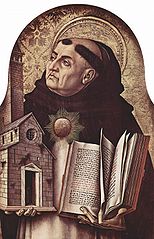

The Summa Theologica by Saint Thomas Aquinas

OF THE WILL (FIVE ARTICLES)

We next consider the will. Under this head there are five points of inquiry:

(1) Whether the will desires something of necessity?

(2) Whether it desires anything of necessity?

(3) Whether it is a higher power than the intellect?

(4) Whether the will moves the intellect?

(5) Whether the will is divided into irascible and concupiscible?

Whether the will desires something of necessity?

Objection 1: It would seem that the will desires nothing. For Augustine says (De Civ. Dei v, 10) that it anything is necessary, it is not voluntary. But whatever the will desires is voluntary. Therefore nothing that the will desires is desired of necessity.

Objection 2: Further, the rational powers, according to the Philosopher (Metaph. viii, 2), extend to opposite things. But the will is a rational power, because, as he says (De Anima iii, 9), “the will is in the reason.” Therefore the will extends to opposite things, and therefore it is determined to nothing of necessity.

Objection 3: Further, by the will we are masters of our own actions. But we are not masters of that which is of necessity. Therefore the act of the will cannot be necessitated.

On the contrary, Augustine says (De Trin. xiii, 4) that “all desire happiness with one will.” Now if this were not necessary, but contingent, there would at least be a few exceptions. Therefore the will desires something of necessity.

I answer that, The word “necessity” is employed in many ways. For that which must be is necessary. Now that a thing must be may belong to it by an intrinsic principle—either material, as when we say that everything composed of contraries is of necessity corruptible—or formal, as when we say that it is necessary for the three angles of a triangle to be equal to two right angles. And this is “natural” and “absolute necessity.” In another way, that a thing must be, belongs to it by reason of something extrinsic, which is either the end or the agent. On the part of the end, as when without it the end is not to be attained or so well attained: for instance, food is said to be necessary for life, and a horse is necessary for a journey. This is called “necessity of end,” and sometimes also “utility.” On the part of the agent, a thing must be, when someone is forced by some agent, so that he is not able to do the contrary. This is called “necessity of coercion.”

Now this necessity of coercion is altogether repugnant to the will. For we call that violent which is against the inclination of a thing. But the very movement of the will is an inclination to something. Therefore, as a thing is called natural because it is according to the inclination of nature, so a thing is called voluntary because it is according to the inclination of the will. Therefore, just as it is impossible for a thing to be at the same time violent and natural, so it is impossible for a thing to be absolutely coerced or violent, and voluntary.

But necessity of end is not repugnant to the will, when the end cannot be attained except in one way: thus from the will to cross the sea, arises in the will the necessity to wish for a ship.

In like manner neither is natural necessity repugnant to the will. Indeed, more than this, for as the intellect of necessity adheres to the first principles, the will must of necessity adhere to the last end, which is happiness: since the end is in practical matters what the principle is in speculative matters. For what befits a thing naturally and immovably must be the root and principle of all else appertaining thereto, since the nature of a thing is the first in everything, and every movement arises from something immovable.

Reply to Objection 1: The words of Augustine are to be understood of the necessity of coercion. But natural necessity “does not take away the liberty of the will,” as he says himself (De Civ. Dei v, 10).

Reply to Objection 2: The will, so far as it desires a thing naturally, corresponds rather to the intellect as regards natural principles than to the reason, which extends to opposite things. Wherefore in this respect it is rather an intellectual than a rational power.

Reply to Objection 3: We are masters of our own actions by reason of our being able to choose this or that. But choice regards not the end, but “the means to the end,” as the Philosopher says (Ethic. iii, 9). Wherefore the desire of the ultimate end does not regard those actions of which we are masters.

Whether the will desires of necessity, whatever it desires?

Objection 1: It would seem that the will desires all things of necessity, whatever it desires. For Dionysius says (Div. Nom. iv) that “evil is outside the scope of the will.” Therefore the will tends of necessity to the good which is proposed to it.

Objection 2: Further, the object of the will is compared to the will as the mover to the thing movable. But the movement of the movable necessarily follows the mover. Therefore it seems that the will’s object moves it of necessity.

Objection 3: Further, as the thing apprehended by sense is the object of the sensitive appetite, so the thing apprehended by the intellect is the object of the intellectual appetite, which is called the will. But what is apprehended by the sense moves the sensitive appetite of necessity: for Augustine says (Gen. ad lit. ix, 14) that “animals are moved by things seen.” Therefore it seems that whatever is apprehended by the intellect moves the will of necessity.

On the contrary, Augustine says (Retract. i, 9) that “it is the will by which we sin and live well,” and so the will extends to opposite things. Therefore it does not desire of necessity all things whatsoever it desires.

I answer that, The will does not desire of necessity whatsoever it desires. In order to make this evident we must observe that as the intellect naturally and of necessity adheres to the first principles, so the will adheres to the last end, as we have said already [658](A[1]). Now there are some things intelligible which have not a necessary connection with the first principles; such as contingent propositions, the denial of which does not involve a denial of the first principles. And to such the intellect does not assent of necessity. But there are some propositions which have a necessary connection with the first principles: such as demonstrable conclusions, a denial of which involves a denial of the first principles. And to these the intellect assents of necessity, when once it is aware of the necessary connection of these conclusions with the principles; but it does not assent of necessity until through the demonstration it recognizes the necessity of such connection. It is the same with the will. For there are certain individual goods which have not a necessary connection with happiness, because without them a man can be happy: and to such the will does not adhere of necessity. But there are some things which have a necessary connection with happiness, by means of which things man adheres to God, in Whom alone true happiness consists. Nevertheless, until through the certitude of the Divine Vision the necessity of such connection be shown, the will does not adhere to God of necessity, nor to those things which are of God. But the will of the man who sees God in His essence of necessity adheres to God, just as now we desire of necessity to be happy. It is therefore clear that the will does not desire of necessity whatever it desires.

Reply to Objection 1: The will can tend to nothing except under the aspect of good. But because good is of many kinds, for this reason the will is not of necessity determined to one.

Reply to Objection 2: The mover, then, of necessity causes movement in the thing movable, when the power of the mover exceeds the thing movable, so that its entire capacity is subject to the mover. But as the capacity of the will regards the universal and perfect good, its capacity is not subjected to any individual good. And therefore it is not of necessity moved by it.

Reply to Objection 3: The sensitive power does not compare different things with each other, as reason does: but it simply apprehends some one thing. Therefore, according to that one thing, it moves the sensitive appetite in a determinate way. But the reason is a power that compares several things together: therefore from several things the intellectual appetite—that is, the will—may be moved; but not of necessity from one thing.

Whether the will is a higher power than the intellect?

Objection 1: It would seem that the will is a higher power than the intellect. For the object of the will is good and the end. But the end is the first and highest cause. Therefore the will is the first and highest power.

Objection 2: Further, in the order of natural things we observe a progress from imperfect things to perfect. And this also appears in the powers of the soul: for sense precedes the intellect, which is more noble. Now the act of the will, in the natural order, follows the act of the intellect. Therefore the will is a more noble and perfect power than the intellect.

Objection 3: Further, habits are proportioned to their powers, as perfections to what they make perfect. But the habit which perfects the will—namely, charity—is more noble than the habits which perfect the intellect: for it is written (1 Cor. 13:2): “If I should know all mysteries, and if I should have all faith, and have not charity, I am nothing.” Therefore the will is a higher power than the intellect.

On the contrary, The Philosopher holds the intellect to be the higher power than the will.

I answer that, The superiority of one thing over another can be considered in two ways: “absolutely” and “relatively.” Now a thing is considered to be such absolutely which is considered such in itself: but relatively as it is such with regard to something else. If therefore the intellect and will be considered with regard to themselves, then the intellect is the higher power. And this is clear if we compare their respective objects to one another. For the object of the intellect is more simple and more absolute than the object of the will; since the object of the intellect is the very idea of appetible good; and the appetible good, the idea of which is in the intellect, is the object of the will. Now the more simple and the more abstract a thing is, the nobler and higher it is in itself; and therefore the object of the intellect is higher than the object of the will. Therefore, since the proper nature of a power is in its order to its object, it follows that the intellect in itself and absolutely is higher and nobler than the will. But relatively and by comparison with something else, we find that the will is sometimes higher than the intellect, from the fact that the object of the will occurs in something higher than that in which occurs the object of the intellect. Thus, for instance, I might say that hearing is relatively nobler than sight, inasmuch as something in which there is sound is nobler than something in which there is color, though color is nobler and simpler than sound. For as we have said above ([659]Q[16], A[1]; [660]Q[27], A[4]), the action of the intellect consists in this—that the idea of the thing understood is in the one who understands; while the act of the will consists in this—that the will is inclined to the thing itself as existing in itself. And therefore the Philosopher says in Metaph. vi (Did. v, 2) that “good and evil,” which are objects of the will, “are in things,” but “truth and error,” which are objects of the intellect, “are in the mind.” When, therefore, the thing in which there is good is nobler than the soul itself, in which is the idea understood; by comparison with such a thing, the will is higher than the intellect. But when the thing which is good is less noble than the soul, then even in comparison with that thing the intellect is higher than the will. Wherefore the love of God is better than the knowledge of God; but, on the contrary, the knowledge of corporeal things is better than the love thereof. Absolutely, however, the intellect is nobler than the will.

Reply to Objection 1: The aspect of causality is perceived by comparing one thing to another, and in such a comparison the idea of good is found to be nobler: but truth signifies something more absolute, and extends to the idea of good itself: wherefore even good is something true. But, again, truth is something good: forasmuch as the intellect is a thing, and truth its end. And among other ends this is the most excellent: as also is the intellect among the other powers.

Reply to Objection 2: What precedes in order of generation and time is less perfect: for in one and in the same thing potentiality precedes act, and imperfection precedes perfection. But what precedes absolutely and in the order of nature is more perfect: for thus act precedes potentiality. And in this way the intellect precedes the will, as the motive power precedes the thing movable, and as the active precedes the passive; for good which is understood moves the will.

Reply to Objection 3: This reason is verified of the will as compared with what is above the soul. For charity is the virtue by which we love God.

Whether the will moves the intellect?

Objection 1: It would seem that the will does not move the intellect. For what moves excels and precedes what is moved, because what moves is an agent, and “the agent is nobler than the patient,” as Augustine says (Gen. ad lit. xii, 16), and the Philosopher (De Anima iii, 5). But the intellect excels and precedes the will, as we have said above [661](A[3]). Therefore the will does not move the intellect.

Objection 2: Further, what moves is not moved by what is moved, except perhaps accidentally. But the intellect moves the will, because the good apprehended by the intellect moves without being moved; whereas the appetite moves and is moved. Therefore the intellect is not moved by the will.

Objection 3: Further, we can will nothing but what we understand. If, therefore, in order to understand, the will moves by willing to understand, that act of the will must be preceded by another act of the intellect, and this act of the intellect by another act of the will, and so on indefinitely, which is impossible. Therefore the will does not move the intellect.

On the contrary, Damascene says (De Fide Orth. ii, 26): “It is in our power to learn an art or not, as we list.” But a thing is in our power by the will, and we learn art by the intellect. Therefore the will moves the intellect.

I answer that, A thing is said to move in two ways: First, as an end; for instance, when we say that the end moves the agent. In this way the intellect moves the will, because the good understood is the object of the will, and moves it as an end. Secondly, a thing is said to move as an agent, as what alters moves what is altered, and what impels moves what is impelled. In this way the will moves the intellect and all the powers of the soul, as Anselm says (Eadmer, De Similitudinibus). The reason is, because wherever we have order among a number of active powers, that power which regards the universal end moves the powers which regard particular ends. And we may observe this both in nature and in things politic. For the heaven, which aims at the universal preservation of things subject to generation and corruption, moves all inferior bodies, each of which aims at the preservation of its own species or of the individual. The king also, who aims at the common good of the whole kingdom, by his rule moves all the governors of cities, each of whom rules over his own particular city. Now the object of the will is good and the end in general, and each power is directed to some suitable good proper to it, as sight is directed to the perception of color, and the intellect to the knowledge of truth. Therefore the will as agent moves all the powers of the soul to their respective acts, except the natural powers of the vegetative part, which are not subject to our will.

Reply to Objection 1: The intellect may be considered in two ways: as apprehensive of universal being and truth, and as a thing and a particular power having a determinate act. In like manner also the will may be considered in two ways: according to the common nature of its object—that is to say, as appetitive of universal good—and as a determinate power of the soul having a determinate act. If, therefore, the intellect and the will be compared with one another according to the universality of their respective objects, then, as we have said above [662](A[3]), the intellect is simply higher and nobler than the will. If, however, we take the intellect as regards the common nature of its object and the will as a determinate power, then again the intellect is higher and nobler than the will, because under the notion of being and truth is contained both the will itself, and its act, and its object. Wherefore the intellect understands the will, and its act, and its object, just as it understands other species of things, as stone or wood, which are contained in the common notion of being and truth. But if we consider the will as regards the common nature of its object, which is good, and the intellect as a thing and a special power; then the intellect itself, and its act, and its object, which is truth, each of which is some species of good, are contained under the common notion of good. And in this way the will is higher than the intellect, and can move it. From this we can easily understand why these powers include one another in their acts, because the intellect understands that the will wills, and the will wills the intellect to understand. In the same way good is contained in truth, inasmuch as it is an understood truth, and truth in good, inasmuch as it is a desired good.

Reply to Objection 2: The intellect moves the will in one sense, and the will moves the intellect in another, as we have said above.

Reply to Objection 3: There is no need to go on indefinitely, but we must stop at the intellect as preceding all the rest. For every movement of the will must be preceded by apprehension, whereas every apprehension is not preceded by an act of the will; but the principle of counselling and understanding is an intellectual principle higher than our intellect—namely, God—as also Aristotle says (Eth. Eudemic. vii, 14), and in this way he explains that there is no need to proceed indefinitely.

Whether we should distinguish irascible and concupiscible parts in the superior appetite?

Objection 1: It would seem that we ought to distinguish irascible and concupiscible parts in the superior appetite, which is the will. For the concupiscible power is so called from “concupiscere” [to desire], and the irascible part from “irasci” [to be angry]. But there is a concupiscence which cannot belong to the sensitive appetite, but only to the intellectual, which is the will; as the concupiscence of wisdom, of which it is said (Wis. 6:21): “The concupiscence of wisdom bringeth to the eternal kingdom.” There is also a certain anger which cannot belong to the sensitive appetite, but only to the intellectual; as when our anger is directed against vice. Wherefore Jerome commenting on Mat. 13:33 warns us “to have the hatred of vice in the irascible part.” Therefore we should distinguish irascible and concupiscible parts of the intellectual soul as well as in the sensitive.

Objection 2: Further, as is commonly said, charity is in the concupiscible, and hope in the irascible part. But they cannot be in the sensitive appetite, because their objects are not sensible, but intellectual. Therefore we must assign an irascible and concupiscible power to the intellectual part.

Objection 3: Further, it is said (De Spiritu et Anima) that “the soul has these powers”—namely, the irascible, concupiscible, and rational—“before it is united to the body.” But no power of the sensitive part belongs to the soul alone, but to the soul and body united, as we have said above (Q[78], AA[5],8). Therefore the irascible and concupiscible powers are in the will, which is the intellectual appetite.

On the contrary, Gregory of Nyssa (Nemesius, De Nat. Hom.) says “that the irrational” part of the soul is divided into the desiderative and irascible, and Damascene says the same (De Fide Orth. ii, 12). And the Philosopher says (De Anima iii, 9) “that the will is in reason, while in the irrational part of the soul are concupiscence and anger,” or “desire and animus.”

I answer that, The irascible and concupiscible are not parts of the intellectual appetite, which is called the will. Because, as was said above ([663]Q[59], A[4]; [664]Q[79], A[7]), a power which is directed to an object according to some common notion is not differentiated by special differences which are contained under that common notion. For instance, because sight regards the visible thing under the common notion of something colored, the visual power is not multiplied according to the different kinds of color: but if there were a power regarding white as white, and not as something colored, it would be distinct from a power regarding black as black.

Now the sensitive appetite does not consider the common notion of good, because neither do the senses apprehend the universal. And therefore the parts of the sensitive appetite are differentiated by the different notions of particular good: for the concupiscible regards as proper to it the notion of good, as something pleasant to the senses and suitable to nature: whereas the irascible regards the notion of good as something that wards off and repels what is hurtful. But the will regards good according to the common notion of good, and therefore in the will, which is the intellectual appetite, there is no differentiation of appetitive powers, so that there be in the intellectual appetite an irascible power distinct from a concupiscible power: just as neither on the part of the intellect are the apprehensive powers multiplied, although they are on the part of the senses.

Reply to Objection 1: Love, concupiscence, and the like can be understood in two ways. Sometimes they are taken as passions—arising, that is, with a certain commotion of the soul. And thus they are commonly understood, and in this sense they are only in the sensitive appetite. They may, however, be taken in another way, as far as they are simple affections without passion or commotion of the soul, and thus they are acts of the will. And in this sense, too, they are attributed to the angels and to God. But if taken in this sense, they do not belong to different powers, but only to one power, which is called the will.

Reply to Objection 2: The will itself may be said to irascible, as far as it wills to repel evil, not from any sudden movement of a passion, but from a judgment of the reason. And in the same way the will may be said to be concupiscible on account of its desire for good. And thus in the irascible and concupiscible are charity and hope—that is, in the will as ordered to such acts. And in this way, too, we may understand the words quoted (De Spiritu et Anima); that the irascible and concupiscible powers are in the soul before it is united to the body (as long as we understand priority of nature, and not of time), although there is no need to have faith in what that book says. Whence the answer to the third objection is clear.

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running