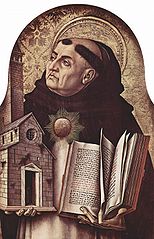

The Summa Theologica by Saint Thomas Aquinas

OF PEACE (FOUR ARTICLES)

We must now consider Peace, under which head there are four points of inquiry:

(1) Whether peace is the same as concord?

(2) Whether all things desire peace?

(3) Whether peace is an effect of charity?

(4) Whether peace is a virtue?

Whether peace is the same as concord?

Objection 1: It would seem that peace is the same as concord. For Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xix, 13): “Peace among men is well ordered concord.” Now we are speaking here of no other peace than that of men. Therefore peace is the same as concord.

Objection 2: Further, concord is union of wills. Now the nature of peace consists in such like union, for Dionysius says (Div. Nom. xi) that peace unites all, and makes them of one mind. Therefore peace is the same as concord.

Objection 3: Further, things whose opposites are identical are themselves identical. Now the one same thing is opposed to concord and peace, viz. dissension; hence it is written (1 Cor. 16:33): “God is not the God of dissension but of peace.” Therefore peace is the same as concord.

On the contrary, There can be concord in evil between wicked men. But “there is no peace to the wicked” (Is. 48:22). Therefore peace is not the same as concord.

I answer that, Peace includes concord and adds something thereto. Hence wherever peace is, there is concord, but there is not peace, wherever there is concord, if we give peace its proper meaning.

For concord, properly speaking, is between one man and another, in so far as the wills of various hearts agree together in consenting to the same thing. Now the heart of one man may happen to tend to diverse things, and this in two ways. First, in respect of the diverse appetitive powers: thus the sensitive appetite tends sometimes to that which is opposed to the rational appetite, according to Gal. 5:17: “The flesh lusteth against the spirit.” Secondly, in so far as one and the same appetitive power tends to diverse objects of appetite, which it cannot obtain all at the same time: so that there must needs be a clashing of the movements of the appetite. Now the union of such movements is essential to peace, because man’s heart is not at peace, so long as he has not what he wants, or if, having what he wants, there still remains something for him to want, and which he cannot have at the same time. On the other hand this union is not essential to concord: wherefore concord denotes union of appetites among various persons, while peace denotes, in addition to this union, the union of the appetites even in one man.

Reply to Objection 1: Augustine is speaking there of that peace which is between one man and another, and he says that this peace is concord, not indeed any kind of concord, but that which is well ordered, through one man agreeing with another in respect of something befitting to both of them . For if one man concord with another, not of his own accord, but through being forced, as it were, by the fear of some evil that besets him, such concord is not really peace, because the order of each concordant is not observed, but is disturbed by some fear-inspiring cause. For this reason he premises that “peace is tranquillity of order,” which tranquillity consists in all the appetitive movements in one man being set at rest together.

Reply to Objection 2: If one man consent to the same thing together with another man, his consent is nevertheless not perfectly united to himself, unless at the same time all his appetitive movements be in agreement.

Reply to Objection 3: A twofold dissension is opposed to peace, namely dissension between a man and himself, and dissension between one man and another. The latter alone is opposed to concord.

Whether all things desire peace?

Objection 1: It would seem that not all things desire peace. For, according to Dionysius (Div. Nom. xi), peace “unites consent.” But there cannot be unity of consent in things which are devoid of knowledge. Therefore such things cannot desire peace.

Objection 2: Further, the appetite does not tend to opposite things at the same time. Now many desire war and dissension. Therefore all men do not desire peace.

Objection 3: Further, good alone is an object of appetite. But a certain peace is, seemingly, evil, else Our Lord would not have said (Mat. 10:34): “I came not to send peace.” Therefore all things do not desire peace.

Objection 4: Further, that which all desire is, seemingly, the sovereign good which is the last end. But this is not true of peace, since it is attainable even by a wayfarer; else Our Lord would vainly command (Mk. 9:49): “Have peace among you.” Therefore all things do not desire peace.

On the contrary, Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xix, 12,14) that “all things desire peace”: and Dionysius says the same (Div. Nom. xi).

I answer that, From the very fact that a man desires a certain thing it follows that he desires to obtain what he desires, and, in consequence, to remove whatever may be an obstacle to his obtaining it. Now a man may be hindered from obtaining the good he desires, by a contrary desire either of his own or of some other, and both are removed by peace, as stated above. Hence it follows of necessity that whoever desires anything desires peace, in so far as he who desires anything, desires to attain, with tranquillity and without hindrance, to that which he desires: and this is what is meant by peace which Augustine defines (De Civ. Dei xix, 13) “the tranquillity of order.”

Reply to Objection 1: Peace denotes union not only of the intellective or rational appetite, or of the animal appetite, in both of which consent may be found, but also of the natural appetite. Hence Dionysius says that “peace is the cause of consent and of connaturalness,” where “consent” denotes the union of appetites proceeding from knowledge, and “connaturalness,” the union of natural appetites.

Reply to Objection 2: Even those who seek war and dissension, desire nothing but peace, which they deem themselves not to have. For as we stated above, there is no peace when a man concords with another man counter to what he would prefer. Consequently men seek by means of war to break this concord, because it is a defective peace, in order that they may obtain peace, where nothing is contrary to their will. Hence all wars are waged that men may find a more perfect peace than that which they had heretofore.

Reply to Objection 3: Peace gives calm and unity to the appetite. Now just as the appetite may tend to what is good simply, or to what is good apparently, so too, peace may be either true or apparent. There can be no true peace except where the appetite is directed to what is truly good, since every evil, though it may appear good in a way, so as to calm the appetite in some respect, has, nevertheless many defects, which cause the appetite to remain restless and disturbed. Hence true peace is only in good men and about good things. The peace of the wicked is not a true peace but a semblance thereof, wherefore it is written (Wis. 14:22): “Whereas they lived in a great war of ignorance, they call so many and so great evils peace.”

Reply to Objection 4: Since true peace is only about good things, as the true good is possessed in two ways, perfectly and imperfectly, so there is a twofold true peace. One is perfect peace. It consists in the perfect enjoyment of the sovereign good, and unites all one’s desires by giving them rest in one object. This is the last end of the rational creature, according to Ps. 147:3: “Who hath placed peace in thy borders.” The other is imperfect peace, which may be had in this world, for though the chief movement of the soul finds rest in God, yet there are certain things within and without which disturb the peace.

Whether peace is the proper effect of charity?

Objection 1: It would seem that peace is not the proper effect of charity. For one cannot have charity without sanctifying grace. But some have peace who have not sanctifying grace, thus heathens sometimes have peace. Therefore peace is not the effect of charity.

Objection 2: Further, if a certain thing is caused by charity, its contrary is not compatible with charity. But dissension, which is contrary to peace, is compatible with charity, for we find that even holy doctors, such as Jerome and Augustine, dissented in some of their opinions. We also read that Paul and Barnabas dissented from one another (Acts 15). Therefore it seems that peace is not the effect of charity.

Objection 3: Further, the same thing is not the proper effect of different things. Now peace is the effect of justice, according to Is. 32:17: “And the work of justice shall be peace.” Therefore it is not the effect of charity.

On the contrary, It is written (Ps. 118:165): “Much peace have they that love Thy Law.”

I answer that, Peace implies a twofold union, as stated above [2586](A[1]). The first is the result of one’s own appetites being directed to one object; while the other results from one’s own appetite being united with the appetite of another: and each of these unions is effected by charity—the first, in so far as man loves God with his whole heart, by referring all things to Him, so that all his desires tend to one object—the second, in so far as we love our neighbor as ourselves, the result being that we wish to fulfil our neighbor’s will as though it were ours: hence it is reckoned a sign of friendship if people “make choice of the same things” (Ethic. ix, 4), and Tully says (De Amicitia) that friends “like and dislike the same things” (Sallust, Catilin.)

Reply to Objection 1: Without sin no one falls from a state of sanctifying grace, for it turns man away from his due end by making him place his end in something undue: so that his appetite does not cleave chiefly to the true final good, but to some apparent good. Hence, without sanctifying grace, peace is not real but merely apparent.

Reply to Objection 2: As the Philosopher says (Ethic. ix, 6) friends need not agree in opinion, but only upon such goods as conduce to life, and especially upon such as are important; because dissension in small matters is scarcely accounted dissension. Hence nothing hinders those who have charity from holding different opinions. Nor is this an obstacle to peace, because opinions concern the intellect, which precedes the appetite that is united by peace. In like manner if there be concord as to goods of importance, dissension with regard to some that are of little account is not contrary to charity: for such a dissension proceeds from a difference of opinion, because one man thinks that the particular good, which is the object of dissension, belongs to the good about which they agree, while the other thinks that it does not. Accordingly such like dissension about very slight matters and about opinions is inconsistent with a state of perfect peace, wherein the truth will be known fully, and every desire fulfilled; but it is not inconsistent with the imperfect peace of the wayfarer.

Reply to Objection 3: Peace is the “work of justice” indirectly, in so far as justice removes the obstacles to peace: but it is the work of charity directly, since charity, according to its very nature, causes peace. For love is “a unitive force” as Dionysius says (Div. Nom. iv): and peace is the union of the appetite’s inclinations.

Whether peace is a virtue?

Objection 1: It would seem that peace is a virtue. For nothing is a matter of precept, unless it be an act of virtue. But there are precepts about keeping peace, for example: “Have peace among you” (Mk. 9:49). Therefore peace is a virtue.

Objection 2: Further, we do not merit except by acts of virtue. Now it is meritorious to keep peace, according to Mat. 5:9: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.” Therefore peace is a virtue.

Objection 3: Further, vices are opposed to virtues. But dissensions, which are contrary to peace, are numbered among the vices (Gal. 5:20). Therefore peace is a virtue.

On the contrary, Virtue is not the last end, but the way thereto. But peace is the last end, in a sense, as Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xix, 11). Therefore peace is not a virtue.

I answer that, As stated above ([2587]Q[28], A[4]), when a number of acts all proceeding uniformly from an agent, follow one from the other, they all arise from the same virtue, nor do they each have a virtue from which they proceed, as may be seen in corporeal things. For, though fire by heating, both liquefies and rarefies, there are not two powers in fire, one of liquefaction, the other of rarefaction: and fire produces all such actions by its own power of calefaction.

Since then charity causes peace precisely because it is love of God and of our neighbor, as shown above [2588](A[3]), there is no other virtue except charity whose proper act is peace, as we have also said in reference to joy (Q[28], A[4]).

Reply to Objection 1: We are commanded to keep peace because it is an act of charity; and for this reason too it is a meritorious act. Hence it is placed among the beatitudes, which are acts of perfect virtue, as stated above ([2589]FS, Q[69], AA[1],3). It is also numbered among the fruits, in so far as it is a final good, having spiritual sweetness.

This suffices for the Reply to the Second Objection.

Reply to Objection 3: Several vices are opposed to one virtue in respect of its various acts: so that not only is hatred opposed to charity, in respect of its act which is love, but also sloth and envy, in respect of joy, and dissension in respect of peace.

OF MERCY (FOUR ARTICLES) [*The one Latin word “misericordia” signifies either pity or mercy. The distinction between these two is that pity may stand either for the act or for the virtue, whereas mercy stands only for the virtue.]

We must now go on to consider Mercy, under which head there are four points of inquiry:

(1) Whether evil is the cause of mercy on the part of the person pitied?

(2) To whom does it belong to pity?

(3) Whether mercy is a virtue?

(4) Whether it is the greatest of virtues?

Whether evil is properly the motive of mercy?

Objection 1: It would seem that, properly speaking, evil is not the motive of mercy. For, as shown above (Q[19], A[1]; [2590]FS, Q[79], A[1], ad 4; [2591]FP, Q[48] , A[6]), fault is an evil rather than punishment. Now fault provokes indignation rather than mercy. Therefore evil does not excite mercy.

Objection 2: Further, cruelty and harshness seem to excel other evils. Now the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 8) that “harshness does not call for pity but drives it away.” Therefore evil, as such, is not the motive of mercy.

Objection 3: Further, signs of evils are not true evils. But signs of evils excite one to mercy, as the Philosopher states (Rhet. ii, 8). Therefore evil, properly speaking, is not an incentive to mercy.

On the contrary, Damascene says (De Fide Orth. ii, 2) that mercy is a kind of sorrow. Now evil is the motive of sorrow. Therefore it is the motive of mercy.

I answer that, As Augustine says (De Civ. Dei ix, 5), mercy is heartfelt sympathy for another’s distress, impelling us to succor him if we can. For mercy takes its name “misericordia” from denoting a man’s compassionate heart [miserum cor] for another’s unhappiness. Now unhappiness is opposed to happiness: and it is essential to beatitude or happiness that one should obtain what one wishes; for, according to Augustine (De Trin. xiii, 5), “happy is he who has whatever he desires, and desires nothing amiss.” Hence, on the other hand, it belongs to unhappiness that a man should suffer what he wishes not.

Now a man wishes a thing in three ways: first, by his natural appetite; thus all men naturally wish to be and to live: secondly, a man wishes a thing from deliberate choice: thirdly, a man wishes a thing, not in itself, but in its cause, thus, if a man wishes to eat what is bad for him, we say that, in a way, he wishes to be ill.

Accordingly the motive of “mercy,” being something pertaining to “misery,” is, in the first way, anything contrary to the will’s natural appetite, namely corruptive or distressing evils, the contrary of which man desires naturally, wherefore the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 8) that “pity is sorrow for a visible evil, whether corruptive or distressing.” Secondly, such like evils are yet more provocative of pity if they are contrary to deliberate choice, wherefore the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 8) that evil excites our pity “when it is the result of an accident, as when something turns out ill, whereas we hoped well of it.” Thirdly, they cause yet greater pity, if they are entirely contrary to the will, as when evil befalls a man who has always striven to do well: wherefore the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 8) that “we pity most the distress of one who suffers undeservedly.”

Reply to Objection 1: It is essential to fault that it be voluntary; and in this respect it deserves punishment rather than mercy. Since, however, fault may be, in a way, a punishment, through having something connected with it that is against the sinner’s will, it may, in this respect, call for mercy. It is in this sense that we pity and commiserate sinners. Thus Gregory says in a homily (Hom. in Evang. xxxiv) that “true godliness is not disdainful but compassionate,” and again it is written (Mat. 9:36) that Jesus “seeing the multitudes, had compassion on them: because they were distressed, and lying like sheep that have no shepherd.”

Reply to Objection 2: Since pity is sympathy for another’s distress, it is directed, properly speaking, towards another, and not to oneself, except figuratively, like justice, according as a man is considered to have various parts (Ethic. v, 11). Thus it is written (Ecclus. 30:24): “Have pity on thy own soul, pleasing God” [*Cf.[2592] Q[106], A[3], ad 1].

Accordingly just as, properly speaking, a man does not pity himself, but suffers in himself, as when we suffer cruel treatment in ourselves, so too, in the case of those who are so closely united to us, as to be part of ourselves, such as our children or our parents, we do not pity their distress, but suffer as for our own sores; in which sense the Philosopher says that “harshness drives pity away.”

Reply to Objection 3: Just as pleasure results from hope and memory of good things, so does sorrow arise from the prospect or the recollection of evil things; though not so keenly as when they are present to the senses. Hence the signs of evil move us to pity, in so far as they represent as present, the evil that excites our pity.

Whether the reason for taking pity is a defect in the person who pities?

Objection 1: It would seem that the reason for taking pity is not a defect in the person who takes pity. For it is proper to God to be merciful, wherefore it is written (Ps. 144:9): “His tender mercies are over all His works.” But there is no defect in God. Therefore a defect cannot be the reason for taking pity.

Objection 2: Further, if a defect is the reason for taking pity, those in whom there is most defect, must needs take most pity. But this is false: for the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 8) that “those who are in a desperate state are pitiless.” Therefore it seems that the reason for taking pity is not a defect in the person who pities.

Objection 3: Further, to be treated with contempt is to be defective. But the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 8) that “those who are disposed to contumely are pitiless.” Therefore the reason for taking pity, is not a defect in the person who pities.

On the contrary, Pity is a kind of sorrow. But a defect is the reason of sorrow, wherefore those who are in bad health give way to sorrow more easily, as we shall say further on ([2593]Q[35], A[1], ad 2). Therefore the reason why one takes pity is a defect in oneself.

I answer that, Since pity is grief for another’s distress, as stated above [2594](A[1]), from the very fact that a person takes pity on anyone, it follows that another’s distress grieves him. And since sorrow or grief is about one’s own ills, one grieves or sorrows for another’s distress, in so far as one looks upon another’s distress as one’s own.

Now this happens in two ways: first, through union of the affections, which is the effect of love. For, since he who loves another looks upon his friend as another self, he counts his friend’s hurt as his own, so that he grieves for his friend’s hurt as though he were hurt himself. Hence the Philosopher (Ethic. ix, 4) reckons “grieving with one’s friend” as being one of the signs of friendship, and the Apostle says (Rom. 12:15): “Rejoice with them that rejoice, weep with them that weep.”

Secondly, it happens through real union, for instance when another’s evil comes near to us, so as to pass to us from him. Hence the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 8) that men pity such as are akin to them, and the like, because it makes them realize that the same may happen to themselves. This also explains why the old and the wise who consider that they may fall upon evil times, as also feeble and timorous persons, are more inclined to pity: whereas those who deem themselves happy, and so far powerful as to think themselves in no danger of suffering any hurt, are not so inclined to pity.

Accordingly a defect is always the reason for taking pity, either because one looks upon another’s defect as one’s own, through being united to him by love, or on account of the possibility of suffering in the same way.

Reply to Objection 1: God takes pity on us through love alone, in as much as He loves us as belonging to Him.

Reply to Objection 2: Those who are already in infinite distress, do not fear to suffer more, wherefore they are without pity. In like manner this applies to those also who are in great fear, for they are so intent on their own passion, that they pay no attention to the suffering of others.

Reply to Objection 3: Those who are disposed to contumely, whether through having been contemned, or because they wish to contemn others, are incited to anger and daring, which are manly passions and arouse the human spirit to attempt difficult things. Hence they make a man think that he is going to suffer something in the future, so that while they are disposed in that way they are pitiless, according to Prov. 27:4: “Anger hath no mercy, nor fury when it breaketh forth.” For the same reason the proud are without pity, because they despise others, and think them wicked, so that they account them as suffering deservedly whatever they suffer. Hence Gregory says (Hom. in Evang. xxxiv) that “false godliness,” i.e. of the proud, “is not compassionate but disdainful.”

Whether mercy is a virtue?

Objection 1: It would seem that mercy is not a virtue. For the chief part of virtue is choice as the Philosopher states (Ethic. ii, 5). Now choice is “the desire of what has been already counselled” (Ethic. iii, 2). Therefore whatever hinders counsel cannot be called a virtue. But mercy hinders counsel, according to the saying of Sallust (Catilin.): “All those that take counsel about matters of doubt, should be free from . . . anger . . . and mercy, because the mind does not easily see aright, when these things stand in the way.” Therefore mercy is not a virtue.

Objection 2: Further, nothing contrary to virtue is praiseworthy. But nemesis is contrary to mercy, as the Philosopher states (Rhet. ii, 9), and yet it is a praiseworthy passion (Rhet. ii, 9). Therefore mercy is not a virtue.

Objection 3: Further, joy and peace are not special virtues, because they result from charity, as stated above ([2595]Q[28], A[4];[2596] Q[29], A[4]). Now mercy, also, results from charity; for it is out of charity that we weep with them that weep, as we rejoice with them that rejoice. Therefore mercy is not a special virtue.

Objection 4: Further, since mercy belongs to the appetitive power, it is not an intellectual virtue, and, since it has not God for its object, neither is it a theological virtue. Moreover it is not a moral virtue, because neither is it about operations, for this belongs to justice; nor is it about passions, since it is not reduced to one of the twelve means mentioned by the Philosopher (Ethic. ii, 7). Therefore mercy is not a virtue.

On the contrary, Augustine says (De Civ. Dei ix, 5): “Cicero in praising Caesar expresses himself much better and in a fashion at once more humane and more in accordance with religious feeling, when he says: ‘Of all thy virtues none is more marvelous or more graceful than thy mercy.’” Therefore mercy is a virtue.

I answer that, Mercy signifies grief for another’s distress. Now this grief may denote, in one way, a movement of the sensitive appetite, in which case mercy is not a virtue but a passion; whereas, in another way, it may denote a movement of the intellective appetite, in as much as one person’s evil is displeasing to another. This movement may be ruled in accordance with reason, and in accordance with this movement regulated by reason, the movement of the lower appetite may be regulated. Hence Augustine says (De Civ. Dei ix, 5) that “this movement of the mind” (viz. mercy) “obeys the reason, when mercy is vouchsafed in such a way that justice is safeguarded, whether we give to the needy or forgive the repentant.” And since it is essential to human virtue that the movements of the soul should be regulated by reason, as was shown above ([2597]FS, Q[59], AA[4],5), it follows that mercy is a virtue.

Reply to Objection 1: The words of Sallust are to be understood as applying to the mercy which is a passion unregulated by reason: for thus it impedes the counselling of reason, by making it wander from justice.

Reply to Objection 2: The Philosopher is speaking there of pity and nemesis, considered, both of them, as passions. They are contrary to one another on the part of their respective estimation of another’s evils, for which pity grieves, in so far as it esteems someone to suffer undeservedly, whereas nemesis rejoices, in so far as it esteems someone to suffer deservedly, and grieves, if things go well with the undeserving: “both of these are praiseworthy and come from the same disposition of character” (Rhet. ii, 9). Properly speaking, however, it is envy which is opposed to pity, as we shall state further on ([2598]Q[36], A[3]).

Reply to Objection 3: Joy and peace add nothing to the aspect of good which is the object of charity, wherefore they do not require any other virtue besides charity. But mercy regards a certain special aspect, namely the misery of the person pitied.

Reply to Objection 4: Mercy, considered as a virtue, is a moral virtue having relation to the passions, and it is reduced to the mean called nemesis, because “they both proceed from the same character” (Rhet. ii, 9). Now the Philosopher proposes these means not as virtues, but as passions, because, even as passions, they are praiseworthy. Yet nothing prevents them from proceeding from some elective habit, in which case they assume the character of a virtue.

Whether mercy is the greatest of the virtues?

Objection 1: It would seem that mercy is the greatest of the virtues. For the worship of God seems a most virtuous act. But mercy is preferred before the worship of God, according to Osee 6:6 and Mat. 12:7: “I have desired mercy and not sacrifice.” Therefore mercy is the greatest virtue.

Objection 2: Further, on the words of 1 Tim. 4:8: “Godliness is profitable to all things,” a gloss says: “The sum total of a Christian’s rule of life consists in mercy and godliness.” Now the Christian rule of life embraces every virtue. Therefore the sum total of all virtues is contained in mercy.

Objection 3: Further, “Virtue is that which makes its subject good,” according to the Philosopher. Therefore the more a virtue makes a man like God, the better is that virtue: since man is the better for being more like God. Now this is chiefly the result of mercy, since of God is it said (Ps. 144:9) that “His tender mercies are over all His works,” and (Lk. 6:36) Our Lord said: “Be ye . . . merciful, as your Father also is merciful.” Therefore mercy is the greatest of virtues.

On the contrary, The Apostle after saying (Col. 3:12): “Put ye on . . . as the elect of God . . . the bowels of mercy,” etc., adds (Col. 3:14): “Above all things have charity.” Therefore mercy is not the greatest of virtues.

I answer that, A virtue may take precedence of others in two ways: first, in itself; secondly, in comparison with its subject. In itself, mercy takes precedence of other virtues, for it belongs to mercy to be bountiful to others, and, what is more, to succor others in their wants, which pertains chiefly to one who stands above. Hence mercy is accounted as being proper to God: and therein His omnipotence is declared to be chiefly manifested [*Collect, Tenth Sunday after Pentecost].

On the other hand, with regard to its subject, mercy is not the greatest virtue, unless that subject be greater than all others, surpassed by none and excelling all: since for him that has anyone above him it is better to be united to that which is above than to supply the defect of that which is beneath. [*”The quality of mercy is not strained./’ Tis mightiest in the mightiest: it becomes/The throned monarch better than his crown.” Merchant of Venice, Act IV, Scene i.]. Hence, as regards man, who has God above him, charity which unites him to God, is greater than mercy, whereby he supplies the defects of his neighbor. But of all the virtues which relate to our neighbor, mercy is the greatest, even as its act surpasses all others, since it belongs to one who is higher and better to supply the defect of another, in so far as the latter is deficient.

Reply to Objection 1: We worship God by external sacrifices and gifts, not for His own profit, but for that of ourselves and our neighbor. For He needs not our sacrifices, but wishes them to be offered to Him, in order to arouse our devotion and to profit our neighbor. Hence mercy, whereby we supply others’ defects is a sacrifice more acceptable to Him, as conducing more directly to our neighbor’s well-being, according to Heb. 13:16: “Do not forget to do good and to impart, for by such sacrifices God’s favor is obtained.”

Reply to Objection 2: The sum total of the Christian religion consists in mercy, as regards external works: but the inward love of charity, whereby we are united to God preponderates over both love and mercy for our neighbor.

Reply to Objection 3: Charity likens us to God by uniting us to Him in the bond of love: wherefore it surpasses mercy, which likens us to God as regards similarity of works.

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running