translation of the Nicene Acts, a further portion of the letter, which is as follows: “If, however, the restoration of the images cannot take place without an Œcumenical Synod, the Pope will send envoys, and in their presence, before everything else, must that false assembly (of the year 754) be anathematised, because it was held without the apostolic see, and had drawn up wicked decrees against the images. In like manner must the Emperor, the Empress his mother, the patriarch, and the senate, in accordance with ancient custom, transmit to the Pope a pia sacra (document), in which they promise by oath (at the Synod to be held) to be impartial, and to do no violence to the papal legate or any priest, but, on the contrary, in every way to honour and uphold them, and if no union could be attained, to provide in the most friendly manner for their return. Moreover, if the rulers would really return to the orthodox faith of the holy catholic Roman Church, then they must also again restore completely the patrimonia Petri (withdrawn by the previous Emperors) and the rights of consecration, which belonged to the Roman Church over the archbishops and bishops of its whole diocese (patriarchate) according to ancient right (cf. p. 304). The Roman see had the primacy over all the churches of the world, and to that belonged the confirmation of Synods. Hadrian, however, had greatly wondered that, in the imperial letter which had requested the confirmation of Tarasius, the latter was named universalis patriarcha. He did not know whether this had been written per imperitiam, aut schisma vel hæresim iniquorum; but the Emperors should no longer use this expression, for it was in opposition to the traditions of the Fathers, and if it should be meant by this, that this universalis stood even above the Roman Church, then would he be a rebel against the sacred Synods and an evident heretic. If he were universalis, then he must necessarily also possess the primacy which was left by Christ to Peter, and by him to the Roman Church. If any one should call Tarasius an universalis patriarcha in this sense, which, however, he did not believe, he would be a heretic and a rebel against the Roman Church. Tarasius had, in accordance with ancient custom, sent a Synodica to the Pope, and he rejoiced at the confession of the orthodox faith which was contained in it in regard also to the holy images, but it had grieved him that Tarasius had, from a layman and a booted soldier (apocaligus), been suddenly made patriarch. This was in contradiction to the sacred canons, and the Pope would not have been able to assent to his consecration had he not been a faithful helper in the restoration of the sacred images. The whole of Christendom would rejoice over the restoration of the images, and the Emperors, under the protection of S. Peter, would then triumph over all barbarous peoples, just as Charles, the King of the Franks and Lombards, and patrician of Rome (the Pope’s filius et spiritualis compater), who, following in all things the admonitions of the Pope, subjected to himself the barbarous nations of the West, presented to the Church of S. Peter many estates, provinces, and cities, and had given back that which had been seized by the faithless Lombards. He had also offered to the Church much money and silver pro luminariorum concinnatione, and free alms to the poor, so that his royal remembrance was secured for all the future. Finally, the Emperors were requested to give a friendly reception to the bearers of this letter, the Roman Archpresbyter Peter, and the priest and abbot Peter of S. Sabas, and to let them return uninjured with the joyful intelligence that the Emperors were persevering in the orthodox faith, as they had begun.”

The Pope undoubtedly, at the same time, addressed his (undated) letter to the Patriarch Tarasius, which was read at the second session at Nicæa in a Greek translation. Anastasius says that the Greeks had also omitted much in this document, but that the original text was in the Roman archives. Yet in this case the Latin agrees with the Greek in all the principal points, for the latter also contains the fault-finding, that Tarasius, being a layman, had immediately become patriarch, and a strong assertor of the Roman primacy. Indeed, the papal letter begins with fault-finding on that account. As, on the one hand, he was troubled by this uncanonical promotion, so, on the other side, was the Pope rejoiced by the assurance of the orthodoxy of Tarasius. Without this he could not have accepted his Synodica. He praises him, and exhorts him to persevere, and remarks that he had with pleasure resolved to send legates to the contemplated Synod. But Tarasius must take measures that the false assembly against the images, which had been held in an irregular manner without the apostolic see, should be anathematised in the presence of the papal representatives, so that all the tares should be rooted out, and the word of Christ should be fulfilled, who had left the primacy to the Roman Church. If Tarasius would adhere to this see, he must take care that the Emperors should have the images restored in the capital city and everywhere; for if this was not done, he could not recognise his consecration. Finally, he should give a friendly reception to the papal legates.

It was probably a little later that an answer to the Synodica of Tarasius arrived from the three Oriental patriarchates. Evidently this did not come from those patriarchs themselves, but from Oriental monks, because, as the latter openly assert, the messengers of Tarasius could not reach the patriarchs on account of the enmity of the Arabs. The contents are as follows: “When the letter of Tarasius, inspired by God, arrived, we, the last among the inhabitants of the wilderness (i.e. the monks in the deserts), were seized with horror and joy at the same time: with horror, from fear of those impious ones whom we were forced to serve for our sins; but with joy, because in that letter the truth of the orthodox faith shines like the rays of the sun. A light from on high, as Zacharias says (S. Luke 1:78), has visited us, to lighten us who sit in the shadow of death (that is, Arabian impiety), and to guide our feet into the way of peace. It has raised for us a horn of salvation, which you (Tarasius) are, and the God-loving rulers who occupy the second place in the Church. A wise and holy Emperor said: The greatest gift which God has bestowed upon men is the Saccrdotium and the Imperium. The former orders and guides the heavenly, the latter governs the earthly with righteous laws. Now, happily, the Sacerdotium and the Imperium are united, and we, who were a reproach to our neighbours (on account of the ecclesiastical division between the East and Byzantium), may again joyfully look up to heaven.

“The messengers whom you sent to the Oriental patriarchs, under God’s guidance met with our brethren (other monks), disclosed to them the aim of their mission, and were by them concealed, out of fear of the enemies of the Cross. But those monks did not trust in their own discernment, but rather sought counsel, and came to us without the knowledge of those whom they had concealed. After we had sworn to them to observe silence, they imparted the matter to us; and we prayed God for enlightenment, and then declared to them: As we know the enmity of the rejected nation (the Saracens), those envoys should be kept back, and not allowed to travel to the patriarchs; on the contrary, they should be brought to us and earnestly exhorted to make no noise, as this would bring ruin on the now peaceable churches and the subject Christian peoples. Those envoys, however, after receiving our explanation, were indignant with us. They said they had been sent to give up their lives for the Church, and perfectly to fulfil the commission of the patriarch and the Emperors. We replied to them, that there was here no question merely as to their lives only, but as to the existence of the whole Church in the East; and when they hesitated to return with their commissions not executed, we besought our brothers John and Thomas, the syncelli of the two great patriarchs (of Alexandria and Antioch), to travel with your envoys to Constantinople, to undertake their defence, and to deliver by word of mouth that which would require too much detail in writing. As the patriarch of the see of S. James (Jerusalem) had been exiled, on account of a trivial accusation, to a distance of 2000 stones (so that no special vicar could be appointed for him), John and Thomas were appointed to bear testimony to the apostolic tradition of Egypt and Syria in Constantinople, and to do what was required of them there. (The messengers of Tarasius had already explained the aim of the Synod which was to be held, and therefore a commission might be given to the two monks referred to, which through its indefiniteness might be offensive.) They excused themselves from defect of learning, but followed our wish, and departed with your envoys. Receive them kindly, and present them to the Emperors. They know the tradition of the three apostolic sees, who receive six Œcumenical Synods, but utterly reject the so-called seventh, summoned for the destruction of images. If, however, you celebrate a Synod, you must not be restrained from holding it by the absence of the three patriarchs and the bishops subject to them, for they are not voluntarily wanting, but in consequence of the threats and injuries of the Saracens. In the same way, they were absent from the sixth Synod for the same reason; and yet this in no way diminished the importance of that Council, particularly as the Pope of Rome gave his assent, and was present by his deputy. For the confirmation of our letter, and in order to convince you perfectly (of the orthodoxy of the East), we present the Synodica which the Patriarch Theodore of Jerusalem of blessed memory sent to Cosmas of Alexandria and Theodore of Antioch, and in return for which he received, during his lifetime, Synodicæ from them.”

This Synodica of the departed patriarch of Jerusalem was probably intended to supply the lack of a special deputy from this diocese. It begins with a very lengthy orthodox confession of faith, then recognises the six Œcumenical Synods, and regards any other as superfluous, as those six had completely exhausted the tradition of the Fathers, and nothing was to be added or could improve it. After several anathemas on the heretics, from their head, Simon Magus, down to the tail, the veneration of the saints (τιμᾶν καὶ προσκυνεῖν τοὺς ἁγίους καὶ ἀσπάζεσθαι) is declared to be an apostolic tradition, a healing power is ascribed to their relics, and an inference is drawn from the Incarnation of Christ, justifying the representation of Him in images and the veneration of those images. There is added to this a defence of the images of Mary and the apostles, etc., by reference to the cherubim which Moses caused to be made.

SEC. 346. The First Attempt at the holding of an Œcumenical Synod miscarries

After the Roman and Oriental envoys had arrived in Constantinople, the rulers summoned also the bishops of their kingdom. As, however, the Synod could not be opened at once on account of the absence of the Court in Thrace, this was made use of by the still considerable number of enemies of the images among the bishops, in union with many laymen, to hinder the meeting of the Synod and to maintain the prohibition of the Synod. At the same time, they intrigued against the Patriarch Tarasius, and held several assemblies. But he forbade this on canonical grounds, under penalty of deposition, whereupon they withdrew.

Soon afterwards the rulers returned from Thrace, and fixed the 17th of August for the opening of the Synod, in the Church of the Apostles at Constantinople. On the previous day many military men assembled in the λουτὴρ (either baptistry or porch, in which the font, λουτὴρ, stood) of the Church of the Apostles, and protested with great noise and tumult against the holding of the new Synod. Nevertheless it was opened on the following day. The Patriarch Tarasius assumed the presidency, and the rulers looked on from the place of the catechumens. The passages of Holy Scripture referring to the images were considered, and the arguments for and against the veneration of images examined. The Abbot Plato particularly distinguished himself by delivering from the ambo a discourse in defence of the images, at the request of Tarasius. Naturally, the new Synod decided to declare the earlier one of the year 754 invalid, and to this end caused the older canons to be read, according to which an Œcumenical Synod could not be held without the participation of the other patriarchs. But in agreement with the few bishops who were hostile to the images, and incited by their officers, the soldiers of the imperial bodyguard, posted before the church doors, who had served under Copronymus, pushed with a great noise into the interior of the church, marched with naked weapons up to the bishops, and threatened to kill them all, along with the patriarch and the monks. The Emperors immediately sent some high Court officials to rebuke them and bid them be at peace, but they answered with insults, and refused obedience. Upon this, Tarasius withdrew with the bishops from the nave of the church into the sanctuary (which with the Greeks, as is well known, is shut off by a wall), and the rulers declared the Synod dissolved. The enemies of the images among the bishops then cried out joyfully, “We have conquered,” and with their friends commended the so-called seventh Synod. Many bishops now departed, among them the papal legates.

SEC. 347. Convocation of the Synod of Nicæa

When the legates arrived in Sicily, they were called back to Constantinople, for Irene had not given up the project of a Synod, and had got rid of her mutinous bodyguard by a stratagem. She pretended an expedition against the Arabs, and the whole Court removed, in September 786, with the bodyguard, to Malagina in Thrace. Other troops, under trustworthy leaders, had therefore to be brought into Constantinople; another bodyguard was formed, those insubordinate ones were disarmed and sent back to their native provinces. After this was done, Irene sent messengers through the whole Empire, in May 787, to summon the bishops to a new Synod at Nicæa in Bithynia. That the Pope gave his assent to this is clear from what has been said, from his letters to the Court and to Tarasius, and from the sending of his legates. Moreover, he afterwards said expressly in his letter to Charles the Great: Et sic synodum istam secundum nostram ordinationem fecerunt.

The reasons for choosing Nicæa are evident. Constantinople itself necessarily seemed unsuitable after what had happened the year before, and because, perhaps, many enemies of the images lived there. Nicæa, on the other hand, was not very far removed from the capital city, so that a connection between the Synod and the Court could be effected without much difficulty, and had, besides, the memory of the first most highly esteemed Œcumenical Council, under Constantine the Great, in its favour; and moreover, the fourth Œcumenical Synod (of Chalcedon) was first summoned to Nicæa, and was only removed to Chalcedon because of intervening circumstances (see vol. iii. pp. 278 and 283). Moreover, similar circumstances brought it about, in the case of the present Synod, that the eighth and last session was celebrated on October 23, 787, in the imperial palace at Constantinople. The Empress and her son were not personally present at the sessions of Nicæa, but were represented by two high officers of State, the patricius and ex-consul Petronus, and the imperial ostiarius (chamberlain) and logothetes (chancellor of the military chancery) John. Nicephorus, subsequently patriarch, was appointed secretary. Among the spiritual members, the two Roman legates, the Archpresbyter Peter and the Abbot Peter (p. 353) are regularly placed first in the Acts, and first after them the Patriarch Tarasius of Constantinople, and then the two Oriental monks and priests John and Thomas, as representatives of the patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. From the transactions themselves, we learn that Tarasius essentially conducted the business, as also the Sicilian bishops nominated him, at the first session, τὸν προκαθεζόμενον.

The question has often been brought up, with what right did those two monks, John and Thomas, act at Nicæa as representatives of the Oriental patriarchs, since, as we saw, information of the summoning of the Synod had never been brought to those patriarchs? Here was undeniable deception and falsehood. But the letter of the Oriental monks, which gives the whole history of the matter in a thoroughly unadorned and circumstantial manner, was read at the second session of Nicæa, so that not one person could believe that John and Thomas had been sent directly by the Oriental patriarchs. The ἀρχιερεῖς, by whom they were deputed, and who are named in the superscription, as we remarked above (p. 354), were not patriarchs, but monk-priests of higher rank, who acted sedibus impeditis instead of the inaccessible patriarchs. The necessity of the case would justify this. John and Thomas, however, subscribed at Nicæa not as vicars of the patriarchs (quâ persons), but of the apostolic sees (θρόνοι = churches) of the East, and they might properly be so designated materially, for, in union with the two letters which they brought with them, they represented, in fact, the faith of the three Oriental patriarchates in regard to the images and the veneration of them. Apart from them and the Roman legates, all present were subjects of the Byzantine kingdom. The number of the members, partly bishops, partly representatives of bishops, is given by the ancients as between 330 and 367; and when the almost contemporaneous patriarch Nicephorus speaks only of 150, this is evidently incorrect, since the still extant minutes of the Synod give not fewer than 308 bishops and representatives of bishops as subscribers of the decrees of Nicæa. Besides, as the Acts here and there indicate, there were also present a good many monks and clerics not entitled to vote. The Patriarch Tarasius also speaks of archimandrites and hegumeni and a πληθὺς μοναχῶν. Several imperial secretaries and clerics of Constantinople also acted as officials of the Synod.

SEC. 348. The First Session of Nicæa

After the bishops had arrived in Nicæa, during the summer of 787, the first session was held there, September 24, 787, in the Church of S. Sophia. As was usual, here also the books of the holy Gospels were solemnly placed upon a throne. In front of the ambo sat the two imperial commissaries and the archimandrites etc., who had no right to vote. At the wish of the Sicilian bishops, the Patriarch Tarasius opened the transactions with a short speech, as follows: “At the beginning of. August in the previous year, it had been wished to hold a Synod under his presidency, in the Church of the Apostles at Constantinople; but through the fault of some bishops, who could easily be numbered, but whom he would not name, as every one knew them, they had been hindered by force. The gracious rulers had therefore summoned a new Synod to Nicæa, and Christ would reward them for this. This Helper the bishops should also invoke, and in all uprightness, without discursiveness, deliver a righteous judgment.” This warning against discursiveness was very much in place because of the loquacity of the Greeks, but it does not seem to have profited much, for the Acts of our Synod are full of examples of unnecessary logomachy.

After Tarasius had ended his speech, three bishops,—Basil of Ancyra, Theodore of Myra, and Theodosius of Amorium,—who had hitherto been enemies of the images, were introduced and placed before the Synod. Before they were permitted to answer for themselves, another imperial Sacra was read, the publication of which, as we know (p. 352), had been required by Pope Hadrian. It contained, in accordance with ancient usage, the assurance that every member of the Synod was allowed to speak quite freely and without hindrance, according to his conviction; then gives information of the resignation of the Patriarch Paul and of the election of Tarasius, together with the desire of both for reunion with the rest of the Church, and after the holding of an Œcumenical Synod; and mentions, finally, the letters of the Pope and of the Oriental archpriests, which were soon to be read aloud in the Synod.

Upon this, the three bishops who had hitherto been hostile to the images begged forgiveness, and read a formula of faith and recantation, whereupon they were received into fellowship, and assigned their place in the Synod. Seven other bishops then entered, who, a year before, had contributed to frustrate the intended Synod, and had held separate assemblies—namely, Hypatius of Nicæa, Leo of Rhodes, Gregory of Pessinus, Leo of Iconium, George of Pisidia, Nicolas of Hierapolis, and Leo of the island of Carpathus. They had erred, they said, only from ignorance, and were ready to confess and confirm the faith handed down from the apostles and Fathers. The Synod was doubtful whether they should be admitted to communion, and therefore they had many older ecclesiastical maxims read, particularly canons of the apostles and of different Councils, also judgments of the Fathers of the Church, respecting the receiving back of heretics. On this occasion, John, one of the vicars of the Oriental patriarchates, declared that the veneration of images was the worst of all heresies, “because it detracted from the Economy (Incarnation) of the Redeemer.” Tarasius, however, drew from the passages read the conclusion, that the seven bishops should be received, if no other fault attached to them. Many members of the Synod called out together: “We have all erred; we all pray for forgiveness.” The question was then proposed, whether those who had obtained ordination from heretics should be received again; but before the books necessary for this subject arrived, they proceeded with the presentation of proofs of the first kind on the reception of heretics generally. Finally the wished-for books arrived, and they read from the Church histories of Rufinus, Socrates, and Theodore the lector, from the Acts of Chalcedon, from the Vita S. Sabæ, etc., proofs that, in earlier times, those who had been ordained by heretics had been received again. The actual admission of the seven bishops, however, was deferred until a later session.

SEC. 349. The Second Session

When the second session began, September 26, at the command of the Court an imperial official presented to the Synod Bishop Gregory of Neo-Cæsarea, who had also formerly been hostile to the images, but now wished to return to orthodoxy. Tarasius, however, treated him with some harshness, and seemed to doubt his sincerity. But when Gregory gave the best assurances and lamented his former errors, he was required to appear again at the next session and to present a written statement. After this the letter of Pope Hadrian, of October 27, 785, to the Emperors, already known to us, was read aloud (p. 349), although not in its entirety; and the Roman legates, at the request of Tarasius, testified that they had received this letter from the hand of the apostolic Father himself. This testimony was confirmed by Bishop Theodore of Catanea and deacon Epiphanius, who had conveyed the imperial Jussio to Rome, and had been present at the delivery of the papal answer (see p. 349).

In the same way, the letter of Hadrian to Tarasius was read, and at the request of the Roman legates the latter declared that he was in agreement with the doctrine contained in the letter, and accepted the veneration of the images. “We reverence them,” he says, “with relative regard (ταύτας σχετικῷ πόθῳ προσκυνοῦμεν), since they are made in the name of Christ and of His inviolate Mother, of the holy angels and all saints: Our λατρεία and πίστις, however, we evidently dedicate to God alone.” When all exclaimed: “Thus believes the whole Synod,” the Roman legates demanded a special vote on the recognition of the two papal letters which had been read, and this followed in 263 votes, partly representative and partly personal, of the bishops and representatives of bishops (with exception of the legates themselves and Tarasius, who had declared himself already). Finally, Tarasius asked the monks present to give their assent individually, which was then done. Thus ended the second session.

SEC. 350. The Third Session

In the third session, according to the Greek Acts on the 28th, according to Anastasius on the 29th, of September, Gregory of Neo-Cæsarea handed in and read the declaration of faith in writing which had been required of him. It was nothing else but a repetition of that which Basil of Ancyra and his colleagues had presented at the first session. Before, however, Gregory was received into favour, Tarasius remarked that he had heard that some bishops in earlier times (under Copronymus) had persecuted and ill-treated some pious venerators of images. He would not believe this without proof (probably he had Bishop Gregory in such suspicion), but he must remark that the apostolic canons punished such an offence with deposition. Several members of the Synod agreed with him, and it was resolved that, if anyone should bring forward such complaints, he was to present himself immediately to Tarasius or the Synod. As, however, Gregory of Neo-Cæsarea gave the assurance that in this respect he was quite blameless, the Synod declared itself ready to receive him, although several monks intimated that he had been one of the heads of the false Council of the year 754. Mildness prevailed, and along with Gregory, at the same time, the bishops of Rhodes, Iconium, Hierapolis, Pessinus, and Carpathus were received, and assigned to their seats.

The Synodica addressed by Tarasius to the patriarchs of the East was then read (see p. 346), together with the answer of the Oriental ἀρχιερεῖς and the Synodica of the departed patriarch, Theodore of Jerusalem (see p. 354); and the Roman legates declared, with the concurrence of the whole assembly, that these Oriental letters were completely in harmony with the doctrine of Pope Hadrian and of the Patriarch Tarasius. The words employed at this voting by Bishop Constantine of Constantia, free from deception as they were, gave occasion, subsequently, at Cyprus, to the most violent reproaches against the Nicene Synod. He said: “I assent to these declarations now read, I receive and greet with all reverence the sacred images; the προσκύνησις κατὰ λατρείαν, i.e. the adoration, I offer to the Holy Trinity alone.” By false translation and misunderstanding the Frankish bishops subsequently, at the Synod of Frankfort, A.D. 794, and also in the Carolingian books (iii. 17), understood this to mean that a demand had been made at Nicæa that the same devotion should be offered to the images as to the Most Holy Trinity.

SEC. 351. The Fourth Session

The fourth session, on October 1, was intended to prove the legitimacy of the veneration of images from the Holy Scriptures and the Fathers. On the proposal of Tarasius, there was read by the secretaries and officials of the Synod a great series of biblical and patristic passages bearing on this subject, which partly had been collected beforehand and partly were now presented by individual members of the Synod. The biblical passages were:

(1) Exodus 25:17–22, and Numbers 7:88, 89, in regard to the ark of the covenant, the mercy-seat, and the cherubims which were over it.

(2) Ezekiel 41:1, 18, 19, on the cherubim with faces, and the palms, etc., which Ezekiel beheld in the new temple of God.

(3) Hebrews 9:1–5, where Paul speaks of the tabernacle, and of the objects contained in it: the golden pot with the manna, Aaron’s rod, the tables of the law, and the cherubim.

Tarasius then remarked: “Even the Old Testament had its divine symbols, the cherubim; and from this they went on to the New Testament. And if the Old Testament had cherubim which overshadowed the mercy-seat, we might also have images of Christ and of the saints to overshadow our mercy-seat.” Further, he pointed out, as did Bishop Constantine of Constantia, in Cyprus, that even the cherubim of the Old Testament had a human countenance; and the angels, as often as they appeared to men, according to the testimony of Holy Scripture, appeared in human form. Moses, indeed, had so formed the cherubim (Ex. 25.), as they were shown to him in the mount. The prohibition of images had first been published by God when the Israelites showed themselves inclined to idolatry. John, one of the vicars from the East, remarked that God Himself had appeared to Jacob in human form, and had wrestled with him (Gen. 32:24).

The series of patristic proofs is opened by a passage from the panegyric of Chrysostom on Meletius, in which it is said that the faithful had made representations of this saint upon their rings, cups, shells, on the walls and everywhere. A second passage from another discourse of Chrysostom alludes to the picture of an angel who drove out the barbarians. There was also read from Gregory of Nyssa, how, at the sight of a picture of the offering of Isaac, he had been forced to weep; and Bishop Basil of Ancyra at this justly remarked, that this father had often read this history in the Bible without weeping, whilst the representation of it in a picture had moved him to tears. “If this happened to a learned man,” added the monk John, “how much more must it be useful to the unlearned, that they may be touched!” “Yes,” exclaimed Bishop Theodore of Catanea; “and how much more must men be touched by a picture of the sufferings of Christ!” Representations of the offering of Isaac are treated in a passage of S. Cyril of Alexandria; a poem of Gregory of Nazianzus speaks of a picture of S. Polemon, by looking at which an immodest woman was converted; a discourse of Antipater of Bostra refers to the statue which the woman who was healed by Christ of the issue of blood caused to be erected. A great fragment of Bishop Asterius of Amasia gives a full description of a picture representing the martyrdom of S. Euphemia. Next came two passages from the martyrdom and the miracles of the Persian martyr Anastasius (†627), which speak of the custom of setting up images in the churches, as well as testify to the veneration of relics, and moreover, of the divine punishment which smote a despiser of relics at Cæsarea. A pretended discourse of Athanasius describes the miracle at Berytus, where the Jews pierced a picture of Christ with a lance, on which blood and water ran out. They collected this, and, as all the sick who were touched with this became well, the whole city received the Christian faith.

A passage was read from the letter of S. Nilus to Heliodore, relating that the holy martyr Plato had appeared to a young monk in a vision just as he had seen him in pictures; upon which Bishop Theodore of Myra remarked that the same had happened to his pious archdeacon in regard to S. Nicolas. As, however, the enemies of the images also appealed to Nilus, the passage used by them from his letter to Olympiodorus was also read. Nilus certainly in this letter blames some kinds of images in churches and monasteries, namely, representations of hares, goats, beasts of every kind, from hunting and fishing, and recommends instead the simple figure of the cross; but he also commends the historical representations, from the Old and New Testaments, on the walls of the churches for the instruction of the unlearned; and this very clause was omitted by the enemies of the images when they brought forward the passage (A.D. 754), as several bishops now maintained. Another passage from the transactions between the Abbot Maximus and the Monothelite deputies sent to him, Theodorius of Cæsarea, etc. (see p. 131), showed that both the latter and also that learned abbot had reverenced the Gospels and the images of Christ, and the Oriental deputy John remarked that the images must be necessary, or they would not have been venerated by those men.

Naturally, an appeal was made to the eighty-two Trullan canons on the images. They were ascribed to the sixth Œcumenical Synod, whilst Tarasius maintained that the same Fathers who constituted this Synod had again assembled, four or five years later (i.e. 685 or 686), and had drawn up canons. That this was a mistake we have already shown (p. 221). As, however, they shared in this mistake at Rome (see p. 241), we can understand why the papal legates did not protest against the identification of the Quinisexta with the sixth Œcumenical Synod.

After the reading of a series of further patristic proofs in favour of the veneration of images, among them the letters, already mentioned, of Pope Gregory II. and of the Patriarch Germanus of Constantinople to John of Synnada, etc., and after anathemas had been pronounced upon the enemies of images, Euthymius of Sardes presented the synodal Decree of the Faith. The Synod there calls itself holy and œcumenical, again assembled at Nicæa by the will of God and at the command of the two rulers, the new Helena and the new Constantine, then declares its agreement with the six previous Œcumenical Synods, then adds a short Symbolum, and passes on to its special theme with the words: “Christ has delivered us from idolatry by His incarnation, His death, and His resurrection.” It goes on: “It is not a Synod, it is not an Emperor, as the Jewish sanhedrim (the false Synod of A.D. 754) maintained, which has freed us from the error of idolatry; but it is Christ the Lord Himself who has done this. To Him, therefore, belongs the glory and honour, and not to men. We are taught by the Lord, the apostles, and the prophets, that we ought to honour and praise before all the holy God-bearer, who is exalted above all heavenly powers; further, the holy angels, the apostles, prophets, and martyrs, the holy doctors, and all saints, that we may avail ourselves of their intercession, which can make us acceptable to God if we walk virtuously. Moreover, we venerate also the image of the sacred and life-giving cross and the relics of the saints, and accept the sacred and venerable images, and greet and embrace them, according to the ancient tradition of the holy catholic Church of God, namely, of our holy Fathers, who received these images, and ordered them to be set up in all churches everywhere. These are the representations of our Incarnate Saviour Jesus Christ, then of our inviolate Lady and quite holy God-bearer, and of the unembodied angels, who have appeared to the righteous in human form; also the pictures of the holy apostles, prophets, martyrs, etc., that we may be reminded by the representation of the original, and may be led to a certain participation in his holiness.”

This decree was subscribed by all present, even the priors of monasteries and some monks. The two papal legates added to their subscription the remark, that they received all who had been converted from the impious heresy of the enemies of images.

SEC. 352. The Fifth Session

On the opening of the fifth session, October 4, Tarasius remarked that the accusers of the Christians (see p. 358) had, in their destruction of images, imitated the Jews, Saracens, Samaritans, Manichæans, and Phantasiasti or Theopaschites. Further patristic passages were then read, and even those which seemed to speak against the veneration of images. (1) The series was opened by a passage from the second Catechesis of Cyril of Jerusalem, which blames the removal of the cherubim from the Jewish temple by Nebuchadnezzar. (2) A letter from Simeon Stylites the younger († 592) to the Emperor Justin II., asks him to punish the Samaritans because they had dishonoured the holy images. (3) Two dialogues, between a heathen and a Christian, and between a Jew and a Christian, defend the images. (4) Two passages from the pseudo-epigraphic book περίοδοι τῶν ἁγίων ἀποστόλων speak against the images, and were used by the iconoclasts at their Synod, A.D. 754, because therein John the Evangelist blames a disciple who, from attachment to him, had caused his portrait to be painted. The Synod attributed no value to these passages, because they had been taken from an apocryphal and heretical book. (5) As the enemies of images appealed to a letter from the Church historian Eusebius to Constantia, the consort of Licinius, in which her wish to possess a portrait of Christ is blamed, the Synod now shows the heterodoxy of Eusebius from his own utterances, and from one of Antipater of Bostra. In the same way (6) Xenaias and Severus, who rejected the images, were represented as heretics (Monophysites, see vol. iii. pp. 456, 459). (7) Among the proofs in favour of the images, the writings of the deacon and chartophylax Constantine of Constantinople were adduced; and it was remarked that the enemies of the images had burned many manuscripts, in the patriarchal archives at Constantinople and elsewhere, which spoke against them, and also had torn out some leaves from a writing of Constantine in which the images are discussed. On the other hand, they had left the silver boards with which the book was bound, and these boards were adorned with pictures of saints. A passage was then read from the writing of that Constantine on the martyrs, in which he shows how the martyrs had, in opposition to the heathen, shown the difference between the Christian veneration of images and idolatry, and had based the former upon the incarnation of Christ. Probably this was the passage which had been torn out in the copy at Constantinople. In the same way, it was found, with several other manuscripts adduced, that leaves had been cut out of them. As the originators of these outrages, they designated the former patriarchs, Anastasius, Constantine, and Nicetas of Constantinople.

The presentation and reading of fifteen further passages from the Fathers, which were in readiness, the Synod held to be unnecessary, as the ancient tradition of the Church in regard to the images was clear from what had been read. On the other side, the monk John, representative of the East, asked leave to clear up the real origin of the attack on the images, and related that story of the Caliph Jezid and the Jews which we have given above (p. 268). It was then decreed by the Synod that the images should everywhere be restored, and at them prayers should be offered. In the same way, they approved the proposal of the papal legates, that henceforth, and indeed on the next day, a sacred image should be set up in their own locality, and that the writings composed against the images should be burnt. The session closed with acclamations and anathemas against the enemies of images, and with praises of the Emperors.

SEC. 353. The Sixth Session

The sixth session was held, according to the Greek text of the Acts on the 6th, according to the translation of Anastasius on the 5th, of October, and immediately on its being opened, the Secretary Leontius informed them that there lay to-day before them the ὅρος (decree) of the false Council of A.D. 754, as well as an excellent refutation of it. The Synod ordered the reading of both, and Bishop Gregory of Neo-Cæsarea was required to read the words of the ὅρος, and the deacons John and Epiphanius of Constantinople to read the much more comprehensive document in opposition to it. The composer we do not know. It is divided (with the ὅρος, which is included in it) into six tomi, and in Mansi comprehends no less than 160 folio pages, and in Hardouin, 120. The principal contents of the ὅρος have already been given in connection with the account of the iconoclastic false Synod of the year 754 (see p. 307). The other document opposes the ὅρος from sentence to sentence, and in this way contains much that is certainly superfluous, and is of unnecessary extent. But it contains also many excellent and acute observations, which thoroughly deserve the commendation which Leontius gave to the whole. The assumptions of that false Synod are therein powerfully met, and its sophistries exposed (e.g., that no picture of Christ could be painted without falling into heresy). That the originators of the ὅρος were often harshly treated, is not to be wondered at, and, considering the dishonesty with which they went to work, perfectly justifiable. In proof that the use of images went back to apostolic times, the refutation appeals (tom. iv.) to the statue of Christ which the woman healed by Him of the issue of blood had caused to be set up in gratitude (see p. 367), and to the universal tradition of the Fathers; and then shows fully that the iconoclasts were mistaken in appealing to certain passages of Holy Scripture and of the Fathers (tom. v.). It was then shown, particularly, that the patristic passages quoted by them were partly quite spurious, partly garbled by them, distorted, and falsely interpreted. If they brought forward the letter of Eusebius to Constantine (see p. 371), this was without importance, because the writer had been malæ famæ in reference to his orthodoxy. In conclusion, in tom. vi., the particular sentence of the false Synod, together with its anathematisms, is subjected to a criticism which is often pungent.

SEC. 354. The Seventh Session

Of special importance was the seventh session, on October 13, when the ὅρος (decree) of our Synod was read by Bishop Theodore of Taurianum. Who was the author of it is unknown; but we may naturally think of Tarasius, and at the same time assume that the solemn publication of this decree was preceded by a careful exhortation and discussion from the same hand, although the minutes are silent on the subject. The Synod declares in this ὅρος that they intended to take nothing away from the ecclesiastical tradition, and to add nothing to it, but to preserve all that was catholic unaltered, and follow the six Œcumenical Councils. The Synod then repeats the symbol of Nicæa and that of Constantinople without filioque; pronounces anathema on Arius, Macedonius, and their adherents; then, with the Synod of Ephesus, confesses that Mary is truly the God-bearer; believes, with the Synod of Chalcedon, in two natures in Christ; anathematises, with the fifth Council, the false doctrines of Origen, Evagrius, and Didymus (there is no word of the Three Chapters); with the sixth Synod, which had condemned Sergius, Honorius, etc., preaches two wills in Christ, and professes faithfully to preserve all written and unwritten traditions, among them also the tradition in respect to the images. It concludes, therefore, “that as the figure of the sacred cross, so also sacred figures—whether of colour or of stone or of any other material—may be depicted on vessels, on clothes and walls, on tables, in houses and on roads, namely, the figures of Jesus Christ, of our immaculate Lady, of the venerable angels, and of all holy men. The oftener one looked on these representations, the more would the looker be stirred to the remembrance of the originals, and to the imitation of them, and to offer his greeting and his reverence to them (ἀσπασμὸν καὶ τιμητικὴν προσκύνησιν), not the actual λατρεία (τὴν ἀληθινὴν λατρείαν) which belonged to the Godhead alone, but that he should offer, as to the figure of the sacred cross, as to the holy Gospels (books), and to other sacred things, incense and lights in their honour, as this had been a sacred custom with the ancients; for the honour which is shown to the figure passes over to the original, and whoever does reverence (προσκυνεῖ) to an image does reverence to the person represented by it.

“Whoever shall teach otherwise, and reject that which is dedicated to the Church, whether it be the book of the Gospels, or the figure of the cross or any other figure, or the relics of a martyr, or whoever shall imagine anything for the destruction of the tradition of the Catholic Church, or shall turn the sacred vessels or the venerable monasteries to a profane use, if he is a bishop or cleric, shall be deposed; if a monk or layman, excommunicated.” This decree was subscribed by those present, and all exclaimed: “Thus we believe: this is the doctrine of the apostles. Anathema to all who do not adhere to it, who do not greet the images, who call them idols, and for this reason reproach the Christians with idolatry. Many years to the Emperor! eternal remembrance to the new Constantine and the new Helena! God preserve their government! Anathema to all heretics! Anathema in particular to Theodosius, the false bishop of Ephesus (p. 267), and in like manner to Sisinnius, surnamed Pastillas, and to Basil with the evil surname of Tricaccabus! The Holy Trinity has rejected their doctrines. Anathema to Anastasius, Constantine, and Nicetas, who, one after the other, occupied the throne of Constantinople! They are: Arius II., Nestorius II., and Dioscurus II. Anathema to John of Nicomedia and Constantine of Nacolia, those heresiarchs! If anyone defends a member of the heresy which slanders the Christians, let him be anathema! If anyone does not confess that Christ, in His manhood, has a circumscribed form, let him be anathema! If anyone does not allow the explanation of the Gospels by figures, let him be anathema! If anyone does not greet these things which are made in the name of the Lord and the saints, let him be anathema! If anyone rejects the tradition of the Church, written or unwritten, let him be anathema! Eternal remembrance to Germanus (of Constantinople), to John (of Damascus), and to George (of Cyprus, see p. 314), these heralds of the truth!

At the same time, a letter addressed by Tarasius and the Synod to the rulers, Constantine and Irene, reported what had taken place, explained the expression προσκυνεῖν, that the Bible and the Fathers employed this word to signify the reverence accorded to men, whilst λατρεία was reserved for God alone. A deputation of bishops, hegumeni, and clerics was also appointed, to present to the rulers a selection from the patristic passages in proof used by the Synod.

A second letter was addressed by the Synod to the priests and clerics of the principal and other churches of Constantinople, in order to make them acquainted with the decrees which had been drawn up.

SEC. 355. The Eighth Session

The rulers then gave orders, in a decree addressed to Tarasius, that he, along with the rest of the bishops, etc., should now come to Constantinople. This took place. The Empress received them in the most friendly manner, and decided that, on the 23rd of October, a new session, the eighth and last, should be held in the presence of the two rulers, in the palace Magnaura. After Tarasius, by command of the Emperor, had opened this session with a suitable discourse, the two rulers themselves made a friendly address to the Synod, amid the liveliest acclamations from the members, ordered the ὅρος which had been drawn up at the previous session to be read again, and made the proposal, “that the holy and Œcumenical Synod should declare whether this ὅρος had been accepted with universal assent.” All the members exclaimed: “Thus we believe, thus think we all: we have all agreed and subscribed. This is the faith of the apostles, the faith of the Fathers, the faith of the orthodox.… Anathema to those who do not adhere to this faith!” etc. (almost the very same words as after the reading of the ὅρος at the seventh session; see p. 374 f.).

At the prayer of the Synod, the two rulers now also subscribed the ὅρος, Irene first, and for this they were again greeted with the most friendly acclamations. At the close the rulers caused to be read again the patristic testimonies in favour of the veneration of images, from Chrysostom and others, which had been used at the fourth session; and, after this was done, all the bishops and the uncommonly numerous multitude of people and military present stood up, and expressed with acclamations the universal assent, and gave thanks to God for what had been done. Finally, the bishops were allowed to return to their homes, with rich presents from the Emperor.

SEC. 356. The Canons of the Seventh Œcumenical Synod

Among the Acts of our Synod there are 22 canons, which Anastasius places in the preface to his translation of the seventh Council, but which the later collection of Councils assigned to the eighth. The latter followed the tenor of the 10th canon, in which Constantinople (not Nicæa) is mentioned as the place at which it was held; but even the apparent contradiction of Anastasius is removed, when we consider that he considers the solemn closing transaction at Constantinople as one actio with the seventh and last session at Nicæa. In the same manner, most among the ancients, Greeks and Latins, generally reckoned only seven sessions. The principal contents of these canons are as follows:—

1. “The clergy must observe the holy canons, and we recognise as such those of the apostles and of the six Œcumenical Councils; further, those which have been sent from particular Synods for publication (ἔκδοσις) at the other Synods, and also the canons of our holy Fathers. Whomsoever these canons anathematise, we also anathematise; whom they depose, we also depose; whom they expel, we also expel; whom they punish, we visit with the same punishment.”

Like the Greeks generally, so our Synod also recognised not merely, like the West, fifty, but eighty-five so-called apostolic canons (see vol. i. ad fin.). Moreover, they speak of the canons of the first six Œcumenical Councils, whilst it is well known that the fifth and sixth Œcumenical Synods published no canons. But also here our Synod acts in accordance with the custom of the Greeks, in regarding the 102 canons of the Quinisext as Œcumenical, and especially in ascribing them to the sixth Œcumenical Synod. With regard to this, Anastasius remarked, in the preface to his Latin translation of the synodal Acts, that the Council brought forward canons of the apostles and of the six Œcumenical Synods which Rome did not recognise, but the present Pope (John VIII.) had made an excellent distinction among them. We have already given this above, at p. 240.

2. “If anyone wishes to be ordained bishop, he must know the psalter perfectly (by heart), that he may therefrom suitably exhort the clergy who are subject to him; and the metropolitan must make inquiry as to whether he has striven to read also the sacred canons, the Holy Gospel, further, the Apostolos (the apostolic epistles), and the whole of the sacred Scriptures, not merely cursorily, but also thoroughly, and whether he walks according to the divine commands, and so teaches the people. For the essence (οὐσία) of our hierarchy are the divinely-delivered maxims, namely, the true understanding of the sacred Scriptures, as the great Dionysius (the Areopagite) says.”

This canon is, in the translation of Anastasius, taken into the Corpus jur. can. c. 6, Dist. xxxviii.

3. “Every election of a bishop, priest, or deacon, proceeding from a secular prince, is invalid, in accordance with the ancient rule (Can. Apostol. n. 31), and a bishop must only be elected by bishops, according to can. 4 of Nicæa.”

That by this the right of patronage belonging to secular rulers, and the many indults granted to Kings to designate bishops, are not taken away or forbidden, but that the opinion that the granting of ecclesiastical positions belongs to princes jure DOMINATIONIS is condemned, is shown by Van Espen, l.c. p. 460. In the Corpus jur. can. our canon occurs as c. 7, Dist. lxiii.

4. “No bishop may demand money or the like from other bishops or clerics, or from the monks subject to him. If, however, a bishop deprives one of the clergy subject to him of his office, or shuts up his church from covetousness or from any passion, so that divine service can no longer be held in it, he shall himself be liable to the same fate (deposition), and the evil which he wished to hold over another shall fall back upon his own head.” In the Corpus jur. can. c. 64, Causa xvi. q. 1.

5. “Those who boast of having obtained a position in the Church by the expenditure of money, and who depreciate others who have been chosen because of their virtuous life and by the Holy Ghost without money, these shall, in the first place, be put back to the lowest grade of their order, and if then also they still persist (in their pride), they shall be punished by the bishop. But if anyone has given money in order to obtain ordination, the 30th apostolic canon and the 2nd canon of Chalcedon apply to him (vol. i. p. 469; vol. iii. p. 386). He and his ordainer are to be deposed and excommunicated.”

Zonaras and Balsamon in earlier times, and later, Christian Lupus and Van Espen, remarked that the second part of our canon treated of simony, but not the first. This has in view rather those who, on account of their large expenditure on churches and the poor, have been raised (without simony) to the clerical state as a reward and recognition of their beneficence; and, being proud of this, now depreciate other clergy who were unable or unwilling to make such foundations and the like.

6. “According to canon 8 of the sixth Œcumenical Council (i.e. the Quinisext), a provincial Synod should be held every year. A prince who hinders this is excommunicated, a metropolitan who is negligent in it is subject to the canonical punishments. The bishops assembled should take care that the life-giving commands of God are followed. The metropolitan, however, must demand nothing from the bishops. If he does so, he is to be punished fourfold.”

Anastasius remarks on this, that this ordinance (whether the whole canon or only its last passage must remain undecided) was not accepted by the Latins. That this canon did not forbid the so-called Synodicum, which the metropolitans had lawfully to receive from the bishops, and the bishops from the priests, is remarked by Van Espen, l.c. p. 464. Gratian received our canon at c. 7, Dist. xviii.

7. “As every sin has again other sins as its consequence, so the heresies of the slanderers of Christians (iconoclasts) drew other impieties after them. They not merely took away the sacred images, but also abandoned other ecclesiastical customs, which must now be renewed. We therefore ordain that, in all temples which were consecrated without having relics, these must be placed with the customary prayers. If, in future, a bishop consecrates a church without relics, he shall be deposed.”

8. “Jews who have become Christians only in appearance, and who continue secretly to observe the Sabbath and other Jewish usages, must be admitted neither to communion nor to prayer, nor may even be allowed to visit the churches. Their children are not to be baptized, and they may not purchase or possess any (Christian) slave. If, however, a Jew sincerely repents, he is to be received and baptized, and in like manner his children.”

The Greek commentators Balsamon and Zonaras understood the words μήτε τοὺς παῖδας αὐτῶν βαπτίζειν to mean, “these seeming Christians may not baptize their own children,” because they only seem to be Christians. But parents were never allowed to baptize their own children, and the true sense of the words in question comes out clearly from the second half of the canon.

9. “All writings against the venerable images are to be delivered up into the episcopal residence at Constantinople, and then put aside (shut up) along with the other heretical books. If anyone conceals them, he must, if bishop, priest, or deacon, be deposed; if monk or layman, anathematised.”

10. “As some clerics, despising the canonical ordinance, leave their parish (= diocese) and pass over into other dioceses, particularly betake themselves to powerful lords in this metropolitan city preserved by God, and perform divine service in their oratories (εὐκτηρίοις), henceforth no one shall receive them into his house or his church without the previous knowledge of their own bishop and the bishop of Constantinople. If anyone does so, and persists in it, he shall be deposed. But those who do so with the previous knowledge of those bishops (i.e. become domestic chaplains with persons of distinction), may not at the same time undertake secular business (of these lords), since the canons forbid this. If, however, one has undertaken the business of the so-called Majores (μειζοτεροί, majores domus, stewards of the estates of high personages), he must lay this down or be deposed. He ought rather to instruct the children and the servants, and read the Holy Scriptures to them, for to this end he has received the sacred ordination.”

On the office of the μειζότεροι, the Greek commentators Zonaras and Balsamon (l.c. p. 301) give us more exact information. We have given the substance of it in the parenthesis.

11. “In accordance with the ancient ordinance (c. 26 of Chalcedon, see vol. iii. p. 409), an œconomus should be appointed in every church. If a metropolitan does not attend to this, then the patriarch of Constantinople is to appoint an œconomus for his church. Metropolitans have the same right in regard to their bishops. This prescription applies to monasteries.”

The Synod of Chalcedon required the appointment of special œconomi only for all bishops’ churches; but our Synod extended this prescription also to monasteries. Gratian received this canon as c. 3, Causa ix. q. 3.

12. “If a bishop or abbot gives away anything from the property of the bishopric or the monastery to a prince or anyone else, this is invalid according to the 39th apostolic canon; even if it is done under the pretext that the property in question is of no value. In such a case the property is to be given away, not to secular lords, but to clerics or colonists. If, however, after this has been done, the secular lord buys the property in question of the cleric or colonist, and thus goes cunningly to work, then such a purchase is invalid; and if a bishop or abbot used such cunning (i.e. got rid of church property in such a roundabout way), he must be deposed.” In Corpus jur. Canon. our canon is c. 19, Causa xii. q. 2.