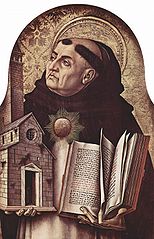

The Summa Theologica by Saint Thomas Aquinas

OF THE RELATIONS OF THE SAINTS TOWARDS THE DAMNED (THREE ARTICLES)

We must next consider the relations of the saints towards the damned. Under this head there are three points of inquiry:

(1) Whether the saints see the sufferings of the damned?

(2) Whether they pity them?

(3) Whether they rejoice in their sufferings?

Whether the blessed in heaven will see the sufferings of the damned?

Objection 1: It would seem that the blessed in heaven will not see the sufferings of the damned. For the damned are more cut off from the blessed than wayfarers. But the blessed do not see the deeds of wayfarers: wherefore a gloss on Is. 63:16, “Abraham hath not known us,” says: “The dead, even the saints, know not what the living, even their own children, are doing” [*St. Augustine, De cura pro mortuis xiii, xv]. Much less therefore do they see the sufferings of the damned.

Objection 2: Further, perfection of vision depends on the perfection of the visible object: wherefore the Philosopher says (Ethic. x, 4) that “the most perfect operation of the sense of sight is when the sense is most disposed with reference to the most beautiful of the objects which fall under the sight.” Therefore, on the other hand, any deformity in the visible object redounds to the imperfection of the sight. But there will be no imperfection in the blessed. Therefore they will not see the sufferings of the damned wherein there is extreme deformity.

On the contrary, It is written (Is. 66:24): “They shall go out and see the carcasses of the men that have transgressed against Me”; and a gloss says: “The elect will go out by understanding or seeing manifestly, so that they may be urged the more to praise God.”

I answer that, Nothing should be denied the blessed that belongs to the perfection of their beatitude. Now everything is known the more for being compared with its contrary, because when contraries are placed beside one another they become more conspicuous. Wherefore in order that the happiness of the saints may be more delightful to them and that they may render more copious thanks to God for it, they are allowed to see perfectly the sufferings of the damned.

Reply to Objection 1: This gloss speaks of what the departed saints are able to do by nature: for it is not necessary that they should know by natural knowledge all that happens to the living. But the saints in heaven know distinctly all that happens both to wayfarers and to the damned. Hence Gregory says (Moral. xii) that Job’s words (14:21), “‘Whether his children come to honour or dishonour, he shall not understand,’ do not apply to the souls of the saints, because since they possess the glory of God within them, we cannot believe that external things are unknown to them.” [*Concerning this Reply, Cf. [5136]FP, Q[89], A[8]].

Reply to Objection 2: Although the beauty of the thing seen conduces to the perfection of vision, there may be deformity of the thing seen without imperfection of vision: because the images of things whereby the soul knows contraries are not themselves contrary. Wherefore also God Who has most perfect knowledge sees all things, beautiful and deformed.

Whether the blessed pity the unhappiness of the damned?

Objection 1: It would seem that the blessed pity the unhappiness of the damned. For pity proceeds from charity [*Cf. SS, Q[30]]; and charity will be most perfect in the blessed. Therefore they will most especially pity the sufferings of the damned.

Objection 2: Further, the blessed will never be so far from taking pity as God is. Yet in a sense God compassionates our afflictions, wherefore He is said to be merciful.

On the contrary, Whoever pities another shares somewhat in his unhappiness. But the blessed cannot share in any unhappiness. Therefore they do not pity the afflictions of the damned.

I answer that, Mercy or compassion may be in a person in two ways: first by way of passion, secondly by way of choice. In the blessed there will be no passion in the lower powers except as a result of the reason’s choice. Hence compassion or mercy will not be in them, except by the choice of reason. Now mercy or compassion comes of the reason’s choice when a person wishes another’s evil to be dispelled: wherefore in those things which, in accordance with reason, we do not wish to be dispelled, we have no such compassion. But so long as sinners are in this world they are in such a state that without prejudice to the Divine justice they can be taken away from a state of unhappiness and sin to a state of happiness. Consequently it is possible to have compassion on them both by the choice of the will—in which sense God, the angels and the blessed are said to pity them by desiring their salvation—and by passion, in which way they are pitied by the good men who are in the state of wayfarers. But in the future state it will be impossible for them to be taken away from their unhappiness: and consequently it will not be possible to pity their sufferings according to right reason. Therefore the blessed in glory will have no pity on the damned.

Reply to Objection 1: Charity is the principle of pity when it is possible for us out of charity to wish the cessation of a person’s unhappiness. But the saints cannot desire this for the damned, since it would be contrary to Divine justice. Consequently the argument does not prove.

Reply to Objection 2: God is said to be merciful, in so far as He succors those whom it is befitting to be released from their afflictions in accordance with the order of wisdom and justice: not as though He pitied the damned except perhaps in punishing them less than they deserve.

Whether the blessed rejoice in the punishment of the wicked?

Objection 1: It would seem that the blessed do not rejoice in the punishment of the wicked. For rejoicing in another’s evil pertains to hatred. But there will be no hatred in the blessed. Therefore they will not rejoice in the unhappiness of the damned.

Objection 2: Further, the blessed in heaven will be in the highest degree conformed to God. Now God does not rejoice in our afflictions. Therefore neither will the blessed rejoice in the afflictions of the damned.

Objection 3: Further, that which is blameworthy in a wayfarer has no place whatever in a comprehensor. Now it is most reprehensible in a wayfarer to take pleasure in the pains of others, and most praiseworthy to grieve for them. Therefore the blessed nowise rejoice in the punishment of the damned.

On the contrary, It is written (Ps. 57:11): “The just shall rejoice when he shall see the revenge.”

Further, it is written (Is. 56:24): “They shall satiate [*Douay: ‘They shall be a loathsome sight to all flesh.’] the sight of all flesh.” Now satiety denotes refreshment of the mind. Therefore the blessed will rejoice in the punishment of the wicked.

I answer that, A thing may be a matter of rejoicing in two ways. First directly, when one rejoices in a thing as such: and thus the saints will not rejoice in the punishment of the wicked. Secondly, indirectly, by reason namely of something annexed to it: and in this way the saints will rejoice in the punishment of the wicked, by considering therein the order of Divine justice and their own deliverance, which will fill them with joy. And thus the Divine justice and their own deliverance will be the direct cause of the joy of the blessed: while the punishment of the damned will cause it indirectly.

Reply to Objection 1: To rejoice in another’s evil as such belongs to hatred, but not to rejoice in another’s evil by reason of something annexed to it. Thus a person sometimes rejoices in his own evil as when we rejoice in our own afflictions, as helping us to merit life: “My brethren, count it all joy when you shall fall into divers temptations” (James 1:2).

Reply to Objection 2: Although God rejoices not in punishments as such, He rejoices in them as being ordered by His justice.

Reply to Objection 3: It is not praiseworthy in a wayfarer to rejoice in another’s afflictions as such: yet it is praiseworthy if he rejoice in them as having something annexed. However it is not the same with a wayfarer as with a comprehensor, because in a wayfarer the passions often forestall the judgment of reason, and yet sometimes such passions are praiseworthy, as indicating the good disposition of the mind, as in the case of shame pity and repentance for evil: whereas in a comprehensor there can be no passion but such as follows the judgment of reason.

OF THE GIFTS* OF THE BLESSED (FIVE ARTICLES) [*The Latin ‘dos’ signifies a dowry.]

We must now consider the gifts of the blessed; under which head there are five points of inquiry:

(1) Whether any gifts should be assigned to the blessed?

(2) Whether a gift differs from beatitude?

(3) Whether it is fitting for Christ to have gifts?

(4) Whether this is competent to the angels?

(5) Whether three gifts of the soul are rightly assigned?

Whether any gifts should be assigned as dowry to the blessed?

Objection 1: It would seem that no gifts should be assigned as dowry to the blessed. For a dowry (Cod. v, 12, De jure dot. 20: Dig. xxiii, 3, De jure dot.) is given to the bridegroom for the upkeep of the burdens of marriage. But the saints resemble not the bridegroom but the bride, as being members of the Church. Therefore they receive no dowry.

Objection 2: Further, the dowry is given not by the bridegroom’s father, but by the father of the bride (Cod. v, 11, De dot. promiss., 1: Dig. xxiii, 2, De rit. nup.). Now all the beatific gifts are bestowed on the blessed by the father of the bridegroom, i.e. Christ: “Every best gift and every perfect gift is from above coming down from the Father of lights.” Therefore these gifts which are bestowed on the blessed should not be called a dowry.

Objection 3: Further, in carnal marriage a dowry is given that the burdens of marriage may be the more easily borne. But in spiritual marriage there are no burdens, especially in the state of the Church triumphant. Therefore no dowry should be assigned to that state.

Objection 4: Further, a dowry is not given save on the occasion of marriage. But a spiritual marriage is contracted with Christ by faith in the state of the Church militant. Therefore if a dowry is befitting the blessed, for the same reason it will be befitting the saints who are wayfarers. But it is not befitting the latter: and therefore neither is it befitting the blessed.

Objection 5: Further, a dowry pertains to external goods, which are styled goods of fortune: whereas the reward of the blessed will consist of internal goods. Therefore they should not be called a dowry.

On the contrary, It is written (Eph. 5:32): “This is a great sacrament: but I speak in Christ and in the Church.” Hence it follows that the spiritual marriage is signified by the carnal marriage. But in a carnal marriage the dowered bride is brought to the dwelling of the bridegroom. Therefore since the saints are brought to Christ’s dwelling when they are beatified, it would seem that they are dowered with certain gifts.

Further, a dowry is appointed to carnal marriage for the ease of marriage. But the spiritual marriage is more blissful than the carnal marriage. Therefore a dowry should be especially assigned thereto.

Further, the adornment of the bride is part of the dowry. Now the saints are adorned when they are taken into glory, according to Is. 61:10, “He hath clothed me with the garments of salvation . . . as a bride adorned with her jewels.” Therefore the saints in heaven have a dowry.

I answer that, Without doubt the blessed when they are brought into glory are dowered by God with certain gifts for their adornment, and this adornment is called their dowry by the masters. Hence the dower of which we speak now is defined thus: “The dowry is the everlasting adornment of soul and body adequate to life, lasting for ever in eternal bliss.” This description is taken from a likeness to the material dowry whereby the bride is adorned and the husband provided with an adequate support for his wife and children, and yet the dowry remains inalienable from the bride, so that if the marriage union be severed it reverts to her. As to the reason of the name there are various opinions. For some say that the name “dowry” is taken not from a likeness to the corporeal marriage, but according to the manner of speaking whereby any perfection or adornment of any person whatever is called an endowment; thus a man who is proficient in knowledge is said to be endowed with knowledge, and in this sense ovid employed the word “endowment” (De Arte Amandi i, 538): “By whatever endowment thou canst please, strive to please.” But this does not seem quite fitting, for whenever a term is employed to signify a certain thing principally, it is not usually transferred to another save by reason of some likeness. Wherefore since by its primary signification a dowry refers to carnal marriage, it follows that in every other application of the term we must observe some kind of likeness to its principal signification. Consequently others say that the likeness consists in the fact that in carnal marriage a dowry is properly a gift bestowed by the bridegroom on the bride for her adornment when she is taken to the bridegroom’s dwelling: and that this is shown by the words of Sichem to Jacob and his sons (Gn. 34:12): “Raise the dowry, and ask gifts,” and from Ex. 22:16: “If a man seduce a virgin . . . and lie with her, he shall endow her, and have her to wife.” Hence the adornment bestowed by Christ on the saints, when they are brought into the abode of glory, is called a dowry. But this is clearly contrary to what jurists say, to whom it belongs to treat of these matters. For they say that a dowry, properly speaking, is a donation on the part of the wife made to those who are on the part of the husband, in view of the marriage burden which the husband has to bear; while that which the bridegroom gives the bride is called “a donation in view of marriage.” In this sense dowry is taken (3 Kings 9:16) where it is stated that “Pharoa, the king of Egypt, took Gezer . . . and gave it for a dowry to his daughter, Solomon’s wife.” Nor do the authorities quoted prove anything to the contrary. For although it is customary for a dowry to be given by the maiden’s parents, it happens sometimes that the bridegroom or his father gives the dowry instead of the bride’s father; and this happens in two ways: either by reason of his very great love for the bride as in the case of Sichem’s father Hemor, who on account of his son’s great love for the maiden wished to give the dowry which he had a right to receive; or as a punishment on the bridegroom, that he should out of his own possessions give a dowry to the virgin seduced by him, whereas he should have received it from the girl’s father. In this sense Moses speaks in the passage quoted above. Wherefore in the opinion of others we should hold that in carnal marriage a dowry, properly speaking, is that which is given by those on the wife’s side to those on the husband’s side, for the bearing of the marriage burden, as stated above. Yet the difficulty remains how this signification can be adapted to the case in point, since the heavenly adornments are given to the spiritual spouse by the Father of the Bridegroom. This shall be made clear by replying to the objections.

Reply to Objection 1: Although in carnal marriage the dowry is given to the bridegroom for his use, yet the ownership and control belong to the bride: which is evident by the fact that if the marriage be dissolved, the dowry reverts to the bride according to law (Cap. 1,2,3, De donat. inter virum et uxorem). Thus also in spiritual marriage, the very adornments bestowed on the spiritual bride, namely the Church in her members, belong indeed to the Bridegroom, in so far as they conduce to His glory and honor, yet to the bride as adorned thereby.

Reply to Objection 2: The Father of the Bridegroom, that is of Christ, is the Person of the Father alone: while the Father of the bride is the whole Trinity, since that which is effected in creatures belongs to the whole Trinity. Hence in spiritual marriage these endowments, properly speaking, are given by the Father of the bride rather than by the Father of the Bridegroom. Nevertheless, although this endowment is made by all the Persons, it may be in a manner appropriated to each Person. To the Person of the Father, as endowing, since He possesses authority; and fatherhood in relation to creatures is also appropriated to Him, so that He is Father of both Bridegroom and bride. To the Son it is appropriated, inasmuch as it is made for His sake and through Him: and to the Holy Ghost, inasmuch as it is made in Him and according to Him, since love is the reason of all giving [*Cf. [5137]FP, Q[38], A[2]].

Reply to Objection 3: That which is effected by the dowry belongs to the dowry by its nature, and that is the ease of marriage: while that which the dowry removes, namely the marriage burden which is lightened thereby, belongs to it accidentally: thus it belongs to grace by its nature to make a man righteous, but accidentally to make an ungodly man righteous. Accordingly, though there are no burdens in the spiritual marriage, there is the greatest gladness; and that this gladness may be perfected the bride is dowered with gifts, so that by their means she may be happily united with the bridegroom.

Reply to Objection 4: The dowry is usually settled on the bride not when she is espoused, but when she is taken to the bridegroom’s dwelling, so as to be in the presence of the bridegroom, since “while we are in the body we are absent from the Lord” (2 Cor. 5:6). Hence the gifts bestowed on the saints in this life are not called a dowry, but those which are bestowed on them when they are received into glory, where the Bridegroom delights them with His presence.

Reply to Objection 5: In spiritual marriage inward comeliness is required, wherefore it is written (Ps. 44:14): “All the glory of the king’s daughter is within,” etc. But in carnal marriage outward comeliness is necessary. Hence there is no need for a dowry of this kind to be appointed in spiritual marriage as in carnal marriage.

Whether the dowry is the same as beatitude*? [*Cf. FP, Q[12], A[7], ad 1; FS, Q[4], A[3]]

Objection 1: It would seem that the dowry is the same as beatitude. For as appears from the definition of dowry [5138](A[1]), the dowry is “the everlasting adornment of body and soul in eternal happiness.” Now the happiness of the soul is an adornment thereof. Therefore beatitude is a dowry.

Objection 2: Further, a dowry signifies something whereby the union of bride and bridegroom is rendered delightful. Now such is beatitude in the spiritual marriage. Therefore beatitude is a dowry.

Objection 3: Further, according to Augustine (In Ps. 92) vision is “the whole essence of beatitude.” Now vision is accounted one of the dowries. Therefore beatitude is a dowry.

Objection 4: Further, fruition gives happiness. Now fruition is a dowry. Therefore a dowry gives happiness and thus beatitude is a dowry.

Objection 5: Further, according to Boethius (De Consol. iii), “beatitude is a state made perfect by the aggregate of all good things.” Now the state of the blessed is perfected by the dowries. Therefore the dowries are part of beatitude.

On the contrary, The dowries are given without merits: whereas beatitude is not given, but is awarded in return for merits. Therefore beatitude is not a dowry.

Further, beatitude is one only, whereas the dowries are several. Therefore beatitude is not a dowry.

Further, beatitude is in man according to that which is principal in him (Ethic. x, 7): whereas a dowry is also appointed to the body. Therefore dowry and beatitude are not the same.

I answer that, There are two opinions on this question. For some say that beatitude and dowry are the same in reality but differ in aspect: because dowry regards the spiritual marriage between Christ and the soul, whereas beatitude does not. But seemingly this will not stand, since beatitude consists in an operation, whereas a dowry is not an operation, but a quality or disposition. Wherefore according to others it must be stated that beatitude and dowry differ even in reality, beatitude being the perfect operation itself by which the soul is united to God, while the dowries are habits or dispositions or any other qualities directed to this same perfect operation, so that they are directed to beatitude instead of being in it as parts thereof.

Reply to Objection 1: Beatitude, properly speaking, is not an adornment of the soul, but something resulting from the soul’s adornment; since it is an operation, while its adornment is a certain comeliness of the blessed themselves.

Reply to Objection 2: Beatitude is not directed to the union but is the union itself of the soul with Christ. This union is by an operation, whereas the dowries are gifts disposing to this same union.

Reply to Objection 3: Vision may be taken in two ways. First, actually, i.e. for the act itself of vision; and thus vision is not a dowry, but beatitude itself. Secondly, it may be taken habitually, i.e. for the habit whereby this act is elicited, namely the clarity of glory, by which the soul is enlightened from above to see God: and thus it is a dowry and the principle of beatitude, but not beatitude itself. The same answer applies to OBJ 4.

Reply to Objection 5: Beatitude is the sum of all goods not as though they were essential parts of beatitude, but as being in a way directed to beatitude, as stated above.

Whether it is fitting that Christ should receive a dowry?

Objection 1: It would seem fitting that Christ should receive a dowry. For the saints will be conformed to Christ through glory, according to Phil. 3:21, “Who will reform the body of our lowness made like to the body of His glory.” Therefore Christ also will have a dowry.

Objection 2: Further, in the spiritual marriage a dowry is given in likeness to a carnal marriage. Now there is a spiritual marriage in Christ, which is peculiar to Him, namely of the two natures in one Person, in regard to which the human nature in Him is said to have been espoused by the Word, as a gloss [*St. Augustine, De Consensu Evang. i, 40] has it on Ps. 18:6, “He hath set His tabernacle in the sun,” etc., and Apoc. 21:3, “Behold the tabernacle of God with men.” Therefore it is fitting that Christ should have a dowry.

Objection 3: Further, Augustine says (De Doctr. Christ. iii) that Christ, according to the Rule [*Liber regularum] of Tyconius, on account of the unity of the mystic body that exists between the head and its members, calls Himself also the Bride and not only the Bridegroom, as may be gathered from Is. 61:10, “As a bridegroom decked with a crown, and as a bride adorned with her jewels.” Since then a dowry is due to the bride, it would seem that Christ ought to receive a dowry.

Objection 4: Further, a dowry is due to all the members of the Church, since the Church is the spouse. But Christ is a member of the Church according to 1 Cor. 12:27, “You are the body of Christ, and members of member, i.e. of Christ,” according to a gloss. Therefore the dowry is due to Christ.

Objection 5: Further, Christ has perfect vision, fruition, and joy. Now these are the dowries. Therefore, etc.

On the contrary, A distinction of persons is requisite between the bridegroom and the bride. But in Christ there is nothing personally distinct from the Son of God Who is the Bridegroom, as stated in Jn. 3:29, “He that hath the bride is the bridegroom.” Therefore since the dowry is allotted to the bride or for the bride, it would seem unfitting for Christ to have a dowry.

Further, the same person does not both give and receive a dowry. But it is Christ Who gives spiritual dowries. Therefore it is not fitting that Christ should have a dowry.

I answer that, There are two opinions on this point. For some say that there is a threefold union in Christ. One is the union of concord, whereby He is united to God in the bond of love; another is the union of condescension, whereby the human nature is united to the Divine; the third is the union whereby Christ is united to the Church. They say, then, that as regards the first two unions it is fitting for Christ to have the dowries as such, but as regards the third, it is fitting for Him to have the dowries in the most excellent degree, considered as to that in which they consist, but not considered as dowries; because in this union Christ is the bridegroom and the Church the bride, and a dowry is given to the bride as regards property and control, although it is given to the bridegroom as to use. But this does not seem congruous. For in the union of Christ with the Father by the concord of love, even if we consider Him as God, there is not said to be a marriage, since it implies no subjection such as is required in the bride towards the bridegroom. Nor again in the union of the human nature with the Divine, whether we consider the Personal union or that which regards the conformity of will, can there be a dowry, properly speaking, for three reasons. First, because in a marriage where a dowry is given there should be likeness of nature between bridegroom and bride, and this is lacking in the union of the human nature with the Divine; secondly, because there is required a distinction of persons, and the human nature is not personally distinct from the Word; thirdly, because a dowry is given when the bride is first taken to the dwelling of the bridegroom and thus would seem to belong to the bride, who from being not united becomes united; whereas the human nature, which was assumed into the unity of Person by the Word, never was otherwise than perfectly united. Wherefore in the opinion of others we should say that the notion of dowry is either altogether unbecoming to Christ, or not so properly as to the saints; but that the things which we call dowries befit Him in the highest degree.

Reply to Objection 1: This conformity must be understood to refer to the thing which is a dowry and not to the notion of a dowry being in Christ: for it is not requisite that the thing in which we are conformed to Christ should be in the same way in Christ and in us.

Reply to Objection 2: Human nature is not properly said to be a bride in its union with the Word, since the distinction of persons, which is requisite between bridegroom and bride, is not observed therein. That human nature is sometimes described as being espoused in reference to its union with the Word is because it has a certain act of the bride, in that it is united to the Bridegroom inseparably, and in this union is subject to the Word and ruled by the Word, as the bride by the bridegroom.

Reply to Objection 3: If Christ is sometimes spoken of as the Bride, this is not because He is the Bride in very truth, but in so far as He personifies His spouse, namely the Church, who is united to Him spiritually. Hence nothing hinders Him, in this way of speaking, from being said to have the dowries, not that He Himself is dowered, but the Church.

Reply to Objection 4: The term Church is taken in two senses. For sometimes it denotes the body only, which is united to Christ as its Head. In this way alone has the Church the character of spouse: and in this way Christ is not a member of the Church, but is the Head from which all the members receive. In another sense the Church denotes the head and members united together; and thus Christ is said to be a member of the Church, inasmuch as He fulfills an office distinct from all others, by pouring forth life into the other members: although He is not very properly called a member, since a member implies a certain restriction, whereas in Christ spiritual good is not restricted but is absolutely entire [*Cf. [5139]TP, Q[8], A[1]], so that He is the entire good of the Church, nor is He together with others anything greater than He is by Himself. Speaking of the Church in this sense, the Church denotes not only the bride, but the bridegroom and bride, in so far as one thing results from their spiritual union. Consequently although Christ be called a member of the Church in a certain sense, He can by no means be called a member of the bride; and therefore the idea of a dowry is not becoming to Him.

Reply to Objection 5: There is here a fallacy of “accident”; for these things are not befitting to Christ if we consider them under the aspect of dowry.

Whether the angels receive the dowries?

Objection 1: It would seem that the angels receive dowries. For a gloss on Canticle of Canticles 6:8, “One is my dove,” says: “One is the Church among men and angels.” But the Church is the bride, wherefore it is fitting for the members of the Church to have the dowries. Therefore the angels have the dowries.

Objection 2: Further, a gloss on Lk. 12:36, “And you yourselves like to men who wait for their lord, when he shall return from the wedding,” says: “Our Lord went to the wedding when after His resurrection the new Man espoused to Himself the angelic host.” Therefore the angelic hosts are the spouse of Christ and consequently it is fitting that they should have the dowries.

Objection 3: Further, the spiritual marriage consists in a spiritual union. Now the spiritual union between the angels and God is no less than between beatified men and God. Since, then, the dowries of which we treat now are assigned by reason of a spiritual marriage, it would seem that they are becoming to the angels.

Objection 4: Further, a spiritual marriage demands a spiritual bridegroom and a spiritual bride. Now the angels are by nature more conformed than men to Christ as the supreme spirit. Therefore a spiritual marriage is more possible between the angels and Christ than between men and Christ.

Objection 5: Further, a greater conformity is required between the head and members than between bridegroom and bride. Now the conformity between Christ and the angels suffices for Christ to be called the Head of the angels. Therefore for the same reason it suffices for Him to be called their bridegroom.

On the contrary, Origen at the beginning of the prologue to his commentary on the Canticles, distinguishes four persons, namely “the bridegroom with the bride, the young maidens, and the companions of the bridegroom”: and he says that “the angels are the companions of the bridegroom.” Since then the dowry is due only to the bride, it would seem that the dowries are not becoming to the angels.

Further, Christ espoused the Church by His Incarnation and Passion: wherefore this is foreshadowed in the words (Ex. 4:25), “A bloody spouse thou art to me.” Now by His Incarnation and Passion Christ was not otherwise united to the angels than before. Therefore the angels do not belong to the Church, if we consider the Church as spouse. Therefore the dowries are not becoming to the angels.

I answer that, Without any doubt, whatever pertains to the endowments of the soul is befitting to the angels as it is to men. But considered under the aspect of dowry they are not as becoming to the angels as to men, because the character of bride is not so properly becoming to the angels as to men. For there is required a conformity of nature between bridegroom and bride, to wit that they should be of the same species. Now men are in conformity with Christ in this way, since He took human nature, and by so doing became conformed to all men in the specific nature of man. on the other hand, He is not conformed to the angels in unity of species, neither as to His Divine nor as to His human nature. Consequently the notion of dowry is not so properly becoming to angels as to men. Since, however, in metaphorical expressions, it is not necessary to have a likeness in every respect, we must not argue that one thing is not to be said of another metaphorically on account of some lack of likeness; and consequently the argument we have adduced does not prove that the dowries are simply unbecoming to the angels, but only that they are not so properly befitting to angels as to men, on account of the aforesaid lack of likeness.

Reply to Objection 1: Although the angels are included in the unity of the Church, they are not members of the Church according to conformity of nature, if we consider the Church as bride: and thus it is not properly fitting for them to have the dowries.

Reply to Objection 2: Espousal is taken there in a broad sense, for union without conformity of specific nature: and in this sense nothing prevents our saying that the angels have the dowries taking these in a broad sense.

Reply to Objection 3: In the spiritual marriage although there is no other than a spiritual union, those whose union answers to the idea of a perfect marriage should agree in specific nature. Hence espousal does not properly befit the angels.

Reply to Objection 4: The conformity between the angels and Christ as God is not such as suffices for the notion of a perfect marriage, since so far are they from agreeing in species that there is still an infinite distance between them.

Reply to Objection 5: Not even is Christ properly called the Head of the angels, if we consider the head as requiring conformity of nature with the members. We must observe, however, that although the head and the other members are parts of an individual of one species, if we consider each one by itself, it is not of the same species as another member, for a hand is another specific part from the head. Hence, speaking of the members in themselves, the only conformity required among them is one of proportion, so that one receive from another, and one serve another. Consequently the conformity between God and the angels suffices for the notion of head rather than for that of bridegroom.

Whether three dowries of the soul are suitably assigned?

Objection 1: It would seem unfitting to assign to the soul three dowries, namely, “vision,” “love” and “fruition.” For the soul is united to God according to the mind wherein is the image of the Trinity in respect of the memory, understanding, and will. Now love regards the will, and vision the understanding. Therefore there should be something corresponding to the memory, since fruition regards not the memory but the will.

Objection 2: Further, the beatific dowries are said to correspond to the virtues of the way, which united us to God: and these are faith, hope, and charity, whereby God Himself is the object. Now love corresponds to charity, and vision to faith. Therefore there should be something corresponding to hope, since fruition corresponds rather to charity.

Objection 3: Further, we enjoy God by love and vision only, since “we are said to enjoy those things which we love for their own sake,” as Augustine says (De Doctr. Christ. i, 4). Therefore fruition should not be reckoned a distinct dowry from love.

Objection 4: Further, comprehension is required for the perfection of beatitude: “So run that you may comprehend” (1 Cor. 9:24). Therefore we should reckon a fourth dowry

Objection 5: Further, Anselm says (De Simil. xlviii) that the following pertain to the soul’s beatitude: “wisdom, friendship, concord, power, honor, security, joy”: and consequently the aforesaid dowries are reckoned unsuitably.

Objection 6: Further, Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xxii) that “in that beatitude God will be seen unendingly, loved without wearying, praised untiringly.” Therefore praise should be added to the aforesaid dowries.

Objection 7: Further, Boethius reckons five things pertaining to beatitude (De Consol. iii) and these are: Sufficiency which wealth offers, joy which pleasure offers, celebrity which fame offers, security which power offers, reverence which dignity offers. Consequently it seems that these should be reckoned as dowries rather than the aforesaid.

I answer that, All agree in reckoning three dowries of the soul, in different ways however. For some say that the three dowries of the soul are vision, love, and fruition. others reckon them to be vision, comprehension, and fruition; others, vision, delight, and comprehension. However, all these reckonings come to the same, and their number is assigned in the same way. For it has been said [5140](A[2]) that a dowry is something inherent to the soul, and directing it to the operation in which beatitude consists. Now two things are requisite in this operation: its essence which is vision, and its perfection which is delight: since beatitude must needs be a perfect operation. Again, a vision is delightful in two ways: first, on the part of the object, by reason of the thing seen being delightful; secondly, on the part of the vision, by reason of the seeing itself being delightful, even as we delight in knowing evil things, although the evil things themselves delight us not. And since this operation wherein ultimate beatitude consists must needs be most perfect, this vision must needs be delightful in both ways. Now in order that this vision be delightful on the part of the vision, it needs to be made connatural to the seer by means of a habit; while for it to be delightful on the part of the visible object, two things are necessary, namely that the visible object be suitable, and that it be united to the seer. Accordingly for the vision to be delightful on its own part a habit is required to elicit the vision, and thus we have one dowry, which all call vision. But on the part of the visible object two things are necessary. First, suitableness, which regards the affections—and in this respect some reckon love as a dowry, others fruition (in so far as fruition regards the affective part) since what we love most we deem most suitable. Secondly, union is required on the part of the visible object, and thus some reckon comprehension, which is nothing else than to have God present and to hold Him within ourself [*Cf. [5141]FS, Q[4], A[3]]; while others reckon fruition, not of hope, which is ours while on the way, but of possession [*Literally “of the reality: non spei . . . sed rei”] which is in heaven.

Thus the three dowries correspond to the three theological virtues, namely vision to faith, comprehension (or fruition in one sense) to hope, and fruition (or delight according to another reckoning to charity). For perfect fruition such as will be had in heaven includes delight and comprehension, for which reason some take it for the one, and some for the other.

Others, however, ascribe these three dowries to the three powers of the soul, namely vision to the rational, delight to the concupiscible, and fruition to the irascible, seeing that this fruition is acquired by a victory. But this is not said properly, because the irascible and concupiscible powers are not in the intellective but in the sensitive part, whereas the dowries of the soul are assigned to the mind.

Reply to Objection 1: Memory and understanding have but one act: either because understanding is itself an act of memory, or—if understanding denote a power—because memory does not proceed to act save through the medium of the understanding, since it belongs to the memory to retain knowledge. Consequently there is only one habit, namely knowledge, corresponding to memory and understanding: wherefore only one dowry, namely vision, corresponds to both.

Reply to Objection 2: Fruition corresponds to hope, in so far as it includes comprehension which will take the place of hope: since we hope for that which we have not yet; wherefore hope chafes somewhat on account of the distance of the beloved: for which reason it will not remain in heaven [Cf. [5142]SS, Q[18], A[2]] but will be succeeded by comprehension.

Reply to Objection 3: Fruition as including comprehension is distinct from vision and love, but otherwise than love from vision. For love and vision denote different habits, the one belonging to the intellect, the other to the affective faculty. But comprehension, or fruition as denoting comprehension, does not signify a habit distinct from those two, but the removal of the obstacles which made it impossible for the mind to be united to God by actual vision. This is brought about by the habit of glory freeing the soul from all defects; for instance by making it capable of knowledge without phantasms, of complete control over the body, and so forth, thus removing the obstacles which result in our being pilgrims from the Lord.

Reply OBJ 4 is clear from what has been said.

Reply to Objection 5: Properly speaking, the dowries are the immediate principles of the operation in which perfect beatitude consists and whereby the soul is united to Christ. The things mentioned by Anselm do not answer to this description; but they are such as in any way accompany or follow beatitude, not only in relation to the Bridegroom, to Whom “wisdom” alone of the things mentioned by him refers, but also in relation to others. They may be either one’s equals, to whom “friendship” refers as regards the union of affections, and “concord” as regards consent in actions, or one’s inferiors, to whom “power” refers, so far as inferior things are ordered by superior, and “honor” as regards that which inferiors offer to their superiors. Or again (they may accompany or follow beatitude) in relation to oneself: to this “security” refers as regards the removal of evil, and “joy” as regards the attainment of good.

Reply to Objection 6: Praise, which Augustine mentions as the third of those things which will obtain in heaven, is not a disposition to beatitude but rather a sequel to beatitude: because from the very fact of the soul’s union with God, wherein beatitude consists, it follows that the soul breaks forth into praise. Hence praise has not the necessary conditions of a dowry.

Reply to Objection 7: The five things aforesaid mentioned by Boethius are certain conditions of beatitude, but not dispositions to beatitude or to its act, because beatitude by reason of its perfection has of itself alone and undividedly all that men seek in various things, as the Philosopher declares (Ethic. i, 7; x, 7,8). Accordingly Boethius shows that these five things obtain in perfect beatitude, because they are what men seek in temporal happiness. For they pertain either, as “security,” to immunity from evil, or to the attainment either of the suitable good, as “joy,” or of the perfect good, as “sufficiency,” or to the manifestation of good, as “celebrity,” inasmuch as the good of one is made known to others, or as “reverence,” as indicating that good or the knowledge thereof, for reverence is the showing of honor which bears witness to virtue. Hence it is evident that these five should not be called dowries, but conditions of beatitude.

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running