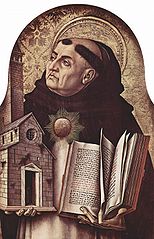

The Summa Theologica by Saint Thomas Aquinas

OF GOODNESS IN GENERAL (SIX ARTICLES)

We next consider goodness: First, goodness in general. Secondly, the goodness of God.

Under the first head there are six points of inquiry:

(1) Whether goodness and being are the same really?

(2) Granted that they differ only in idea, which is prior in thought?

(3) Granted that being is prior, whether every being is good?

(4) To what cause should goodness be reduced?

(5) Whether goodness consists in mode, species, and order?

(6) Whether goodness is divided into the virtuous, the useful, and the pleasant?

Whether goodness differs really from being?

Objection 1: It seems that goodness differs really from being. For Boethius says (De Hebdom.): “I perceive that in nature the fact that things are good is one thing: that they are is another.” Therefore goodness and being really differ.

Objection 2: Further, nothing can be its own form. “But that is called good which has the form of being,” according to the commentary on De Causis. Therefore goodness differs really from being.

Objection 3: Further, goodness can be more or less. But being cannot be more or less. Therefore goodness differs really from being.

On the contrary, Augustine says (De Doctr. Christ. i, 42) that, “inasmuch as we exist we are good.”

I answer that, Goodness and being are really the same, and differ only in idea; which is clear from the following argument. The essence of goodness consists in this, that it is in some way desirable. Hence the Philosopher says (Ethic. i): “Goodness is what all desire.” Now it is clear that a thing is desirable only in so far as it is perfect; for all desire their own perfection. But everything is perfect so far as it is actual. Therefore it is clear that a thing is perfect so far as it exists; for it is existence that makes all things actual, as is clear from the foregoing ([22]Q[3], A[4]; [23]Q[4], A[1]). Hence it is clear that goodness and being are the same really. But goodness presents the aspect of desirableness, which being does not present.

Reply to Objection 1: Although goodness and being are the same really, nevertheless since they differ in thought, they are not predicated of a thing absolutely in the same way. Since being properly signifies that something actually is, and actuality properly correlates to potentiality; a thing is, in consequence, said simply to have being, accordingly as it is primarily distinguished from that which is only in potentiality; and this is precisely each thing’s substantial being. Hence by its substantial being, everything is said to have being simply; but by any further actuality it is said to have being relatively. Thus to be white implies relative being, for to be white does not take a thing out of simply potential being; because only a thing that actually has being can receive this mode of being. But goodness signifies perfection which is desirable; and consequently of ultimate perfection. Hence that which has ultimate perfection is said to be simply good; but that which has not the ultimate perfection it ought to have (although, in so far as it is at all actual, it has some perfection), is not said to be perfect simply nor good simply, but only relatively. In this way, therefore, viewed in its primal (i.e. substantial) being a thing is said to be simply, and to be good relatively (i.e. in so far as it has being) but viewed in its complete actuality, a thing is said to be relatively, and to be good simply. Hence the saying of Boethius (De Hebrom.), “I perceive that in nature the fact that things are good is one thing; that they are is another,” is to be referred to a thing’s goodness simply, and having being simply. Because, regarded in its primal actuality, a thing simply exists; and regarded in its complete actuality, it is good simply—in such sort that even in its primal actuality, it is in some sort good, and even in its complete actuality, it in some sort has being.

Reply to Objection 2: Goodness is a form so far as absolute goodness signifies complete actuality.

Reply to Objection 3: Again, goodness is spoken of as more or less according to a thing’s superadded actuality, for example, as to knowledge or virtue.

Whether goodness is prior in idea to being?

Objection 1: It seems that goodness is prior in idea to being. For names are arranged according to the arrangement of the things signified by the names. But Dionysius (Div. Nom. iii) assigned the first place, amongst the other names of God, to His goodness rather than to His being. Therefore in idea goodness is prior to being.

Objection 2: Further, that which is the more extensive is prior in idea. But goodness is more extensive than being, because, as Dionysius notes (Div. Nom. v), “goodness extends to things both existing and non-existing; whereas existence extends to existing things alone.” Therefore goodness is in idea prior to being.

Objection 3: Further, what is the more universal is prior in idea. But goodness seems to be more universal than being, since goodness has the aspect of desirable; whereas to some non-existence is desirable; for it is said of Judas: “It were better for him, if that man had not been born” (Mat. 26:24). Therefore in idea goodness is prior to being.

Objection 4: Further, not only is existence desirable, but life, knowledge, and many other things besides. Thus it seems that existence is a particular appetible, and goodness a universal appetible. Therefore, absolutely, goodness is prior in idea to being.

On the contrary, It is said by Aristotle (De Causis) that “the first of created things is being.”

I answer that, In idea being is prior to goodness. For the meaning signified by the name of a thing is that which the mind conceives of the thing and intends by the word that stands for it. Therefore, that is prior in idea, which is first conceived by the intellect. Now the first thing conceived by the intellect is being; because everything is knowable only inasmuch as it is in actuality. Hence, being is the proper object of the intellect, and is primarily intelligible; as sound is that which is primarily audible. Therefore in idea being is prior to goodness.

Reply to Objection 1: Dionysius discusses the Divine Names (Div. Nom. i, iii) as implying some causal relation in God; for we name God, as he says, from creatures, as a cause from its effects. But goodness, since it has the aspect of desirable, implies the idea of a final cause, the causality of which is first among causes, since an agent does not act except for some end; and by an agent matter is moved to its form. Hence the end is called the cause of causes. Thus goodness, as a cause, is prior to being, as is the end to the form. Therefore among the names signifying the divine causality, goodness precedes being. Again, according to the Platonists, who, through not distinguishing primary matter from privation, said that matter was non-being, goodness is more extensively participated than being; for primary matter participates in goodness as tending to it, for all seek their like; but it does not participate in being, since it is presumed to be non-being. Therefore Dionysius says that “goodness extends to non-existence” (Div. Nom. v).

Reply to Objection 2: The same solution is applied to this objection. Or it may be said that goodness extends to existing and non-existing things, not so far as it can be predicated of them, but so far as it can cause them—if, indeed, by non-existence we understand not simply those things which do not exist, but those which are potential, and not actual. For goodness has the aspect of the end, in which not only actual things find their completion, but also towards which tend even those things which are not actual, but merely potential. Now being implies the habitude of a formal cause only, either inherent or exemplar; and its causality does not extend save to those things which are actual.

Reply to Objection 3: Non-being is desirable, not of itself, but only relatively—i.e. inasmuch as the removal of an evil, which can only be removed by non-being, is desirable. Now the removal of an evil cannot be desirable, except so far as this evil deprives a thing of some being. Therefore being is desirable of itself; and non-being only relatively, inasmuch as one seeks some mode of being of which one cannot bear to be deprived; thus even non-being can be spoken of as relatively good.

Reply to Objection 4: Life, wisdom, and the like, are desirable only so far as they are actual. Hence, in each one of them some sort of being is desired. And thus nothing can be desired except being; and consequently nothing is good except being.

Whether every being is good?

Objection 1: It seems that not every being is good. For goodness is something superadded to being, as is clear from A[1]. But whatever is added to being limits it; as substance, quantity, quality, etc. Therefore goodness limits being. Therefore not every being is good.

Objection 2: Further, no evil is good: “Woe to you that call evil good and good evil” (Is. 5:20). But some things are called evil. Therefore not every being is good.

Objection 3: Further, goodness implies desirability. Now primary matter does not imply desirability, but rather that which desires. Therefore primary matter does not contain the formality of goodness. Therefore not every being is good.

Objection 4: Further, the Philosopher notes (Metaph. iii) that “in mathematics goodness does not exist.” But mathematics are entities; otherwise there would be no science of mathematics. Therefore not every being is good.

On the contrary, Every being that is not God is God’s creature. Now every creature of God is good (1 Tim. 4:4): and God is the greatest good. Therefore every being is good.

I answer that, Every being, as being, is good. For all being, as being, has actuality and is in some way perfect; since every act implies some sort of perfection; and perfection implies desirability and goodness, as is clear from A[1]. Hence it follows that every being as such is good.

Reply to Objection 1: Substance, quantity, quality, and everything included in them, limit being by applying it to some essence or nature. Now in this sense, goodness does not add anything to being beyond the aspect of desirability and perfection, which is also proper to being, whatever kind of nature it may be. Hence goodness does not limit being.

Reply to Objection 2: No being can be spoken of as evil, formally as being, but only so far as it lacks being. Thus a man is said to be evil, because he lacks some virtue; and an eye is said to be evil, because it lacks the power to see well.

Reply to Objection 3: As primary matter has only potential being, so it is only potentially good. Although, according to the Platonists, primary matter may be said to be a non-being on account of the privation attaching to it, nevertheless, it does participate to a certain extent in goodness, viz. by its relation to, or aptitude for, goodness. Consequently, to be desirable is not its property, but to desire.

Reply to Objection 4: Mathematical entities do not subsist as realities; because they would be in some sort good if they subsisted; but they have only logical existence, inasmuch as they are abstracted from motion and matter; thus they cannot have the aspect of an end, which itself has the aspect of moving another. Nor is it repugnant that there should be in some logical entity neither goodness nor form of goodness; since the idea of being is prior to the idea of goodness, as was said in the preceding article.

Whether goodness has the aspect of a final cause?

Objection 1: It seems that goodness has not the aspect of a final cause, but rather of the other causes. For, as Dionysius says (Div. Nom. iv), “Goodness is praised as beauty.” But beauty has the aspect of a formal cause. Therefore goodness has the aspect of a formal cause.

Objection 2: Further, goodness is self-diffusive; for Dionysius says (Div. Nom. iv) that goodness is that whereby all things subsist, and are. But to be self-giving implies the aspect of an efficient cause. Therefore goodness has the aspect of an efficient cause.

Objection 3: Further, Augustine says (De Doctr. Christ. i, 31) that “we exist because God is good.” But we owe our existence to God as the efficient cause. Therefore goodness implies the aspect of an efficient cause.

On the contrary, The Philosopher says (Phys. ii) that “that is to be considered as the end and the good of other things, for the sake of which something is.” Therefore goodness has the aspect of a final cause.

I answer that, Since goodness is that which all things desire, and since this has the aspect of an end, it is clear that goodness implies the aspect of an end. Nevertheless, the idea of goodness presupposes the idea of an efficient cause, and also of a formal cause. For we see that what is first in causing, is last in the thing caused. Fire, e.g. heats first of all before it reproduces the form of fire; though the heat in the fire follows from its substantial form. Now in causing, goodness and the end come first, both of which move the agent to act; secondly, the action of the agent moving to the form; thirdly, comes the form. Hence in that which is caused the converse ought to take place, so that there should be first, the form whereby it is a being; secondly, we consider in it its effective power, whereby it is perfect in being, for a thing is perfect when it can reproduce its like, as the Philosopher says (Meteor. iv); thirdly, there follows the formality of goodness which is the basic principle of its perfection.

Reply to Objection 1: Beauty and goodness in a thing are identical fundamentally; for they are based upon the same thing, namely, the form; and consequently goodness is praised as beauty. But they differ logically, for goodness properly relates to the appetite (goodness being what all things desire); and therefore it has the aspect of an end (the appetite being a kind of movement towards a thing). On the other hand, beauty relates to the cognitive faculty; for beautiful things are those which please when seen. Hence beauty consists in due proportion; for the senses delight in things duly proportioned, as in what is after their own kind—because even sense is a sort of reason, just as is every cognitive faculty. Now since knowledge is by assimilation, and similarity relates to form, beauty properly belongs to the nature of a formal cause.

Reply to Objection 2: Goodness is described as self-diffusive in the sense that an end is said to move.

Reply to Objection 3: He who has a will is said to be good, so far as he has a good will; because it is by our will that we employ whatever powers we may have. Hence a man is said to be good, not by his good understanding; but by his good will. Now the will relates to the end as to its proper object. Thus the saying, “we exist because God is good” has reference to the final cause.

Whether the essence of goodness consists in mode, species and order?

Objection 1: It seems that the essence of goodness does not consist in mode, species and order. For goodness and being differ logically. But mode, species and order seem to belong to the nature of being, for it is written: “Thou hast ordered all things in measure, and number, and weight” (Wis. 11:21). And to these three can be reduced species, mode and order, as Augustine says (Gen. ad lit. iv, 3): “Measure fixes the mode of everything, number gives it its species, and weight gives it rest and stability.” Therefore the essence of goodness does not consist in mode, species and order.

Objection 2: Further, mode, species and order are themselves good. Therefore if the essence of goodness consists in mode, species and order, then every mode must have its own mode, species and order. The same would be the case with species and order in endless succession.

Objection 3: Further, evil is the privation of mode, species and order. But evil is not the total absence of goodness. Therefore the essence of goodness does not consist in mode, species and order.

Objection 4: Further, that wherein consists the essence of goodness cannot be spoken of as evil. Yet we can speak of an evil mode, species and order. Therefore the essence of goodness does not consist in mode, species and order.

Objection 5: Further, mode, species and order are caused by weight, number and measure, as appears from the quotation from Augustine. But not every good thing has weight, number and measure; for Ambrose says (Hexam. i, 9): “It is of the nature of light not to have been created in number, weight and measure.” Therefore the essence of goodness does not consist in mode, species and order.

On the contrary, Augustine says (De Nat. Boni. iii): “These three—mode, species and order—as common good things, are in everything God has made; thus, where these three abound the things are very good; where they are less, the things are less good; where they do not exist at all, there can be nothing good.” But this would not be unless the essence of goodness consisted in them. Therefore the essence of goodness consists in mode, species and order.

I answer that, Everything is said to be good so far as it is perfect; for in that way only is it desirable (as shown above [24]AA[1],3). Now a thing is said to be perfect if it lacks nothing according to the mode of its perfection. But since everything is what it is by its form (and since the form presupposes certain things, and from the form certain things necessarily follow), in order for a thing to be perfect and good it must have a form, together with all that precedes and follows upon that form. Now the form presupposes determination or commensuration of its principles, whether material or efficient, and this is signified by the mode: hence it is said that the measure marks the mode. But the form itself is signified by the species; for everything is placed in its species by its form. Hence the number is said to give the species, for definitions signifying species are like numbers, according to the Philosopher (Metaph. x); for as a unit added to, or taken from a number, changes its species, so a difference added to, or taken from a definition, changes its species. Further, upon the form follows an inclination to the end, or to an action, or something of the sort; for everything, in so far as it is in act, acts and tends towards that which is in accordance with its form; and this belongs to weight and order. Hence the essence of goodness, so far as it consists in perfection, consists also in mode, species and order.

Reply to Objection 1: These three only follow upon being, so far as it is perfect, and according to this perfection is it good.

Reply to Objection 2: Mode, species and order are said to be good, and to be beings, not as though they themselves were subsistences, but because it is through them that other things are both beings and good. Hence they have no need of other things whereby they are good: for they are spoken of as good, not as though formally constituted so by something else, but as formally constituting others good: thus whiteness is not said to be a being as though it were by anything else; but because, by it, something else has accidental being, as an object that is white.

Reply to Objection 3: Every being is due to some form. Hence, according to every being of a thing is its mode, species, order. Thus, a man has a mode, species and order as he is white, virtuous, learned and so on; according to everything predicated of him. But evil deprives a thing of some sort of being, as blindness deprives us of that being which is sight; yet it does not destroy every mode, species and order, but only such as follow upon the being of sight.

Reply to Objection 4: Augustine says (De Nat. Boni. xxiii), “Every mode, as mode, is good” (and the same can be said of species and order). “But an evil mode, species and order are so called as being less than they ought to be, or as not belonging to that which they ought to belong. Therefore they are called evil, because they are out of place and incongruous.”

Reply to Objection 5: The nature of light is spoken of as being without number, weight and measure, not absolutely, but in comparison with corporeal things, because the power of light extends to all corporeal things; inasmuch as it is an active quality of the first body that causes change, i.e. the heavens.

Whether goodness is rightly divided into the virtuous*, the useful and the pleasant? [*”Bonum honestum” is the virtuous good considered as fitting. (cf. SS, Q[141], A[3]; SS, Q[145])]

Objection 1: It seems that goodness is not rightly divided into the virtuous, the useful and the pleasant. For goodness is divided by the ten predicaments, as the Philosopher says (Ethic. i). But the virtuous, the useful and the pleasant can be found under one predicament. Therefore goodness is not rightly divided by them.

Objection 2: Further, every division is made by opposites. But these three do not seem to be opposites; for the virtuous is pleasing, and no wickedness is useful; whereas this ought to be the case if the division were made by opposites, for then the virtuous and the useful would be opposed; and Tully speaks of this (De Offic. ii). Therefore this division is incorrect.

Objection 3: Further, where one thing is on account of another, there is only one thing. But the useful is not goodness, except so far as it is pleasing and virtuous. Therefore the useful ought not to divided against the pleasant and the virtuous.

On the contrary, Ambrose makes use of this division of goodness (De Offic. i, 9)

I answer that, This division properly concerns human goodness. But if we consider the nature of goodness from a higher and more universal point of view, we shall find that this division properly concerns goodness as such. For everything is good so far as it is desirable, and is a term of the movement of the appetite; the term of whose movement can be seen from a consideration of the movement of a natural body. Now the movement of a natural body is terminated by the end absolutely; and relatively by the means through which it comes to the end, where the movement ceases; so a thing is called a term of movement, so far as it terminates any part of that movement. Now the ultimate term of movement can be taken in two ways, either as the thing itself towards which it tends, e.g. a place or form; or a state of rest in that thing. Thus, in the movement of the appetite, the thing desired that terminates the movement of the appetite relatively, as a means by which something tends towards another, is called the useful; but that sought after as the last thing absolutely terminating the movement of the appetite, as a thing towards which for its own sake the appetite tends, is called the virtuous; for the virtuous is that which is desired for its own sake; but that which terminates the movement of the appetite in the form of rest in the thing desired, is called the pleasant.

Reply to Objection 1: Goodness, so far as it is identical with being, is divided by the ten predicaments. But this division belongs to it according to its proper formality.

Reply to Objection 2: This division is not by opposite things; but by opposite aspects. Now those things are called pleasing which have no other formality under which they are desirable except the pleasant, being sometimes hurtful and contrary to virtue. Whereas the useful applies to such as have nothing desirable in themselves, but are desired only as helpful to something further, as the taking of bitter medicine; while the virtuous is predicated of such as are desirable in themselves.

Reply to Objection 3: Goodness is not divided into these three as something univocal to be predicated equally of them all; but as something analogical to be predicated of them according to priority and posteriority. Hence it is predicated chiefly of the virtuous; then of the pleasant; and lastly of the useful.

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running