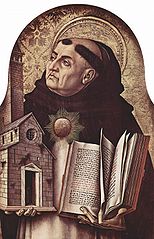

The Summa Theologica by Saint Thomas Aquinas

OF FASTING (EIGHT ARTICLES)

We must now consider fasting: under which head there are eight points of inquiry:

(1) Whether fasting is an act of virtue?

(2) Of what virtue is it the act?

(3) Whether it is a matter of precept?

(4) Whether anyone is excused from fulfilling this precept?

(5) The time of fasting;

(6) Whether it is requisite for fasting to eat but once?

(7) The hour of eating for those who fast;

(8) The meats from which it is necessary to abstain.

Whether fasting is an act of virtue?

Objection 1: It would seem that fasting is not an act of virtue. For every act of virtue is acceptable to God. But fasting is not always acceptable to God, according to Is. 58:3, “Why have we fasted and Thou hast not regarded?” Therefore fasting is not an act of virtue.

Objection 2: Further, no act of virtue forsakes the mean of virtue. Now fasting forsakes the mean of virtue, which in the virtue of abstinence takes account of the necessity of supplying the needs of nature, whereas by fasting something is retrenched therefrom: else those who do not fast would not have the virtue of abstinence. Therefore fasting is not an act of virtue.

Objection 3: Further, that which is competent to all, both good and evil, is not an act of virtue. Now such is fasting, since every one is fasting before eating. Therefore fasting is not an act of virtue.

On the contrary, It is reckoned together with other virtuous acts (2 Cor. 6:5,6) where the Apostle says: “In fasting, in knowledge, in chastity, etc. [Vulg.: ‘in chastity, in knowledge’].”

I answer that, An act is virtuous through being directed by reason to some virtuous [honestum] [*Cf.[3478] Q[145], A[1]] good. Now this is consistent with fasting, because fasting is practiced for a threefold purpose. First, in order to bridle the lusts of the flesh, wherefore the Apostle says (2 Cor. 6:5,6): “In fasting, in chastity,” since fasting is the guardian of chastity. For, according to Jerome [*Contra Jov. ii.] “Venus is cold when Ceres and Bacchus are not there,” that is to say, lust is cooled by abstinence in meat and drink. Secondly, we have recourse to fasting in order that the mind may arise more freely to the contemplation of heavenly things: hence it is related (Dan. 10) of Daniel that he received a revelation from God after fasting for three weeks. Thirdly, in order to satisfy for sins: wherefore it is written (Joel 2:12): “Be converted to Me with all your heart, in fasting and in weeping and in mourning.” The same is declared by Augustine in a sermon (De orat. et Jejun. [*Serm. lxxii (ccxxx, de Tempore)]): “Fasting cleanses the soul, raises the mind, subjects one’s flesh to the spirit, renders the heart contrite and humble, scatters the clouds of concupiscence, quenches the fire of lust, kindles the true light of chastity.”

Reply to Objection 1: An act that is virtuous generically may be rendered vicious by its connection with certain circumstances. Hence the text goes on to say: “Behold in the day of your fast your own will is founded,” and a little further on (Is. 58:4): “You fast for debates and strife and strike with the fist wickedly.” These words are expounded by Gregory (Pastor. iii, 19) as follows: “The will indicates joy and the fist anger. In vain then is the flesh restrained if the mind allowed to drift to inordinate movements be wrecked by vice.” And Augustine says (in the same sermon) that “fasting loves not many words, deems wealth superfluous, scorns pride, commends humility, helps man to perceive what is frail and paltry.”

Reply to Objection 2: The mean of virtue is measured not according to quantity but according to right reason, as stated in Ethic. ii, 6. Now reason judges it expedient, on account of some special motive, for a man to take less food than would be becoming to him under ordinary circumstances, for instance in order to avoid sickness, or in order to perform certain bodily works with greater ease: and much more does reason direct this to the avoidance of spiritual evils and the pursuit of spiritual goods. Yet reason does not retrench so much from one’s food as to refuse nature its necessary support: thus Jerome says:* “It matters not whether thou art a long or a short time in destroying thyself, since to afflict the body immoderately, whether by excessive lack of nourishment, or by eating or sleeping too little, is to offer a sacrifice of stolen goods.” [*The quotation is from the Corpus of Canon Law (Cap. Non mediocriter, De Consecrationibus, dist. 5). Gratian there ascribes the quotation to St. Jerome, but it is not to be found in the saint’s works.] In like manner right reason does not retrench so much from a man’s food as to render him incapable of fulfilling his duty. Hence Jerome says (in the same reference) “Rational man forfeits his dignity, if he sets fasting before chastity, or night-watchings before the well-being of his senses.”

Reply to Objection 3: The fasting of nature, in respect of which a man is said to be fasting until he partakes of food, consists in a pure negation, wherefore it cannot be reckoned a virtuous act. Such is only the fasting of one who abstains in some measure from food for a reasonable purpose. Hence the former is called natural fasting [jejunium jejunii] [*Literally the ‘fast of fasting’]: while the latter is called the faster’s fast, because he fasts for a purpose.

Whether fasting is an act of abstinence?

Objection 1: It would seem that fasting is not an act of abstinence. For Jerome [*The quotation is from the Ordinary Gloss, where the reference is lacking] commenting on Mat. 17:20, “This kind of devil” says: “To fast is to abstain not only from food but also from all manner of lusts.” Now this belongs to every virtue. Therefore fasting is not exclusively an act of abstinence.

Objection 2: Further, Gregory says in a Lenten Homily (xvi in Evang.) that “the Lenten fast is a tithe of the whole year.” Now paying tithes is an act of religion, as stated above ([3479]Q[87], A[1]). Therefore fasting is an act of religion and not of abstinence.

Objection 3: Further, abstinence is a part of temperance, as stated above (QQ[143],146, A[1], ad 3). Now temperance is condivided with fortitude, to which it belongs to endure hardships, and this seems very applicable to fasting. Therefore fasting is not an act of abstinence.

On the contrary, Isidore says (Etym. vi, 19) that “fasting is frugality of fare and abstinence from food.”

I answer that, Habit and act have the same matter. Wherefore every virtuous act about some particular matter belongs to the virtue that appoints the mean in that matter. Now fasting is concerned with food, wherein the mean is appointed by abstinence. Wherefore it is evident that fasting is an act of abstinence.

Reply to Objection 1: Properly speaking fasting consists in abstaining from food, but speaking metaphorically it denotes abstinence from anything harmful, and such especially is sin.

We may also reply that even properly speaking fasting is abstinence from all manner of lust, since, as stated above (A[1], ad 1), an act ceases to be virtuous by the conjunction of any vice.

Reply to Objection 2: Nothing prevents the act of one virtue belonging to another virtue, in so far as it is directed to the end of that virtue, as explained above ([3480]Q[32], A[1], ad 2;[3481] Q[85], A[3]). Accordingly there is no reason why fasting should not be an act of religion, or of chastity, or of any other virtue.

Reply to Objection 3: It belongs to fortitude as a special virtue, to endure, not any kind of hardship, but only those connected with the danger of death. To endure hardships resulting from privation of pleasure of touch, belongs to temperance and its parts: and such are the hardships of fasting.

Whether fasting is a matter of precept?

Objection 1: It would seem that fasting is not a matter of precept. For precepts are not given about works of supererogation which are a matter of counsel. Now fasting is a work of supererogation: else it would have to be equally observed at all places and times. Therefore fasting is not a matter of precept.

Objection 2: Further, whoever infringes a precept commits a mortal sin. Therefore if fasting were a matter of precept, all who do not fast would sin mortally, and a widespreading snare would be laid for men.

Objection 3: Further, Augustine says (De Vera Relig. 17) that “the Wisdom of God having taken human nature, and called us to a state of freedom, instituted a few most salutary sacraments whereby the community of the Christian people, that is, of the free multitude, should be bound together in subjection to one God.” Now the liberty of the Christian people seems to be hindered by a great number of observances no less than by a great number of sacraments. For Augustine says (Ad inquis. Januar., Ep. lv) that “whereas God in His mercy wished our religion to be distinguished by its freedom and the evidence and small number of its solemn sacraments, some people render it oppressive with slavish burdens.” Therefore it seems that the Church should not have made fasting a matter of precept.

On the contrary, Jerome (Ad Lucin., Ep. lxxi) speaking of fasting says: “Let each province keep to its own practice, and look upon the commands of the elders as though they were laws of the apostles.” Therefore fasting is a matter of precept.

I answer that, Just as it belongs to the secular authority to make legal precepts which apply the natural law to matters of common weal in temporal affairs, so it belongs to ecclesiastical superiors to prescribe by statute those things that concern the common weal of the faithful in spiritual goods.

Now it has been stated above [3482](A[1]) that fasting is useful as atoning for and preventing sin, and as raising the mind to spiritual things. And everyone is bound by the natural dictate of reason to practice fasting as far as it is necessary for these purposes. Wherefore fasting in general is a matter of precept of the natural law, while the fixing of the time and manner of fasting as becoming and profitable to the Christian people, is a matter of precept of positive law established by ecclesiastical authority: the latter is the Church fast, the former is the fast prescribed by nature.

Reply to Objection 1: Fasting considered in itself denotes something not eligible but penal: yet it becomes eligible in so far as it is useful to some end. Wherefore considered absolutely it is not binding under precept, but it is binding under precept to each one that stands in need of such a remedy. And since men, for the most part, need this remedy, both because “in many things we all offend” (James 3:2), and because “the flesh lusteth against the spirit” (Gal. 5:17), it was fitting that the Church should appoint certain fasts to be kept by all in common. In doing this the Church does not make a precept of a matter of supererogation, but particularizes in detail that which is of general obligation.

Reply to Objection 2: Those commandments which are given under the form of a general precept, do not bind all persons in the same way, but subject to the requirements of the end intended by the lawgiver. It will be a mortal sin to disobey a commandment through contempt of the lawgiver’s authority, or to disobey it in such a way as to frustrate the end intended by him: but it is not a mortal sin if one fails to keep a commandment, when there is a reasonable motive, and especially if the lawgiver would not insist on its observance if he were present. Hence it is that not all, who do not keep the fasts of the Church, sin mortally.

Reply to Objection 3: Augustine is speaking there of those things “that are neither contained in the authorities of Holy Scripture, nor found among the ordinances of bishops in council, nor sanctioned by the custom of the universal Church.” On the other hand, the fasts that are of obligation are appointed by the councils of bishops and are sanctioned by the custom of the universal Church. Nor are they opposed to the freedom of the faithful, rather are they of use in hindering the slavery of sin, which is opposed to spiritual freedom, of which it is written (Gal. 5:13): “You, brethren, have been called unto liberty; only make not liberty an occasion to the flesh.”

Whether all are bound to keep the fasts of the Church?

Objection 1: It would seem that all are bound to keep the fasts of the Church. For the commandments of the Church are binding even as the commandments of God, according to Lk. 10:16, “He that heareth you heareth Me.” Now all are bound to keep the commandments of God. Therefore in like manner all are bound to keep the fasts appointed by the Church.

Objection 2: Further, children especially are seemingly not exempt from fasting, on account of their age: for it is written (Joel 2:15): “Sanctify a fast,” and further on (Joel 2:16): “Gather together the little ones, and them that suck the breasts.” Much more therefore are all others bound to keen the fasts.

Objection 3: Further, spiritual things should be preferred to temporal, and necessary things to those that are not necessary. Now bodily works are directed to temporal gain; and pilgrimages, though directed to spiritual things, are not a matter of necessity. Therefore, since fasting is directed to a spiritual gain, and is made a necessary thing by the commandment of the Church, it seems that the fasts of the Church ought not to be omitted on account of a pilgrimage, or bodily works.

Objection 4: Further, it is better to do a thing willingly than through necessity, as stated in 2 Cor. 9:7. Now the poor are wont to fast through necessity, owing to lack of food. Much more therefore ought they to fast willingly.

On the contrary, It seems that no righteous man is bound to fast. For the commandments of the Church are not binding in opposition to Christ’s teaching. But our Lord said (Lk. 5:34) that “the children of the bridegroom cannot fast whilst the bridegroom is with them [*Vulg.: ‘Can you make the children of the bridegroom fast, whilst the bridegroom is with them?’].” Now He is with all the righteous by dwelling in them in a special manner [*Cf. [3483]FP, Q[8], A[3]], wherefore our Lord said (Mat. 28:20): “Behold I am with you . . . even to the consummation of the world.” Therefore the righteous are not bound by the commandment of the Church to fast.

I answer that, As stated above ([3484]FS, Q[90], A[2]; [3485]FS, Q[98], AA[2],6), general precepts are framed according to the requirements of the many. Wherefore in making such precepts the lawgiver considers what happens generally and for the most part, and he does not intend the precept to be binding on a person in whom for some special reason there is something incompatible with observance of the precept. Yet discretion must be brought to bear on the point. For if the reason be evident, it is lawful for a man to use his own judgment in omitting to fulfil the precept, especially if custom be in his favor, or if it be difficult for him to have recourse to superior authority. on the other hand, if the reason be doubtful, one should have recourse to the superior who has power to grant a dispensation in such cases. And this must be done in the fasts appointed by the Church, to which all are bound in general, unless there be some special obstacle to this observance.

Reply to Objection 1: The commandments of God are precepts of the natural law, which are, of themselves, necessary for salvation. But the commandments of the Church are about matters which are necessary for salvation, not of themselves, but only through the ordinance of the Church. Hence there may be certain obstacles on account of which certain persons are not bound to keep the fasts in question.

Reply to Objection 2: In children there is a most evident reason for not fasting, both on account of their natural weakness, owing to which they need to take food frequently, and not much at a time, and because they need much nourishment owing to the demands of growth, which results from the residuum of nourishment. Wherefore as long as the stage of growth lasts, which as a rule lasts until they have completed the third period of seven years, they are not bound to keep the Church fasts: and yet it is fitting that even during that time they should exercise themselves in fasting, more or less, in accordance with their age. Nevertheless when some great calamity threatens, even children are commanded to fast, in sign of more severe penance, according to Jonah 3:7, “Let neither men nor beasts . . . taste anything . . . nor drink water.”

Reply to Objection 3: Apparently a distinction should be made with regard to pilgrims and working people. For if the pilgrimage or laborious work can be conveniently deferred or lessened without detriment to the bodily health and such external conditions as are necessary for the upkeep of bodily or spiritual life, there is no reason for omitting the fasts of the Church. But if one be under the necessity of starting on the pilgrimage at once, and of making long stages, or of doing much work, either for one’s bodily livelihood, or for some need of the spiritual life, and it be impossible at the same time to keep the fasts of the Church, one is not bound to fast: because in ordering fasts the Church would not seem to have intended to prevent other pious and more necessary undertakings. Nevertheless, in such cases one ought seemingly, to seek the superior’s dispensation; except perhaps when the above course is recognized by custom, since when superiors are silent they would seem to consent.

Reply to Objection 4: Those poor who can provide themselves with sufficient for one meal are not excused, on account of poverty, from keeping the fasts of the Church. On the other hand, those would seem to be exempt who beg their food piecemeal, since they are unable at any one time to have a sufficiency of food.

Reply to Objection 5: This saying of our Lord may be expounded in three ways. First, according to Chrysostom (Hom. xxx in Matth.), who says that “the disciples, who are called children of the bridegroom, were as yet of a weakly disposition, wherefore they are compared to an old garment.” Hence while Christ was with them in body they were to be fostered with kindness rather than drilled with the harshness of fasting. According to this interpretation, it is fitting that dispensations should be granted to the imperfect and to beginners, rather than to the elders and the perfect, according to a gloss on Ps. 130:2, “As a child that is weaned is towards his mother.” Secondly, we may say with Jerome [*Bede, Comment. in Luc. v] that our Lord is speaking here of the fasts of the observances of the Old Law. Wherefore our Lord means to say that the apostles were not to be held back by the old observances, since they were to be filled with the newness of grace. Thirdly, according to Augustine (De Consensu Evang. ii, 27), who states that fasting is of two kinds. one pertains to those who are humbled by disquietude, and this is not befitting perfect men, for they are called “children of the bridegroom”; hence when we read in Luke: “The children of the bridegroom cannot fast [*Hom. xiii, in Matth.],” we read in Mat. 9:15: “The children of the bridegroom cannot mourn [*Vulg.: ‘Can the children of the bridegroom mourn?’].” The other pertains to the mind that rejoices in adhering to spiritual things: and this fasting is befitting the perfect.

Whether the times for the Church fast are fittingly ascribed?

Objection 1: It would seem that the times for the Church fast are unfittingly appointed. For we read (Mat. 4) that Christ began to fast immediately after being baptized. Now we ought to imitate Christ, according to 1 Cor. 4:16, “Be ye followers of me, as I also am of Christ.” Therefore we ought to fast immediately after the Epiphany when Christ’s baptism is celebrated.

Objection 2: Further, it is unlawful in the New Law to observe the ceremonies of the Old Law. Now it belongs to the solemnities of the Old Law to fast in certain particular months: for it is written (Zech. 8:19): “The fast of the fourth month and the fast of the fifth, and the fast of the seventh, and the fast of the tenth shall be to the house of Judah, joy and gladness and great solemnities.” Therefore the fast of certain months, which are called Ember days, are unfittingly kept in the Church.

Objection 3: Further, according to Augustine (De Consensu Evang. ii, 27), just as there is a fast “of sorrow,” so is there a fast “of joy.” Now it is most becoming that the faithful should rejoice spiritually in Christ’s Resurrection. Therefore during the five weeks which the Church solemnizes on account of Christ’s Resurrection, and on Sundays which commemorate the Resurrection, fasts ought to be appointed.

On the contrary, stands the general custom of the Church.

I answer that, As stated above ([3486]AA[1],3), fasting is directed to two things, the deletion of sin, and the raising of the mind to heavenly things. Wherefore fasting ought to be appointed specially for those times, when it behooves man to be cleansed from sin, and the minds of the faithful to be raised to God by devotion: and these things are particularly requisite before the feast of Easter, when sins are loosed by baptism, which is solemnly conferred on Easter-eve, on which day our Lord’s burial is commemorated, because “we are buried together with Christ by baptism unto death” (Rom. 6:4). Moreover at the Easter festival the mind of man ought to be devoutly raised to the glory of eternity, which Christ restored by rising from the dead, and so the Church ordered a fast to be observed immediately before the Paschal feast; and for the same reason, on the eve of the chief festivals, because it is then that one ought to make ready to keep the coming feast devoutly. Again it is the custom in the Church for Holy orders to be conferred every quarter of the year (in sign whereof our Lord fed four thousand men with seven loaves, which signify the New Testament year as Jerome says [*Comment. in Marc. viii]): and then both the ordainer, and the candidates for ordination, and even the whole people, for whose good they are ordained, need to fast in order to make themselves ready for the ordination. Hence it is related (Lk. 6:12) that before choosing His disciples our Lord “went out into a mountain to pray”: and Ambrose [*Exposit. in Luc.] commenting on these words says: “What shouldst thou do, when thou desirest to undertake some pious work, since Christ prayed before sending His apostles?”

With regard to the forty day’s fast, according to Gregory (Hom. xvi in Evang.) there are three reasons for the number. First, “because the power of the Decalogue is accomplished in the four books of the Holy Gospels: since forty is the product of ten multiplied by four.” Or “because we are composed of four elements in this mortal body through whose lusts we transgress the Lord’s commandments which are delivered to us in the Decalogue. Wherefore it is fitting we should punish that same body forty times. or, because, just as under the Law it was commanded that tithes should be paid of things, so we strive to pay God a tithe of days, for since a year is composed of three hundred and sixty-six days, by punishing ourselves for thirty-six days” (namely, the fasting days during the six weeks of Lent) “we pay God a tithe of our year.” According to Augustine (De Doctr. Christ. ii, 16) a fourth reason may be added. For the Creator is the “Trinity,” Father, Son, and Holy Ghost: while the number “three” refers to the invisible creature, since we are commanded to love God, with our whole heart, with our whole soul, and with our whole mind: and the number “four” refers to the visible creature, by reason of heat, cold, wet and dry. Thus the number “ten” [*Ten is the sum of three, three, and four] signifies all things, and if this be multiplied by four which refers to the body whereby we make use of things, we have the number forty.

Each fast of the Ember days is composed of three days, on account of the number of months in each season: or on account of the number of Holy orders which are conferred at these times.

Reply to Objection 1: Christ needed not baptism for His own sake, but in order to commend baptism to us. Wherefore it was competent for Him to fast, not before, but after His baptism, in order to invite us to fast before our baptism.

Reply to Objection 2: The Church keeps the Ember fasts, neither at the very same time as the Jews, nor for the same reasons. For they fasted in July, which is the fourth month from April (which they count as the first), because it was then that Moses coming down from Mount Sinai broke the tables of the Law (Ex. 32), and that, according to Jer. 39:2, “the walls of the city were first broken through.” In the fifth month, which we call August, they fasted because they were commanded not to go up on to the mountain, when the people had rebelled on account of the spies (Num. 14): also in this month the temple of Jerusalem was burnt down by Nabuchodonosor (Jer. 52) and afterwards by Titus. In the seventh month which we call October, Godolias was slain, and the remnants of the people were dispersed (Jer. 51). In the tenth month, which we call January, the people who were with Ezechiel in captivity heard of the destruction of the temple (Ezech. 4).

Reply to Objection 3: The “fasting of joy” proceeds from the instigation of the Holy Ghost Who is the Spirit of liberty, wherefore this fasting should not be a matter of precept. Accordingly the fasts appointed by the commandment of the Church are rather “fasts of sorrow” which are inconsistent with days of joy. For this reason fasting is not ordered by the Church during the whole of the Paschal season, nor on Sundays: and if anyone were to fast at these times in contradiction to the custom of Christian people, which as Augustine declares (Ep. xxxvi) “is to be considered as law,” or even through some erroneous opinion (thus the Manichees fast, because they deem such fasting to be of obligation)—he would not be free from sin. Nevertheless fasting considered in itself is commendable at all times; thus Jerome wrote (Ad Lucin., Ep. lxxi): “Would that we might fast always.”

Whether it is requisite for fasting that one eat but once?

Objection 1: It would seem that it is not requisite for fasting that one eat but once. For, as stated above [3487](A[2]), fasting is an act of the virtue of abstinence, which observes due quantity of food not less than the number of meals. Now the quantity of food is not limited for those who fast. Therefore neither should the number of meals be limited.

Objection 2: Further, Just as man is nourished by meat, so is he by drink: wherefore drink breaks the fast, and for this reason we cannot receive the Eucharist after drinking. Now we are not forbidden to drink at various hours of the day. Therefore those who fast should not be forbidden to eat several times.

Objection 3: Further, digestives are a kind of food: and yet many take them on fasting days after eating. Therefore it is not essential to fasting to take only one meal.

On the contrary, stands the common custom of the Christian people.

I answer that, Fasting is instituted by the Church in order to bridle concupiscence, yet so as to safeguard nature. Now only one meal is seemingly sufficient for this purpose, since thereby man is able to satisfy nature; and yet he withdraws something from concupiscence by minimizing the number of meals. Therefore it is appointed by the Church, in her moderation, that those who fast should take one meal in the day.

Reply to Objection 1: It was not possible to fix the same quantity of food for all, on account of the various bodily temperaments, the result being that one person needs more, and another less food: whereas, for the most part, all are able to satisfy nature by only one meal.

Reply to Objection 2: Fasting is of two kinds [*Cf. A[1], ad 3]. One is the natural fast, which is requisite for receiving the Eucharist. This is broken by any kind of drink, even of water, after which it is not lawful to receive the Eucharist. The fast of the Church is another kind and is called the “fasting of the faster,” and this is not broken save by such things as the Church intended to forbid in instituting the fast. Now the Church does not intend to command abstinence from drink, for this is taken more for bodily refreshment, and digestion of the food consumed, although it nourishes somewhat. It is, however, possible to sin and lose the merit of fasting, by partaking of too much drink: as also by eating immoderately at one meal.

Reply to Objection 3: Although digestives nourish somewhat they are not taken chiefly for nourishment, but for digestion. Hence one does not break one’s fast by taking them or any other medicines, unless one were to take digestives, with a fraudulent intention, in great quantity and by way of food.

Whether the ninth hour is suitably fixed for the faster’s meal?

Objection 1: It would seem that the ninth hour is not suitably fixed for the faster’s meal. For the state of the New Law is more perfect than the state of the Old Law. Now in the Old Testament they fasted until evening, for it is written (Lev. 23:32): “It is a sabbath . . . you shall afflict your souls,” and then the text continues: “From evening until evening you shall celebrate your sabbaths.” Much more therefore under the New Testament should the fast be ordered until the evening.

Objection 2: Further, the fast ordered by the Church is binding on all. But all are not able to know exactly the ninth hour. Therefore it seems that the fixing of the ninth hour should not form part of the commandment to fast.

Objection 3: Further, fasting is an act of the virtue of abstinence, as stated above [3488](A[2]). Now the mean of moral virtue does not apply in the same way to all, since what is much for one is little for another, as stated in Ethic. ii, 6. Therefore the ninth hour should not be fixed for those who fast.

On the contrary, The Council of Chalons [*The quotation is from the Capitularies (Cap. 39) of Theodulf, bishop of Orleans (760–821) and is said to be found in the Corpus Juris, Cap. Solent, dist. 1, De Consecratione] says: “During Lent those are by no means to be credited with fasting who eat before the celebration of the office of Vespers,” which in the Lenten season is said after the ninth hour. Therefore we ought to fast until the ninth hour.

I answer that, As stated above ([3489]AA[1],3,5), fasting is directed to the deletion and prevention of sin. Hence it ought to add something to the common custom, yet so as not to be a heavy burden to nature. Now the right and common custom is for men to eat about the sixth hour: both because digestion is seemingly finished (the natural heat being withdrawn inwardly at night-time on account of the surrounding cold of the night), and the humor spread about through the limbs (to which result the heat of the day conduces until the sun has reached its zenith), and again because it is then chiefly that the nature of the human body needs assistance against the external heat that is in the air, lest the humors be parched within. Hence, in order that those who fast may feel some pain in satisfaction for their sins, the ninth hour is suitably fixed for their meal.

Moreover, this hour agrees with the mystery of Christ’s Passion, which was brought to a close at the ninth hour, when “bowing His head, He gave up the ghost” (Jn. 19:30): because those who fast by punishing their flesh, are conformed to the Passion of Christ, according to Gal. 5:24, “They that are Christ’s, have crucified their flesh with the vices and concupiscences.”

Reply to Objection 1: The state of the Old Testament is compared to the night, while the state of the New Testament is compared to the day, according to Rom. 13:12, “The night is passed and the day is at hand.” Therefore in the Old Testament they fasted until night, but not in the New Testament.

Reply to Objection 2: Fasting requires a fixed hour based, not on a strict calculation, but on a rough estimate: for it suffices that it be about the ninth hour, and this is easy for anyone to ascertain.

Reply to Objection 3: A little more or a little less cannot do much harm. Now it is not a long space of time from the sixth hour at which men for the most part are wont to eat, until the ninth hour, which is fixed for those who fast. Wherefore the fixing of such a time cannot do much harm to anyone, whatever his circumstances may be. If however this were to prove a heavy burden to a man on account of sickness, age, or some similar reason, he should be dispensed from fasting, or be allowed to forestall the hour by a little.

Whether it is fitting that those who fast should be bidden to abstain from flesh meat, eggs, and milk foods?

Objection 1: It would seem unfitting that those who fast should be bidden to abstain from flesh meat, eggs, and milk foods. For it has been stated above [3490](A[6]) that fasting was instituted as a curb on the concupiscence of the flesh. Now concupiscence is kindled by drinking wine more than by eating flesh; according to Prov. 20:1, “Wine is a luxurious thing,” and Eph. 5:18, “Be not drunk with wine, wherein is luxury.” Since then those who fast are not forbidden to drink wine, it seems that they should not be forbidden to eat flesh meat.

Objection 2: Further, some fish are as delectable to eat as the flesh of certain animals. Now “concupiscence is desire of the delectable,” as stated above ([3491]FS, Q[30], A[1]). Therefore since fasting which was instituted in order to bridle concupiscence does not exclude the eating of fish, neither should it exclude the eating of flesh meat.

Objection 3: Further, on certain fasting days people make use of eggs and cheese. Therefore one can likewise make use of them during the Lenten fast.

On the contrary, stands the common custom of the faithful.

I answer that, As stated above [3492](A[6]), fasting was instituted by the Church in order to bridle the concupiscences of the flesh, which regard pleasures of touch in connection with food and sex. Wherefore the Church forbade those who fast to partake of those foods which both afford most pleasure to the palate, and besides are a very great incentive to lust. Such are the flesh of animals that take their rest on the earth, and of those that breathe the air and their products, such as milk from those that walk on the earth, and eggs from birds. For, since such like animals are more like man in body, they afford greater pleasure as food, and greater nourishment to the human body, so that from their consumption there results a greater surplus available for seminal matter, which when abundant becomes a great incentive to lust. Hence the Church has bidden those who fast to abstain especially from these foods.

Reply to Objection 1: Three things concur in the act of procreation, namely, heat, spirit [*Cf. P. I., Q. 118, A[1], ad 3], and humor. Wine and other things that heat the body conduce especially to heat: flatulent foods seemingly cooperate in the production of the vital spirit: but it is chiefly the use of flesh meat which is most productive of nourishment, that conduces to the production of humor. Now the alteration occasioned by heat, and the increase in vital spirits are of short duration, whereas the substance of the humor remains a long time. Hence those who fast are forbidden the use of flesh meat rather than of wine or vegetables which are flatulent foods.

Reply to Objection 2: In the institution of fasting, the Church takes account of the more common occurrences. Now, generally speaking, eating flesh meat affords more pleasure than eating fish, although this is not always the case. Hence the Church forbade those who fast to eat flesh meat, rather than to eat fish.

Reply to Objection 3: Eggs and milk foods are forbidden to those who fast, for as much as they originate from animals that provide us with flesh: wherefore the prohibition of flesh meat takes precedence of the prohibition of eggs and milk foods. Again the Lenten fast is the most solemn of all, both because it is kept in imitation of Christ, and because it disposes us to celebrate devoutly the mysteries of our redemption. For this reason the eating of flesh meat is forbidden in every fast, while the Lenten fast lays a general prohibition even on eggs and milk foods. As to the use of the latter things in other fasts the custom varies among different people, and each person is bound to conform to that custom which is in vogue with those among whom he is dwelling. Hence Jerome says [*Augustine, De Lib. Arb. iii, 18; cf. De Nat. et Grat. lxvii]: “Let each province keep to its own practice, and look upon the commands of the elders as though they were the laws of the apostles.”

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running